‘Wilhelm Furtwängler’ Review: Apostle of Inwardness WSJ 2018.8.3

BOOK

‘Wilhelm Furtwängler’ Review: Apostle of Inwardness

Furtwängler was no Nazi but was a tool of Hitler and Goebbels. His insistence on being ‘nonpolitical’ was naive—and yet also, it seems, sincere.

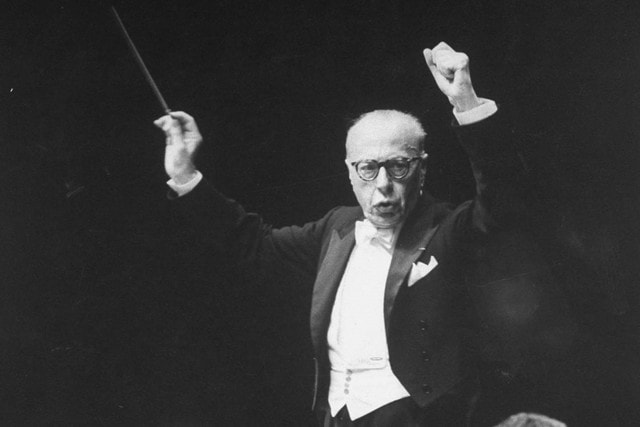

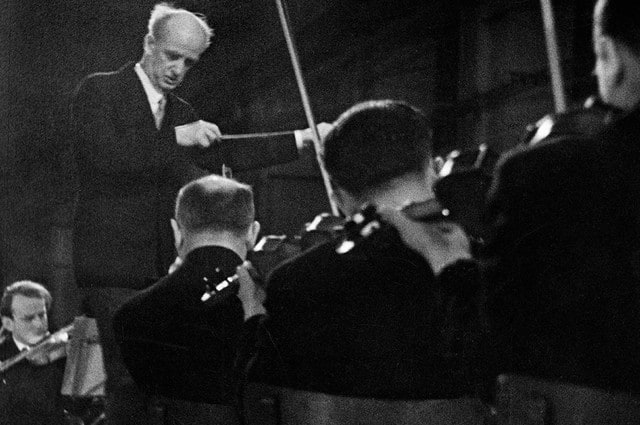

One of the most thrilling documents of symphonic music in performance—readily accessible on YouTube—is a clip of Wilhelm Furtwängler leading the Berlin Philharmonic in the closing five minutes of Brahms’s Symphony No. 4. Furtwängler is not commanding a performing army. Rather he is channeling a trembling state of heightened emotional awareness so irresistible as to obliterate, in the moment, all previous encounters with the music at hand. This experience is both empowering and—upon reflection—a little scary. And it occurred some three years after the implosion of Hitler’s Third Reich—a regime for which Furtwängler, though not exactly an advocate, was a potent cultural symbol.

In 20th-century classical music, the iconic embodiment of the fight for democratic freedoms was the Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, who fled Europe and galvanized opposition to Hitler and Mussolini. Furtwängler (1886-1954), who remained behind, was Toscanini’s iconic antipode, eschewing the objective clarity of Toscanini’s literalism in favor of Teutonic ideals of lofty subjective spirituality.

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical

By Roger Allen

Boydell, 286 pages, $39.95

https://www.amazon.co.jp/gp/product/178327283X/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1_1_1?smid=AN1VRQENFRJN5&psc=1

Furtwängler was inaccurately denounced in America as a Nazi. His de-Nazification proceedings were misreported in the New York Times. Afterward, he was prevented by a blacklist from conducting the Chicago Symphony or the Metropolitan Opera, both of which wanted him.

Furtwängler was no Nazi. Behind the scenes, he helped Jewish musicians. Before the war ended, he fled Germany for Switzerland. Even so, his insistence on being “nonpolitical” was naive and self-deluded. As a tool of Hitler and Goebbels, he potently abetted the German war effort. In effect, he lent his prestige to the Third Reich whenever he performed, whether in Berlin or abroad. He was also famously photographed shaking hands with Goebbels from the stage.

In “Wilhelm Furtwängler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical,” Roger Allen, a fellow at St. Peter’s College, Oxford, doesn’t dwell on any of this. Rather he undertakes a deeper inquiry and asks: Did Furtwängler espouse a characteristically German cultural-philosophical mind-set that in effect embedded Hitler? He answers yes. But the answer is glib.

Mr. Allen’s method is to cull a mountain of Furtwängler writings. That Furtwängler at all times embodied what Thomas Mann in 1945 called “the German-Romantic counter-revolution in intellectual history” is documented beyond question. He was an apostle of Germanic inwardness. He endorsed the philosophical precepts of Hegel and the musical analyses of Heinrich Schenker, for whom German composers mattered most. All this, Mr. Allen shows, propagated notions of “organic” authenticity recapitulated by Nazi ideologues.

Furtwängler’s writings as sampled here (others are better) are repetitious—and so, alas, is Mr. Allen’s commentary. The tensions and paradoxes complicating Furtwängler’s devil’s pact, his surrender to communal ecstasies ennobling or perilous, are reduced to simplistic presumption. Furtwängler’s murky Germanic thinking remains murky and uncontextualized. One would never know, from Mr. Allen’s exegesis, that Hegel formulated a sophisticated “holistic” alternative to the Enlightenment philosophies undergirding Anglo-American understandings of free will. One would never suspect that Schenkerian analysis, extrapolating the fundamental harmonic subcurrents upon which Furtwängler’s art feasted, is today alive and well.

Here’s an example. Furtwängler writes: “Bruckner is one of the few geniuses . . . whose appointed task was to express the transcendental in human terms, to weave the power of God into the fabric of human life. Be it in struggles against demonic forces, or in music of blissful transfiguration, his whole mind and spirit were infused with thoughts of the divine.” Mr. Allen comments: “It is this idea, with its anti-intellectual subtext, which associates Furtwängler so strongly with aspects of Nazi ideology. . . . That Bruckner’s music represents the power of God at work in the fabric of human existence, can be seen as an extension of the Nazi . . . belief in God as a mystical creative power.” But many who revere Brucknerian “divine bliss” are neither anti-intellectual nor religiously inclined.

A much more compelling section of Mr. Allen’s narrative comes at the end, when he observes that Furtwängler blithely maintained his musical ideology after World War II, with no evident pause for reflection. One can agree that this says something unpleasant about the Furtwängler persona, suggesting a nearly atavistic truculence. But it is reductionist to analogize Furtwängler’s unrelenting postwar hostility to nontonal music to “the non-rational censure of ‘degenerate’ art by the Nazis.” Far more interesting is Furtwängler’s own argument that the nontonal music of Arnold Schoenberg and his followers lacks an “overview.” A calibrated long-range trajectory of musical thought was an essential ingredient of Furtwängler’s interpretive art. Absent the tension-and-release dynamic of tonal harmony, he had little to work with.

The political dangers inherent in German Romantic music are a familiar concern, beginning with Nietzsche’s skewerings of Wagner. The best writer on this topic remains Thomas Mann, who lived it. Here he is in “Reflections of a Non-Political Man” (1918): “Art will never be moral or virtuous in any political sense: and progress will never be able to put its trust in art. It has a fundamental tendency to unreliability and treachery; its . . . predilection for the ‘barbarism’ that begets beauty [is] indestructible; and although some may call this predilection . . . immoral to the point of endangering the world, yet it is an imperishable fact of life, and if one wanted to eradicate this aspect of art . . . then one might well have freed the world from a serious danger; but in the process one would almost certainly have freed it from art itself.”

With the coming of Hitler, Mann changed his tune and moved to California. The most impressive pages of Mr. Allen’s book come in an appendix: Mann’s lecture “Germany and the Germans,” delivered at the Library of Congress in 1945. Mann here becomes a proud American: “Everything else would have meant too narrow and specific an alienation of my existence. As an American I am a citizen of the world.”

It is pertinent to remember that seven years later, having witnessed the Cold War and the Red Scare, Mann deserted the U.S. for Switzerland; as early as 1951 he wrote to a friend: “I have no desire to rest my bones in this soulless soil to which I owe nothing, and which knows nothing of me.”

Wilhelm Furtwängler’s refusal to emigrate, however else construed, is not irrelevant here. He processed much differently the stresses that drove Thomas Mann into permanent exile.

—Mr. Horowitz is the author of “Understanding Toscanini,” among many other books.

Appeared in the August 4, 2018, print edition as 'Apostle of Inwardness.'