‘Wilhelm Furtwängler’ Review: Apostle of Inwardness WSJ 2018.8.3

BOOK

‘Wilhelm Furtwängler’ Review: Apostle of Inwardness

Furtwängler was no Nazi but was a tool of Hitler and Goebbels. His insistence on being ‘nonpolitical’ was naive—and yet also, it seems, sincere.

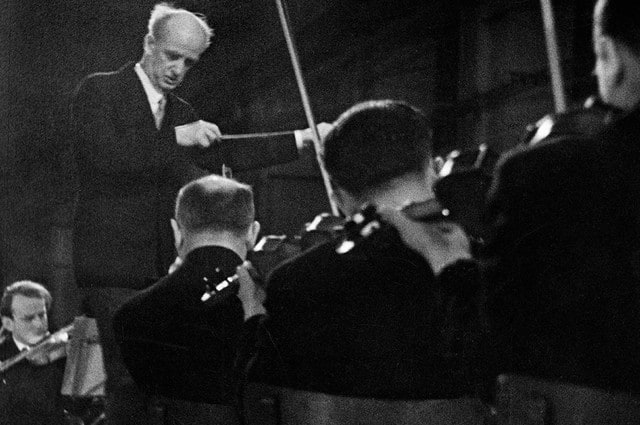

One of the most thrilling documents of symphonic music in performance—readily accessible on YouTube—is a clip of Wilhelm Furtwängler leading the Berlin Philharmonic in the closing five minutes of Brahms’s Symphony No. 4. Furtwängler is not commanding a performing army. Rather he is channeling a trembling state of heightened emotional awareness so irresistible as to obliterate, in the moment, all previous encounters with the music at hand. This experience is both empowering and—upon reflection—a little scary. And it occurred some three years after the implosion of Hitler’s Third Reich—a regime for which Furtwängler, though not exactly an advocate, was a potent cultural symbol.

In 20th-century classical music, the iconic embodiment of the fight for democratic freedoms was the Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, who fled Europe and galvanized opposition to Hitler and Mussolini. Furtwängler (1886-1954), who remained behind, was Toscanini’s iconic antipode, eschewing the objective clarity of Toscanini’s literalism in favor of Teutonic ideals of lofty subjective spirituality.

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical

By Roger Allen

Boydell, 286 pages, $39.95

https://www.amazon.co.jp/gp/product/178327283X/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1_1_1?smid=AN1VRQENFRJN5&psc=1

Furtwängler was inaccurately denounced in America as a Nazi. His de-Nazification proceedings were misreported in the New York Times. Afterward, he was prevented by a blacklist from conducting the Chicago Symphony or the Metropolitan Opera, both of which wanted him.

Furtwängler was no Nazi. Behind the scenes, he helped Jewish musicians. Before the war ended, he fled Germany for Switzerland. Even so, his insistence on being “nonpolitical” was naive and self-deluded. As a tool of Hitler and Goebbels, he potently abetted the German war effort. In effect, he lent his prestige to the Third Reich whenever he performed, whether in Berlin or abroad. He was also famously photographed shaking hands with Goebbels from the stage.

In “Wilhelm Furtwängler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical,” Roger Allen, a fellow at St. Peter’s College, Oxford, doesn’t dwell on any of this. Rather he undertakes a deeper inquiry and asks: Did Furtwängler espouse a characteristically German cultural-philosophical mind-set that in effect embedded Hitler? He answers yes. But the answer is glib.

Mr. Allen’s method is to cull a mountain of Furtwängler writings. That Furtwängler at all times embodied what Thomas Mann in 1945 called “the German-Romantic counter-revolution in intellectual history” is documented beyond question. He was an apostle of Germanic inwardness. He endorsed the philosophical precepts of Hegel and the musical analyses of Heinrich Schenker, for whom German composers mattered most. All this, Mr. Allen shows, propagated notions of “organic” authenticity recapitulated by Nazi ideologues.

Furtwängler’s writings as sampled here (others are better) are repetitious—and so, alas, is Mr. Allen’s commentary. The tensions and paradoxes complicating Furtwängler’s devil’s pact, his surrender to communal ecstasies ennobling or perilous, are reduced to simplistic presumption. Furtwängler’s murky Germanic thinking remains murky and uncontextualized. One would never know, from Mr. Allen’s exegesis, that Hegel formulated a sophisticated “holistic” alternative to the Enlightenment philosophies undergirding Anglo-American understandings of free will. One would never suspect that Schenkerian analysis, extrapolating the fundamental harmonic subcurrents upon which Furtwängler’s art feasted, is today alive and well.

Here’s an example. Furtwängler writes: “Bruckner is one of the few geniuses . . . whose appointed task was to express the transcendental in human terms, to weave the power of God into the fabric of human life. Be it in struggles against demonic forces, or in music of blissful transfiguration, his whole mind and spirit were infused with thoughts of the divine.” Mr. Allen comments: “It is this idea, with its anti-intellectual subtext, which associates Furtwängler so strongly with aspects of Nazi ideology. . . . That Bruckner’s music represents the power of God at work in the fabric of human existence, can be seen as an extension of the Nazi . . . belief in God as a mystical creative power.” But many who revere Brucknerian “divine bliss” are neither anti-intellectual nor religiously inclined.

A much more compelling section of Mr. Allen’s narrative comes at the end, when he observes that Furtwängler blithely maintained his musical ideology after World War II, with no evident pause for reflection. One can agree that this says something unpleasant about the Furtwängler persona, suggesting a nearly atavistic truculence. But it is reductionist to analogize Furtwängler’s unrelenting postwar hostility to nontonal music to “the non-rational censure of ‘degenerate’ art by the Nazis.” Far more interesting is Furtwängler’s own argument that the nontonal music of Arnold Schoenberg and his followers lacks an “overview.” A calibrated long-range trajectory of musical thought was an essential ingredient of Furtwängler’s interpretive art. Absent the tension-and-release dynamic of tonal harmony, he had little to work with.

The political dangers inherent in German Romantic music are a familiar concern, beginning with Nietzsche’s skewerings of Wagner. The best writer on this topic remains Thomas Mann, who lived it. Here he is in “Reflections of a Non-Political Man” (1918): “Art will never be moral or virtuous in any political sense: and progress will never be able to put its trust in art. It has a fundamental tendency to unreliability and treachery; its . . . predilection for the ‘barbarism’ that begets beauty [is] indestructible; and although some may call this predilection . . . immoral to the point of endangering the world, yet it is an imperishable fact of life, and if one wanted to eradicate this aspect of art . . . then one might well have freed the world from a serious danger; but in the process one would almost certainly have freed it from art itself.”

With the coming of Hitler, Mann changed his tune and moved to California. The most impressive pages of Mr. Allen’s book come in an appendix: Mann’s lecture “Germany and the Germans,” delivered at the Library of Congress in 1945. Mann here becomes a proud American: “Everything else would have meant too narrow and specific an alienation of my existence. As an American I am a citizen of the world.”

It is pertinent to remember that seven years later, having witnessed the Cold War and the Red Scare, Mann deserted the U.S. for Switzerland; as early as 1951 he wrote to a friend: “I have no desire to rest my bones in this soulless soil to which I owe nothing, and which knows nothing of me.”

Wilhelm Furtwängler’s refusal to emigrate, however else construed, is not irrelevant here. He processed much differently the stresses that drove Thomas Mann into permanent exile.

—Mr. Horowitz is the author of “Understanding Toscanini,” among many other books.

Appeared in the August 4, 2018, print edition as 'Apostle of Inwardness.'

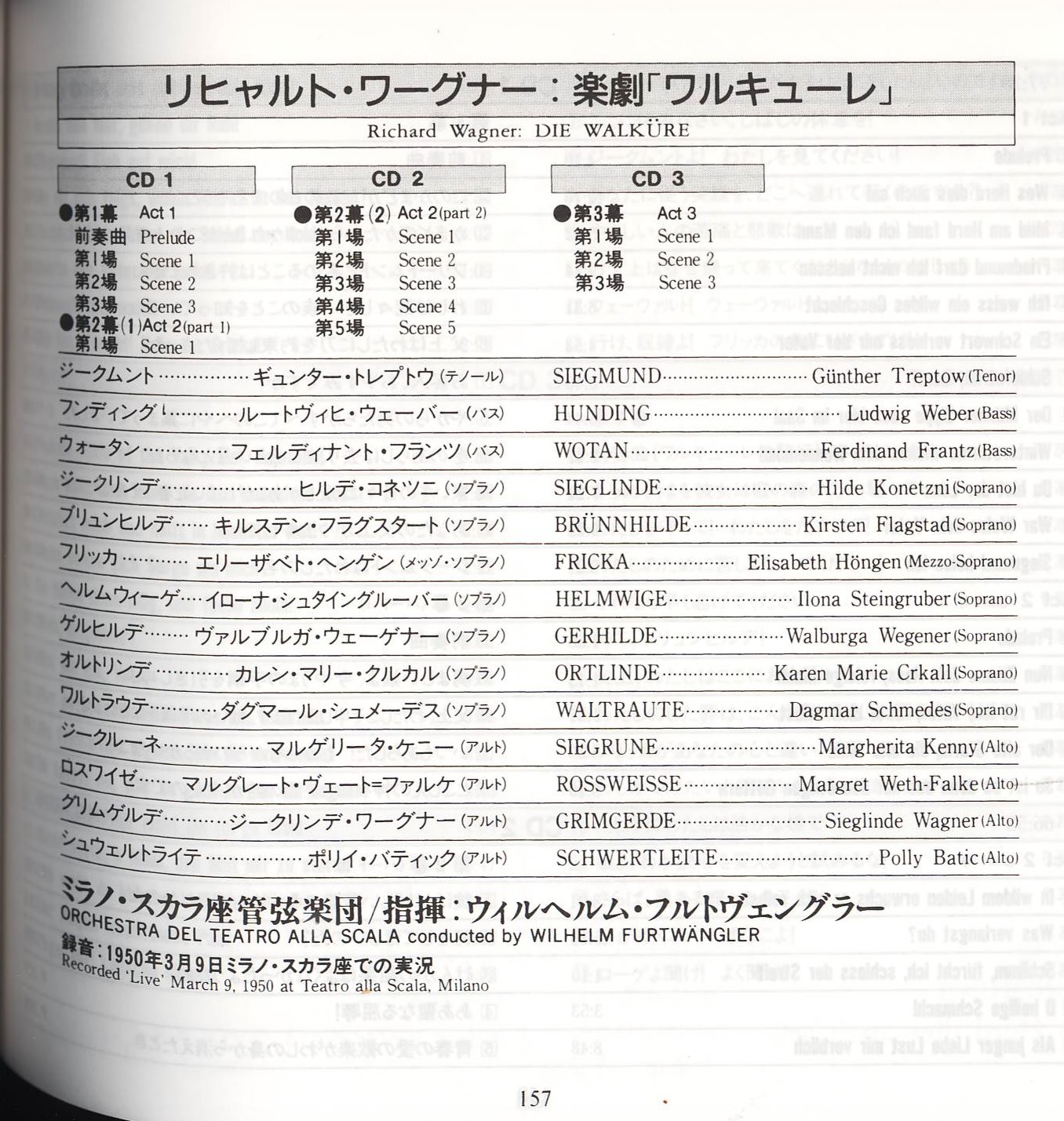

今年2016年11月にSACDハイブリッド盤がでたので購入。

例によって曲の途中でズタズタ切る編集ながら、CD盤とちょっと違っているところがありましたので、とりあえず全部比較することにしました。

ワルキューレが4枚から3枚に。ほかは同じです。

CD盤 SEVEN SEAS KICC 2231/44 発売日1992/11/21

SACDハイブリッド盤 SEVEN SEAS KKC 4072/84 発売日2016/11/23

*****************

【随時内容更新1】

ワルキューレ1幕を比べてみました。

・SACDでは、演奏前の登場拍手が収録されています。CDでは収録されていません。

・SACDでは、演奏後の拍手が収録されていません。CDでは収録されています。

・SACDでは1枚目に1幕全部と2幕頭少し入ってます。1幕が終わったところで拍手も何もなし。0.1秒も置かずほぼ連続演奏。編集ミスではないかと思えるぐらい続けざまに2幕に入る。(購入先に確認中2016/12/14)

・音質はSACDでも丸みは出てきてないのですが、キンキンがCDより疲れる。耳が疲れた。

*****************

【随時内容更新2】

購入先から回答あり(2016/12/26)

不良ではないが返品に応じる、とのこと。

何度かやりとりがあり(注)、最終的に、「不良ではない」が「返品に応じる」とのこと。

「不良ではない」というのは製造元の言。

「返品に応じる」というのは販売元の言。

(注)これの焦点は、拍手のカットの話ではなくて、ワルキューレ第1幕と第2幕頭のカッティングがつながっているのではないか、ということです。

結局、返品しました。以上

*****************

絵の順番は、楽劇別に CD→SACDハイブリッド です。

ラインの黄金CD

ラインの黄金SACDハイブリッド

ワルキューレCD

ワルキューレSACDハイブリッド

ジークフリートCD

ジークフリートSACDハイブリッド

神々の黄昏CD

神々の黄昏SACDハイブリッド

以上、

いつになったらまるごと収録の正規品だしてくれるんでしょうか。

フルトヴェングラーはベルリン・フィルとの時代に、ニューヨーク・フィルを3シーズン続けて振っています。

その演奏会、全プログラムを随分前にアップしました。OCNのブログサービス廃止に伴い、こちらサイトに引越ししましたが、うまく移行されておらず、今回少し整理してみました。

このデータはニューヨーク・フィルのパフォーマンス・ヒストリーのデータベースが出来る前のもので、最終的にはもう一度整理しなおすことになるかと思います。

1924-1925シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル83年目)

1925-1926シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル84年目)

1926-1927シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル85年目)

おわり

フルトヴェングラーは脂がのりきっていたときに、ニューヨーク・フィルの定期を3シーズン振った。

1924-1925シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル83年目)

1925-1926シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル84年目)

1926-1927シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル85年目)

3回目のシーズン1926-1927シーズンは下表に書いたような感じ。

2156回(1927.2.10)から2188回(1927.4.3)まで、33回全部振りきっている。

プログラムは最初の2シーズンと比べるとオーソドックス。

本領発揮という感じ。

2160回にミヤスコフスキーがあるのが興味深いが、何かの間違いではないかとさえ思える違和感だ。

ウィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー指揮

ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニック

CH:カーネギー・ホール

BAM:ブルックリン・アカデミー・オブ・ミュージック

--------------------------------------

2156th 1927/2/10 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シューマン チェロ協奏曲

チェロ、パブロ・カザルス

シュトラウス 英雄の生涯

--------------------------------------

2157th 1927/2/11 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2156th

--------------------------------------

2158th 1927/2/12 Sat 8:30 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン コリオラン、序曲

ブラームス ヴァイオリン協奏曲

ヴァイオリン、BERNARD OCKO

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第7番

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの第9回目

--------------------------------------

2159th 1927/2/13 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン 序曲、コリオラン

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第7番

チャイコフスキー ロメオとジュリエット

ベルリオーズ ラコッツィ行進曲

--------------------------------------

2160th 1927/2/17 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ベルリオーズ 序曲、ローマの謝肉祭

ミヤスコフスキー 交響曲第7番

(アメリカ初演)

ブラームス 交響曲第2番

--------------------------------------

2161st 1927/2/18 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2160th

--------------------------------------

2162nd 1927/2/20 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン エグモント、序曲

ブラームス ヴァイオリン協奏曲

ヴァイオリン、PAUL KOCHANSKI

シュトラウス 英雄の生涯

--------------------------------------

2163rd 1927/2/24 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

メンデルスゾーン 交響曲第3番

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

ヒンデミット オーケストラのための協奏曲

ワーグナー タンホイザー、序曲

--------------------------------------

2164th 1927/2/25 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2163rd

--------------------------------------

2165th 1927/2/27 Sun 3:15 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン コリオラン、序曲

ブラームス ヴァイオリン協奏曲

ヴァイオリン、PAUL KOCHANSKI

チャイコフスキー ロメオとジュリエット

ワーグナー タンホイザー、序曲

--------------------------------------

2166th 1927/3/1 Tue 8:30 PM .CH

オール・ワーグナー・プログラム

ローエングリン、前奏曲

ラインの黄金、ワルハラ

ラインの黄金、エルダ

ワルキューレ、終曲

トリスタン、前奏曲と愛の死

ワルキューレ、騎行

神々の黄昏、ワルトラウテ

マイスタージンガー、前奏曲

*ペンション・ファンド・コンサート

--------------------------------------

2167th 1927/3/3 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

バッハ ブランデンブルク協奏曲第3番

プロコフィエフ ヴァイオリン協奏曲,Op19

ヴァイオリン、ヨゼフ・シゲティ

ベートーヴェン レオノーレ序曲第2番

(アメリカ初演)

フランク 交響曲

--------------------------------------

2168th 1927/3/4 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2167th

--------------------------------------

2169th 1927/3/6 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブラームス 交響曲第2番

--------------------------------------

2170th 1927/3/7 Mon 8:15 PM アカデミー・オブ・ミュージック、フィラデルフィア

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブラームス 交響曲第2番

--------------------------------------

2171st 1927/3/8 Tue 4:30 PM ナショナル・シアター

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブラームス 交響曲第1番

--------------------------------------

2172nd 1927/3/9 Wed evening リリック・シアター、ボルティモア

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブラームス 交響曲第1番

--------------------------------------

2173rd 1927/3/10 Thur evening マジェスティック・シアター、ハリスバーグ

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブラームス 交響曲第1番

--------------------------------------

2174th 1927/3/11 Fri evening

ベートーヴェン コリオラン、序曲

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第7番

チャイコフスキー ロメオとジュリエット

ワーグナー タンホイザー、序曲

--------------------------------------

2175th 1927/3/12 Sat afternoon

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

シベリウス テンペスト、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブラームス 交響曲第1番

--------------------------------------

2176th 1927/3/13 Sun 3:00 PM

メトロポリタン・オペラ・ハウス

フランク 交響曲

チャイコフスキー ロメオとジュリエット

ベルリオーズ 序曲、ローマの謝肉祭

--------------------------------------

2177th 1927/3/17 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ブラウンフェルズ ドン・ファン

シュトラウス 死と変容

ブラームス ピアノ協奏曲第2番

ピアノ、OSSIP GAGBRILOWITSCH

--------------------------------------

2178th 1927/3/18 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2177th

--------------------------------------

2179th 1927/3/19 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

バッハ ブランデンブルク協奏曲第3番

ヒンデミット オーケストラのための協奏曲

チャイコフスキー 交響曲第4番

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの第10回目

--------------------------------------

2180th 1927/3/20 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

バッハ ブランデンブルク協奏曲第3番

シェリング ピアノとオーケストラの為の幻想的組曲

ピアノ、エルネスト・シェリング

チャイコフスキー 交響曲第4番

--------------------------------------

2181st 1927/3/24 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン・プログラム

大フーガ

ピアノ協奏曲,OP58

ピアノ、ワルター・ギーゼキング

交響曲第5番

--------------------------------------

2182nd 1927/3/25 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2181st

--------------------------------------

2183rd 1927/3/26 Sat 8:30 PM .CH

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ブルッフ コル・ニドライ

シュルツ ベルキュース

ドヴォルザーク ロンド

以上3曲チェロ、レオ・シュルツ

フランク 交響曲

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの第11回目

--------------------------------------

2184th 1927/3/27 Sun 3:15 PM .BAM

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

シェリング ピアノとオーケストラのための幻想的組曲

ピアノ、エルネスト・シェリング

フランク 交響曲

--------------------------------------

2185th 1927/3/31 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ブラームス ドイツ・レクイエム

ソプラノ、ELISABETH RETHBERG

バリトン、FRASER GANGE

CHORAL SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

--------------------------------------

2186th 1927/4/1 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2185th

--------------------------------------

2187th 1927/4/2 Sat 8:30 PM .CH

ブラウンフェルズ ドン・ファン

シュトラウス 詩と変容

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第5番

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの第12回目

--------------------------------------

2188th 1927/4/3 Sun 3:00 PM

メトロポリタン・オペラ・ハウス

ブラームス ドイツ・レクイエム

ソプラノ、LOUISE LERCH

バリトン、FRASER GANGE

CHORAL SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

--------------------------------------

フルトヴェングラーは脂がのりきっていたときに、ニューヨーク・フィルの定期を3シーズン振った。

1924-1925シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル83年目)

1925-1926シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル84年目)

1926-1927シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル85年目)

2回目のシーズン1925-1926シーズンは下表に書いたような感じ。

2051回(1926.2.11)から2082回(1926.4.2)まで、2057回目を除く、31回を振っている。

フィラデルフィア方面への演奏旅行も含め、約一ヵ月半の間、独占状態。

昔は交通手段が今ほど発達していないから、一度ある場所に落ち着いてしまうと、そこで長く演奏会に従事することになる。それにしても、ほぼ常任指揮者のような感じだ。

曲目も充実している。特に、2077th、2078thがすごい。今ならこのようなプログラムビルディングはありえない。また、最後の2回はエロイカで〆ている。

ウィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー指揮

ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニック

CH:カーネギー・ホール

BAM:ブルックリン・アカデミー・オブ・ミュージック

--------------------------------------

2051st 1926/2/11 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン エグモント序曲

モーツァルト アイネクライネ

ブラームス 交響曲第4番

ワーグナー マイスター前奏曲

--------------------------------------

2052nd 1926/2/12 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2051st

--------------------------------------

2053rd 1926/2/13 Sat 8:30 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン エグモント序曲

ヴァレンティーニ チェロとオーケストラの為の組曲

チェロ、ハンス・キンドラー

ブラームス 交響曲第4番

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの9回目

--------------------------------------

2054th 1926/2/14 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

ドヴォルザーク 新世界

ヴァレンティーニ チェロとオーケストラの為の組曲

チェロ、ハンス・キンドラー

ワーグナー マイスター前奏曲

--------------------------------------

2055th 1926/2/18 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ハイドン 交響曲第13番

シューマン ピアノ協奏曲

ピアノ、Guiomar Novaes

シュトラウス 家庭交響曲

--------------------------------------

2056th 1926/2/19 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2055th

--------------------------------------

2058th 1926/2/21 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

ウェーバー オベロン序曲

モーツァルト アイネクライネ

ブラームス 交響曲第4番

--------------------------------------

2059th 1926/2/23 Tue 8:30 PM ウォルドルフ・アストリア

モーツァルト アイネクライネ

シューベルト ロザムンデから

ドヴォルザーク スラブ舞曲

ブラームス ハンガリー舞曲(2曲)

シュトラウス 皇帝円舞曲

*軽音楽の夕べ

--------------------------------------

2060th 1926/2/25 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ベルリオーズ 海賊序曲

レスピーギ リュートの為の古い歌と舞曲、第2集

チャイコフスキー 悲愴

--------------------------------------

2061st 1926/2/26 Fri 8:30 PM .CH

同 2060th

--------------------------------------

2062nd 1926/2/28 Sun 3:15 PM .BAM

ハイドン 交響曲第13番

ベートーヴェン エグモント序曲

ブラームス ヴァイオリン協奏曲

ヴァイオリン、ヨゼフ・シゲティ

ワーグナー マイスター前奏曲

--------------------------------------

2063rd 1926/3/4 Thur 2:30 PM .CH

モーツァルト フィガロ序曲

シューマン 交響曲第1番

シュトラウス インテルメッツォから間奏曲とワルツ

ブラームス ハンガリー舞曲(3曲)

--------------------------------------

2064th 1926/3/5 Fri 8:15 PM .CH

同 2063rd

--------------------------------------

2065th 1926/3/7 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

ハイドン 交響曲第13番

メンデルスゾーン ヴァイオリン協奏曲

ヴァイオリン、Scipione Guidi

シュトラウス ティル

--------------------------------------

2066th 1926/3/8 Mon 8:15 PM .Academy of Music, PA

ブラームス 交響曲第4番

シュトラウス ティル

ワーグナー マイスター前奏曲

*フィラデルフィアにおける第3回定期

--------------------------------------

2067th 1926/3/9 Tue 4:30 PM .National Theatre

同 2066th

--------------------------------------

2068th 1926/3/10 Wed .Baltimore

同 2066th

*ボルティモアにおける最初のシーズン

--------------------------------------

2069th 1926/3/11 Thur 8:15 PM

.Strand Theatre Reading, PA

ベートーヴェン エグモント序曲

シュトラウス ティル

チャイコフスキー 悲愴

--------------------------------------

2070th 1926/3/12 Fri eve .Syria Mosque, Pittsburgh

ウェーバー オベロン序曲

シューマン 交響曲第1番

レスピーギ リュートの為の古い歌と舞曲、第2集

ブラームス ハンガリー舞曲(3曲)

--------------------------------------

2071st 1926/3/13 Sat aft .Syria Mosque, Pittsburgh

ハイドン 交響曲第13番

ドヴォルザーク 新世界

ワーグナー マイスター前奏曲

--------------------------------------

2072nd 1926/3/14 Sun 3:00 PM メトロポリタン・オペラハウス

ブラームス ヴァイオリン協奏曲

ヴァイオリン、ヨゼフ・シゲティ

チャイコフスキー 悲愴

--------------------------------------

2073rd 1926/3/18 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン レオノーレ序曲第3番

シェーンベルク 浄よめられた夜

ドヴォルザーク フス教徒 序曲

ラヴェル スペイン狂詩曲

ワーグナー さまよえるオランダ人 序曲

--------------------------------------

2074th 1926/3/19 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2073rd

--------------------------------------

2075th 1926/3/20 Sat 8:30 PM .CH

ウェーバー オベロン序曲

シェーンベルク 浄よめられた夜

シュトラウス ティル

ドヴォルザーク スラヴ舞曲(3曲)

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの10回目

--------------------------------------

2076th 1926/3/21 Sun 3:00 PM .CH

シューマン 交響曲第1番

サン・サーンス チェロ協奏曲第1番

チェロ、レオ・シュルツ

ベートーベン レオノーレ序曲第3番

--------------------------------------

2077th 1926/3/25 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ブルックナー 交響曲第4番

モーツァルト ピアノ協奏曲26番

ピアノ、ワンダ・ランドウスカ

ハイドン ハープシコード協奏曲

ハープシコード、ワンダ・ランドウスカ

ウェーバー オイリアンテ序曲

--------------------------------------

2078th 1926/3/26 Fri 2:00 PM .CH

同 2077th

--------------------------------------

2079th 1926/3/27 Sat 8:30 PM .CH

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第7番

ラヴェル スペイン狂詩曲

ワーグナー さまよえるオランダ人 序曲

*学生のための12回のコンサートシリーズの11回目

--------------------------------------

2080th 1926/3/28 Sun 3:15 PM .BAM

レスピーギ リュートの為の古い歌と舞曲、第2集

ラヴェル スペイン狂詩曲

チャイコフスキー 悲愴

--------------------------------------

2081st 1926/4/1 Thur 8:30 PM .CH

ヘンデル コンツェルト・グロッソ第5番

ウェーバー 舞踏への勧誘

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第3番エロイカ

--------------------------------------

2082nd 1926/4/2 Fri 2:30 PM .CH

同 2081st

--------------------------------------

フルトヴェングラーは脂がのりきっていたときに、ニューヨーク・フィルの定期を3シーズン振った。

1924-1925シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル83年目)

1925-1926シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル84年目)

1926-1927シーズン(ニューヨーク・フィル85年目)

最初のシーズン1924-1925シーズンはこんな感じ。

ウィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー指揮

ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニック

CH:カーネギー・ホール

BAM:ブルックリン・アカデミー・オブ・ミュージック

1925年1月3日 アメリカ初登場

--------------------------------------

1922nd 1925/1/3 Sat 8:30 PM CH

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

ハイドン チェロ協奏曲作品101

チェロ、パブロ・カザルス

ブラームス 交響曲第1番

--------------------------------------

1923rd 1925/1/4 Sun 3:15 PM BAM

同1922nd

--------------------------------------

1927th 1925/1/11 Sun 3:15 PM CH

ウェーバー 魔弾の射手、序曲

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第7番

ワーグナー トリスタンとイゾルデ

前奏曲と愛の死

ワーグナー マイスタージンガー、前奏曲

--------------------------------------

1928th 1925/1/15 Thur 8:30 PM CH

ヘンデル コンチェルト・グロッソ作品6-10

シューマン ピアノ協奏曲

ピアノ、オルガ・シュルツ

チャイコフスキー 交響曲第5番

--------------------------------------

1929th 1925/1/16 Fri 2:30 PM CH

ヘンデル コンチェルト・グロッソ作品6-10

シューマン ピアノ協奏曲

ピアノ、オルガ・シュルツ

チャイコフスキー 交響曲第5番

--------------------------------------

1931st 1925/1/18 Sun 3:15 PM CH

ヘンデル コンチェルト・グロッソ作品6-10

シュトラウス ティル

ブラームス 交響曲第1番

--------------------------------------

1932nd 1925/1/22 Thur 8:30 PM CH

ベルリオーズ ベンヴェヌート・チェリーニ、序曲

シューマン 交響曲第4番

ストラヴィンスキー 春の祭典

--------------------------------------

1933rd 1925/1/23 Fri 2:30 PM CH

同1932nd

--------------------------------------

1934th 1925/1/25 Sun 3:15 PM CH

メンデルスゾーン フィンガルの洞窟、序曲

シュトラウス ドン・ファン

チャイコフスキー 交響曲第5番

--------------------------------------

1936th 1925/1/30 Fri 8:30 PM CH

ハイドン 交響曲第94番 驚愕

シュトラウス 死と変容

ベートーヴェン 交響曲第5番

--------------------------------------

河童「この前お勧めしたライヴCD買ってみたのかね。」

静かな悪友S「聴いてみた。」

河童「それで感想は?」

S「あの指揮、とんでも棒だな。」

河童「だから前々から早く聴け、といっておいたのだ。」

S「予想以上だった。」

河童「あんなエキセントリックな演奏はないぜ。冒頭のコリオランはコレデモカといった超弩級の重さだし。春は、Spring has gone.っていう感じ。極度に引き延ばされ空中分解しそうな序奏を聴けば、もう終わってもいいのでは?とさえ思える。ブル4にいたっては、スケルツォのノリは誰もまねできないが、第4楽章の人間の限界を超えたキンチョールも鳥肌ものよ。」

S「どのような指揮者もまねできない解釈だし、まねしようとしても無理だな。プロセスがあって結果がついてきた、っていうことだからやはり天才技というところか。それにしてもオケをドライヴしすぎ。ウィーン・フィルよくついていけるよ。」

河童「おもしろすぎる演奏だ。」

S「これは定期?」

河童「ウィーン・フィルとのヨーロッパ・ツアーのなかでの演奏だ。10月5日のモントゥルーから始まって、ローザンヌ、チューリッヒ、バーゼル、パリ、ミュンスター、ハンブルク、ハノーファー、ドルトムント、ウッペルタル、デュッセルドルフ、ヴィースバーデン、ハイデルベルク、フランクフルト、シュトゥットガルト、カールスルーエ、そしてこの日が区切りのミュンヘン公演だ。」

S「ずいぶんと詳しいな。」

河童「追っかけをしたんだ。」

S「それにしても昔のプログラムは長かったんだね。」

河童「この日も休憩をいれて2時間半ぐらいかかってしまった。全プログラム胃袋に鉛を飲み込んでしまったようなヘヴィーな気分。」

S「こんな演奏毎日やっていたのかね。」

河童「そうゆうことだ。10月のミュンヘンの澄んだ空気の夜空に向かって怒髪天を衝く演奏にはもってこいのコンディションだったみたいだね。」

S「よくやるよ。ところで、このホールはドイツ博物館とあるが。」

河童「そうだ。ミュンヘンの川の中州にあるばかでかいドイツ博物館だ。」

S「博物館のロビーでやったのかね。」

河童「全部見るのに3,4日かかる博物館なので、いたるところにスペースがある。終わってからちょっと見学してみたけど、昔の防空壕の地下迷路のようなものがそのまま博物館の地下にあったりする、とんでも館だ。」

S「こんどフュッセンの白鳥のお城に登って、その足で寄ってみるか。」

河童「それがいい。河童はライン川をもぐってコブレンツの例の〆鯖の居酒屋で一服してから北に向かう。」

S「それはそうと、お河童さんはF協会会員になってどのくらいになるの?」

河童「そうだね。河童歴132年からだから、もうかれこれ30年以上だね。」

S「こんな限界演奏をいつも早目に入手していたのかな。」

河童「この演奏は河童歴109年のもので、現場で盗み録音をしてあらぬ方向にばら撒いたら、河童歴128年頃にLP化された(市販2枚)。」

S「昔から音も盗んでいたと言うことか。」

河童「人聞きが悪いな。エキセントリック・コンサートの世界遺産化だ。」

S「ものはいいようだな。」

河童「昔のF協会は市販されていない音源の連発で有意義だった。会員も熱かった。一番印象に残っている協会レコードは、例のドイツ亡命前夜のフランクとブラ2の何を何処にそんなに急ぐクレイジーな演奏。あれはすごかった。ご本人は結局、スキーでスイスにでたという噂もある。」

S「それでF協会は?」

河童「歴史はすすみ、録音の著作権切れになったあたりからインディーズ系の小規模な会社などが同じ音源の繰り返し発売の連発で新鮮味がなくなった。F協会も同じ音源の繰り返し発売ばかり。主眼は新録音ではなく、同じ音源でいい音のCDをだすこと。という奇妙な現象が発生した。それに最近のF協会は、利益をあげているのではないかというきな臭い噂もあるようだ。いずれにしてもご本人は1954年没だから、これ以降の新譜はないわけで、オタク連中にとっては範囲が確定している分、コレクトしやすいのだろう。僕はもう卒業だ。全部聴いた。スカラ座とのステレオのパルジファルがあるという噂もあるが、発見されて発売されればすぐにとびつくだろうが、これまでの焼き直しCDはもうたくさんだ。基本的にあたらしものずきだし。」

S「なるほどね。オタク寸前で踏みとどまったんだね。」

河童「でも、いまだに会員。某ネットでは最近までかなり名が売れていた。理由はまたいつかチャンスがあれば教えるよ。」

S「楽しみにしてるよ。」

1951年10月29日 ミュンヘン、ドイツ博物館

ベートーヴェン コリオラン序曲

シューマン 交響曲第1番 春

ブルックナー 交響曲4番

ウィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラー指揮ウィーン・フィル

●

おわり