There Are Three Versions of Bruckner’s Fourth. Why Choose?

Jakub Hrusa and the Bamberg Symphony have released a new recording of them all.

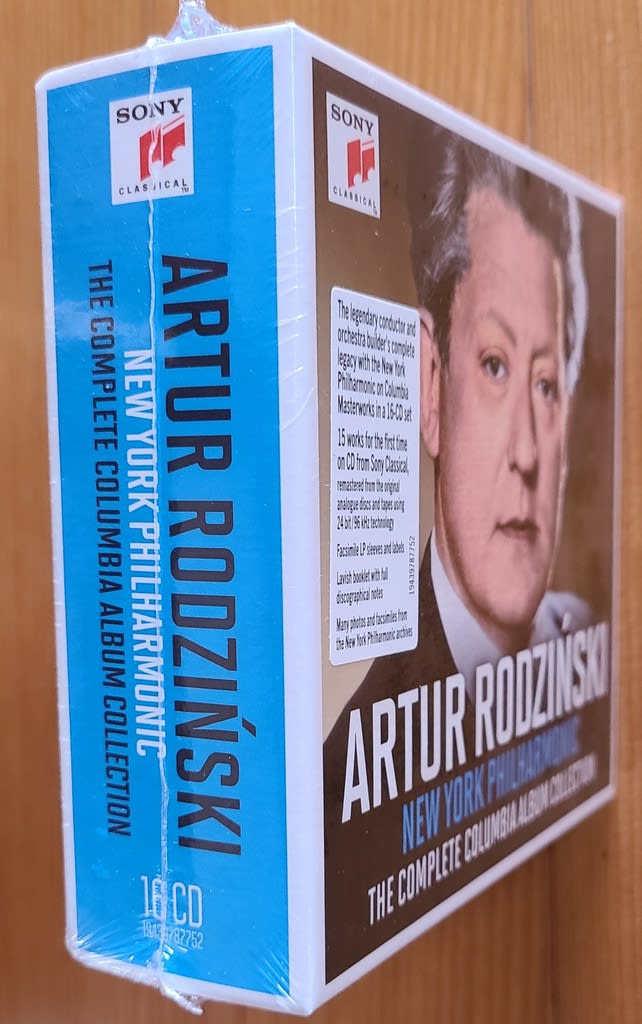

The conductor Jakub Hrusa and the Bamberg Symphony, which he has led since 2016, have released a recording of all three versions of Bruckner’s Fourth.

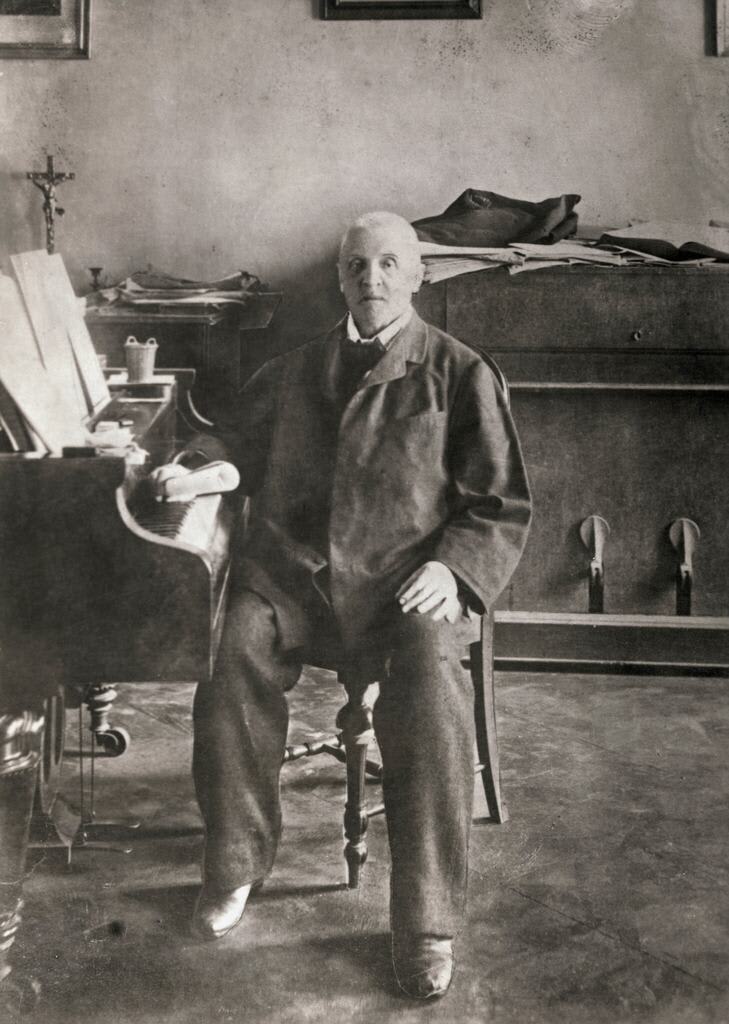

The Austrian composer Anton Bruckner died in 1897, but his Fourth Symphony remains something of a work in progress.

Bruckner kept revisiting and revising many of his nine long symphonies, which in turn have been re-edited and tweaked by a series of followers, publishers and scholars. The result is that seven of the nine now exist in multiple scores.

The burden is on musicologists and conductors to decide which iteration is the most authentic, or just the best. And that problem is most acute with the Fourth Symphony, which Bruckner worked on longer than the others — from his first version, which dates to 1874 and was never performed in his lifetime, to a final third version, which premiered in Vienna in 1888. Following a critical reconsideration of Bruckner’s symphonies in the 1930s and ’40s, the second version, dating from 1880, became the standard.

This month, the Bamberg Symphony in Germany, led by its chief conductor, Jakub Hrusa, embraces the problem of the Fourth — or simply overwhelms it. The orchestra is releasing a four-disc set that includes recordings of all three versions, in new editions edited by Benjamin Korstvedt, a professor at Clark University in Massachusetts, as part of the ongoing complete Bruckner being published under the auspices of the Austrian National Library. (For good measure, the recording also includes a selection of unpublished alternate passages and an alternate finale.)

A native of the Czech city of Brno, Hrusa, 40, has led the orchestra in Bamberg, a small Bavarian city north of Nuremberg, since 2016. He has also appeared as a guest on major podiums, including several visits to the Cleveland Orchestra, and recently conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in the premiere of a new work by Olga Neuwirth — as well as in the second version of Bruckner’s Fourth.

While in Berlin, he gave a video interview from his hotel. Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Why did you decide to record, well, everything about the Fourth Symphony?

It took me a relatively long time to explore Bruckner with satisfaction. I had conducted his music before, but I was never really pleased. Then I got to Bamberg. Bruckner’s music is very much at home in German-speaking countries, and I suddenly had an orchestra that just breathes this kind of music. I felt like I wanted to do a lot of it, and we began with the Fourth Symphony.

I was rather innocent and didn’t have any experience with all the versions. Bamberg usually plays the second version, so I said, “Let’s do the third one,” which at the beginning of the 20th century was basically the only one that was performed. And then I wondered: Is the third version really the right one? Or is the second one right? And what about the very first version? And suddenly the idea came to record them all and bring out something new. There is so much Bruckner on the market, and if you record him again, it should have some bonus quality.

What are the key differences between the three versions? And do you now prefer one?

I was intrigued by the first version, because it is by far the most controversial, and the boldest. It is longer and has a completely different scherzo [the third movement], and there are certain passages that are on the edge of being unplayable. I don’t agree with people who say it is not good; it’s just not practical. But if you do it well, it sounds very contemporary. It’s now probably my favorite. If there is enough time to prepare, and the possibility to mount such a huge piece in concert, I would be eager to conduct it again.

Bruckner’s music was promoted by 19th-century German nationalists and 20th-century Nazis. Should that concern audiences today?

I am interested in these things, and I am very happy to read about them, but I don’t think we should care when we’re listening to the music. Great music can stand all kinds of analysis, but it also needs no analysis at all to be appreciated, and I don’t want to spoil the pleasure for people who go to a concert with no clue about those contexts. They have a right to be exposed to Bruckner’s music as it is. What has been done with the music shouldn’t be projected onto the interpretation.

And Bruckner (unlike, say, Wagner) didn’t provoke the controversies himself. He was a devout Catholic, and he had certain views of life that might not seem very modern, but — apart from dedicating his last symphony to his “beloved God” — they were not made explicit.

What are the challenges in maintaining a world-class orchestra in a small provincial city?

It’s much easier to promote an orchestra connected to a well-known city. Bamberg has about 70,000 inhabitants, and we have 6,000 subscribers — so roughly 10 percent of the adult population comes to our concerts. We feel like the flagship of the town.

But the orchestra has always thought that its mission must go beyond Bamberg. In continental Europe, the Bamberg Symphony has a name, but almost no one in the United States, for instance, knows where Bamberg is. As soon as people hear a recording or come to a concert, they discover the quality for themselves. But before that happens it takes twice as much as effort to open people’s minds.

Sometimes you use a baton and sometimes you don’t. How do you decide?

The baton is an elongation of the arm. It is only really needed in an opera house, where you have to be extremely clear so that everyone onstage can see you. And if you do a piece by Olga Neuwirth, where the meter changes in every bar and the musicians are dependent on every click of your hand, it is useful to have it. But if the orchestra doesn’t need clear indications, and the music flows in a way that doesn’t need a beat, then I can do without a baton. But I am not dogmatic about it; it’s just intuition.

You are a fierce advocate for the prolific Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu. Czechs place him alongside Smetana, Dvorak and Janacek, but he is much less known abroad.

If a composer writes so many pieces, as Martinu did, you can’t play all of them. The public needs focus, and you have to kind of shrink the heritage. In the case of Martinu, it is not so easy to do. I find that my task is to limit myself to his late period, when he was most original. And then I try to win over an orchestra, which is the first thing for a conductor. If the audience sees that the orchestra is playing with great pleasure and energy and effort, they take it for granted that it’s worth it.

You have what could be called an effervescent conducting style — very physically exuberant. How did you develop that?

It has taken me years. Even though I am overwhelmed with joy at what I do, I am also a very self-critical person. I started in a more controlling way, and I had to learn that the best results happen in a concert when you open yourself up to whatever comes.

The usual mistake of the beginner is to conduct like crazy when it’s not needed. I had to find a way to navigate the orchestra so that they get something that is helpful — not only technically, but also in terms of atmosphere and energy. In a Bruckner symphony, for example, there are 70 minutes of music, and the energy level of the musicians inevitably goes down. It’s my job to guide things so that the audience never feels that.

おわり