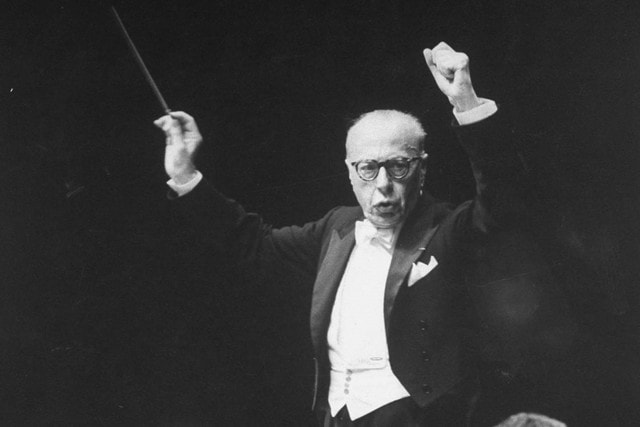

‘George Szell: The Complete Columbia Album Collection’ Review: A Maestro’s Time in Cleveland Still Shines

wsj 2018.8.22

Music Review

‘George Szell: The Complete Columbia Album Collection’ Review: A Maestro’s Time in Cleveland Still Shines

This 106-CD set assembles almost all of the conductor’s recordings with the Cleveland Orchestra, along with a few Szell made with the New York Philharmonic, the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, and as a remarkably vibrant chamber-music pianist.

When George Szell died, in 1970, he was revered for having built the Cleveland Orchestra into one of the world’s great ensembles in a 24-year tenure that began in 1946, and as an interpreter whose streamlined but high-power readings were rooted in his belief that a composer’s intentions were sacrosanct. But though he played down the Romantic notion that interpretation should also reflect the performer’s personality, Szell’s readings were always identifiable by their structural logic, textural clarity, unerring balances and sheer energy. Under Szell’s baton, an orchestra was a highly polished, precision machine, and in music by Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Dvo?ak and Wagner, he was untouchable.

Yet, at the time of his death, the music world as Szell knew it was hurtling toward obsolescence. One of the last great podium martinets, Szell wielded absolute authority and executed it with severity?an approach that vanished once unions began asserting themselves in matters of how musicians should be treated. Vanished, too, is the kind of devotion Szell showed to the Cleveland Orchestra. These days, a tenure lasting nearly a quarter century is rare; beyond a decade, critics wonder (often abetted by off-the-record carping from the players) whether the relationship is growing stale.

Szell’s, with Cleveland, never did; the chemistry between them consistently yielded both heat and light. Their recordings for the Epic and CBS Masterworks labels, starting in 1947, were exemplary in their day, and they remain so now, a point Sony Classical makes vividly in its 106-CD “George Szell: The Complete Columbia Album Collection,” out now. Except for some live recordings issued by the orchestra itself, all of Szell’s Cleveland recordings are here, along with a few Szell made with the New York Philharmonic, the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, and as a remarkably vibrant chamber-music pianist. The discs are beautifully remastered, and packaged in sleeves that replicate their original artwork and liner notes, with period-correct labels and a hardcover book that provides all the recording details.

Mammoth boxes like this, which have become plentiful lately, are the last gasps of the physical record industry, intent on presenting its wares as they were in their heyday, one last time before streaming blows away the tactile side of music collecting entirely. They are comprehensive, relatively inexpensive (the Szell set can be had for less than $2 a disc) and provide the eerie sense that you are holding the full shape and substance of a great musician’s career in your hands.

The Szell box is a fascinating glimpse at how the supposedly ossified classical canon has evolved (albeit slowly) over the decades. There is, for example, very little Mahler or Bruckner, indispensable staples of a conducting career now. But what there is?most notably, a rich-hued 1966 Mahler Fourth Symphony, and a broad-boned 1970 Bruckner Eighth?stands up well to modern competition. It is also hard to imagine a conductor today recording 106 discs with only a handful devoted to contemporary music and, of that, only a single Stravinsky work, the “Firebird” Suite.

Yet when Szell considered a new work worth recording?for example, a spiky, high-contrast account of Samuel Barber’s Piano Concerto, with John Browning; or taut, colorful performances of Walton’s Partita for Orchestra and Symphony No. 2; or a curious reading of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra that begins sedately but eventually explodes from the speaker?he is an eloquent advocate, as focused on detail, balance and the subtleties of color as he is in the great Romantic works.

There are occasional disappointments that have more to do with changing interpretive fashion than with any deficiencies of Szell’s. His Mozart, Haydn and Bach, for example, sound a bit ponderous by today’s standards. And despite his reputation as a literalist, he often jettisoned exposition repeats, arguing in interviews (several are included in the set) that repeats were necessary only when works were new and audiences were unfamiliar with them.

Szell’s specialty was the Romantic repertory. His Beethoven and Brahms Symphonies remain among the most tightly reasoned and precisely executed on the market, and his collaborations on those composers’ piano concertos, with Leon Fleisher, are still the gold standard. It’s not easy to find a recording that captures the same level of urgency and anxiety Szell brought to Strauss’s “Death and Transfiguration,” and his Wagner Overtures are truly regal. Even pieces that, today, are typically curtain-raisers or encores?Rossini Overtures, the Dvo?ak “Slavonic Dances”?have an uncommon intensity that makes them sound like major statements.

Lately, the sweep of reductive history has elevated Arturo Toscanini, Leonard Bernstein and Herbert von Karajan to almost mythic status, leaving the other great conductors of the 20th century as footnotes that only specialist collectors care about. That’s not how it seemed at the time, of course. And the new Sony box is a reminder, disc for disc, that Szell deserves a place in that pantheon.

?Mr. Kozinn writes about music for the Journal.