WSJ記事全文と機械翻訳

Artur Rodzinski—New York Philharmonic: The Complete Columbia Album Collection Review: Mercurial Maestro

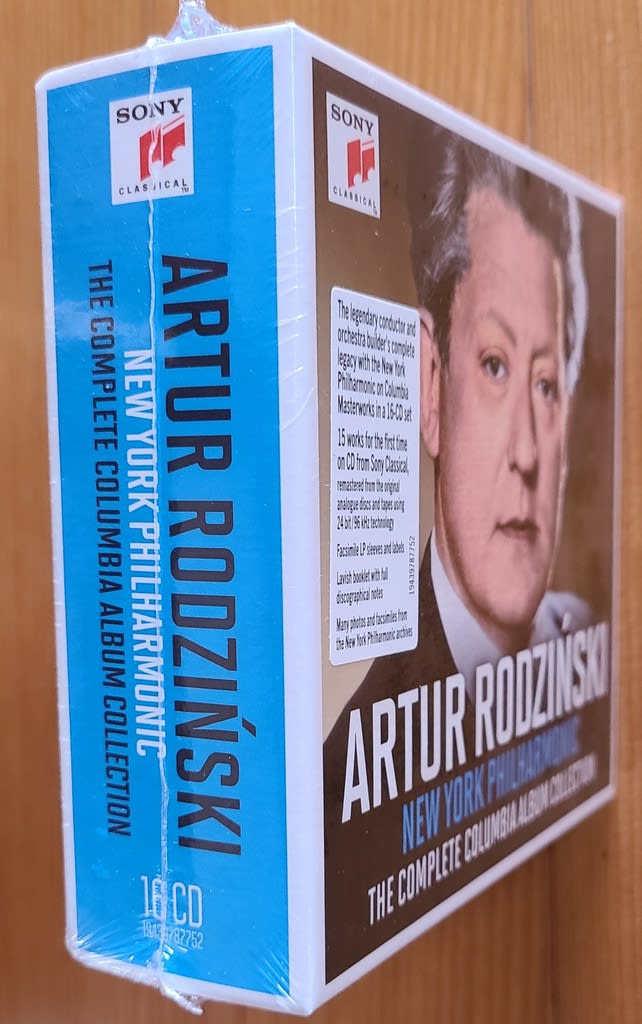

A 16-CD boxed set celebrates a 20th-century Polish conductor who reinvigorated the music of composers from Brahms to Gershwin and was, for a time, the premier orchestra builder in the U.S.

By David Mermelstein April 26, 2021

If the name Artur Rodzinski means little to music lovers today, that’s because time and more media-savvy maestros have eclipsed his fame. But from the 1930s till his death in 1958, this Polish conductor had the respect not just of audiences, but also of musicians, including his peers on the podium. Now one of his great contributions to American musical life—his directorship of the New York Philharmonic in the mid-1940s—is being celebrated thanks to a new compilation of recordings. Titled “Artur Rodzinski—New York Philharmonic: The Complete Columbia Album Collection,” the box of 16 CDs from Sony Classical also contains material from several years later with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, but not, alas, Rodzinski’s earlier Columbia recordings with the Cleveland Orchestra nor his later records with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on RCA.

Rodzinski (pronounced roh-JIN-skee), the son of an army medical officer, was born in 1892 in the Dalmatian city of Split, then part of the Habsburg Empire. His studies eventually took him to Vienna, where he trained under such musical luminaries as the composer Franz Schreker, the conductor Franz Schalk and the pianist Emil von Sauer. Leopold Stokowski spotted his talent and appointed him his assistant at the Philadelphia Orchestra, where the younger conductor’s fame quickly grew. Posts in Los Angeles and Cleveland soon cemented his standing as this country’s pre-eminent orchestra builder, with him laying the groundwork on which others erected, or at least burnished, their reputations.

A peak in this regard came in 1937, when Arturo Toscanini chose him to select and train the members of the radio orchestra that NBC was creating in New York for the venerable Italian maestro. So when the New York Philharmonic (then styled as the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York) needed a new chief conductor, Rodzinski seemed an obvious choice. A longstanding commitment to opera in concert and new music, along with his mastery of wide swaths of the canon, left little, if anything, beyond his reach.

Yet great talent sometimes breeds great conflict—or so it was with Rodzinski’s perfectionist tendencies and artistic ambitions. He was the first to carry the title of music director at the Philharmonic and summarily dismissed 14 players. (He was also, almost certainly, the last to carry a loaded pistol to performances!) But he was unskilled at playing musical politics, and his abbreviated tenure, from 1943 to 1947, was the subject of a harsh Time magazine cover story.

These recordings, however, tell a different tale—one of confident leadership and great brio, but also of musical tenderness and warmth. Rodzinski was sensitive to structure and balance yet completely dedicated to delivering exciting, often thrilling, performances. In this box, works by over 20 composers receive readings that attest to his protean talents. Scores that have never left the concert bill—like Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition,” Gershwin’s “An American in Paris” and Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait”—abut pieces that were once, but are no longer, standard repertory, including Jacques Ibert’s “Escales,” Georges Enesco’s Romanian Rhapsody No. 1 and Bizet’s Symphony in C.

Though no symphonies by Beethoven figure here, incandescent accounts of Brahms’s First and Second Symphonies provide ample gravity. And Sibelius’s searching Symphony No. 4 lacks for nothing in Rodzinski’s hands. But Russian symphonies lay a special claim, including a model performance of Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique,” with lively woodwinds, refulgent brasses and brooding strings. Rodzinski’s landmark account of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony retains its impact, and his version of Rachmaninoff’s sprawling Symphony No. 2 (cut as was the custom then) still seduces. Other music by these composers further enlivens this collection, most notably a delectable performance of Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker” Suite, with an equal measure of vim and exoticism.

His abrupt exit from New York—after resigning, he was essentially fired—did not leave Rodzinski without a podium. He had been negotiating surreptitiously with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and he slid from one job into the other without pause. But the administrative problems that dogged him on the East Coast were no less present in the Midwest. He lasted a mere 10 months in Chicago and never held a prominent post again.

Rodzinski’s last years were spent largely in Europe, where he successfully freelanced and began recording for Westminster. He died in Boston at age 66, shortly after conducting Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” in Chicago, but not before making a series of extraordinary stereo recordings for EMI in London, in which his talents as an orchestral colorist emerge to fullest effect. Those recordings aren’t readily available on CD, but perhaps this set will spur their reissue, along with the remaining treasures in the Columbia and RCA archives.

—Mr. Mermelstein writes for the Journal on classical music and film.

機械翻訳

「アルトゥール・ロジンスキー- ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー:コロンビア・アルバム・コレクション全集」レビュー:マーキュリアル・マエストロ

16枚のCDボックスセットは、ブラームスからガーシュウィンまで作曲家の音楽を再活性化し、しばらくの間、米国で最高のオーケストラビルダーだった20世紀のポーランドの指揮者を祝います。

アルトゥール・ロジンスキーという名前が今日の音楽愛好家にとってほとんど意味がないなら、それは時間とより多くのメディアに精通したマエストロが彼の名声を食い止めたからです。しかし、1930年代から1958年に亡くなるまで、このポーランドの指揮者は観客だけでなく、表彰台の仲間を含むミュージシャンにも敬意を払っていました。1940年代半ばにニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団の監督を務めたアメリカの音楽生活に大きな貢献をした彼の一人は、録音の新しいコンピレーションのおかげで祝われています。「アルトゥール・ロジンスキー-ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー:完全なコロンビア・アルバム・コレクション」と題されたソニー・クラシックのCD16枚には、数年後のコロンビア交響楽団の資料が含まれていますが、悲しいかな、ロジンスキーの以前のコロンビア・レコーディングはクリーブランド・オーケストラとの録音もRCAのシカゴ交響楽団との彼の後のレコードです。

陸軍医療官の息子であるロジンスキー(roh-JIN-skeeと発音)は、1892年に当時ハプスブルク帝国の一部であったダルマチアの都市スプリットで生まれました。彼の研究は最終的にウィーンに連れて行き、作曲家フランツ・シュレーカー、指揮者フランツ・シャルク、ピアニストのエミール・フォン・ザウアーなどの音楽界の著名人の下で訓練を受けました。レオポルド・ストコフスキは彼の才能を見つけ、若い指揮者の名声がすぐに成長したフィラデルフィア管弦楽団で彼のアシスタントを任命しました。ロサンゼルスとクリーブランドのポストはすぐに、彼は他の人が建てた、または少なくとも焼き払った、彼らの評判を建てた、または焼き払った基礎を築いて、この国の著名なオーケストラビルダーとしての彼の地位を固めました。

この点でピークが来たのは1937年、アルトゥーロ・トスカニがNBCがニューヨークで作っていたラジオオーケストラのメンバーを選んで訓練することを選んだ時でした。ニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団(当時はニューヨークのフィルハーモニー交響楽団としてスタイリング)が新しい首席指揮者を必要としたとき、ロジンスキーは明らかな選択のように思えました。コンサートや新しい音楽のオペラへの長年のコミットメントは、カノンの広い範囲の彼の習得と一緒に、彼の手の届かないところにほとんど残っていません。

しかし、偉大な才能は時には大きな対立を生み出すのか、それともロジンスキーの完璧主義の傾向と芸術的野心と共に生まれた。彼はフィルハーモニー管弦楽団で音楽監督の称号を最初に背負い、14人の選手を解任した。(彼はまた、ほぼ確実に、ロードされたピストルを公演に運ぶ最後の人でした!しかし、彼は音楽政治を演じるのに熟練し、1943年から1947年までの彼の略語の任期は、厳しいタイム誌のカバーストーリーの主題でした。

しかし、これらの録音は、自信に満ちたリーダーシップと偉大なブリオの1つだけでなく、音楽の優しさと暖かさの別の物語を伝えます。ロジンスキーは構造とバランスに敏感でしたが、エキサイティングで、しばしばスリリングなパフォーマンスを提供することに完全に専念していました。このボックスでは、20人以上の作曲家の作品は、彼のプロテアンの才能を証明する読書を受け取ります。ムソルグスキーの「展覧会の絵」、ガーシュウィンの「パリのアメリカ人」、コープランドの「リンカーンの肖像画」など、コンサート法案を離れたことがない楽譜は、ジャック・イベールの「エスカル」、ジョルジュ・エネスコのルーマニア狂詩曲第1番、ビゼート交響楽団など、かつては存在しなかったが、もはや標準的なレパートリーではない作品です。

ベートーヴェンの人物による交響曲はありませんが、ブラームスの第1交響曲と第2交響曲の白熱の記述は十分な重力を提供します。そして、シベリウスの探す交響曲第4番は、ロジンスキーの手には何の欠けにも欠けている。しかし、ロシアの交響曲は、活気に満ちた木管楽器、勤勉な真鍮、ブローディング弦でチャイコフスキーの「パテティーク」のモデルパフォーマンスを含む特別な主張を置いています。ロジンスキーのプロコフィエフの交響曲第5番の画期的な記述は、その影響を保持し、ラフマニノフの広大な交響曲第2番(当時の習慣のようにカット)の彼のバージョンはまだ誘惑します。これらの作曲家による他の音楽は、このコレクション、特にチャイコフスキーの「くるみ割り人形」スイートのおいしいパフォーマンス、バイムとエキゾチックの同等の尺度でさらに盛り上がっています。

彼が突然ニューヨークを去ったのは、彼が辞任した後、彼は本質的に解雇されたが、表彰台なしでロジンスキーを去らなかった。彼はシカゴ交響楽団と密かに交渉していたし、彼は一時停止することなく、他の仕事から滑り落ちた。しかし、東海岸で彼を悩ませた行政上の問題は、中西部に劣らず存在していました。彼はシカゴでわずか10ヶ月続き、二度と著名なポストを保持しませんでした。

ロジンスキーの最後の年は主にヨーロッパで過ごし、そこでフリーランスに成功し、ウェストミンスターのレコーディングを始めました。彼はシカゴでワーグナーの「トリスタン・ウント・イゾルデ」を指揮した直後にボストンで66歳で亡くなりましたが、ロンドンでEMIの特別なステレオ録音を行う前に、オーケストラのカラー主義者としての才能が最大限に発揮されます。これらの録音はCDですぐに入手できませんが、おそらくこのセットはコロンビアとRCAアーカイブの残りの宝物と一緒に再発行に拍車をかけるでしょう。

おわり