CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK

A Conductor’s Impossible Legacy

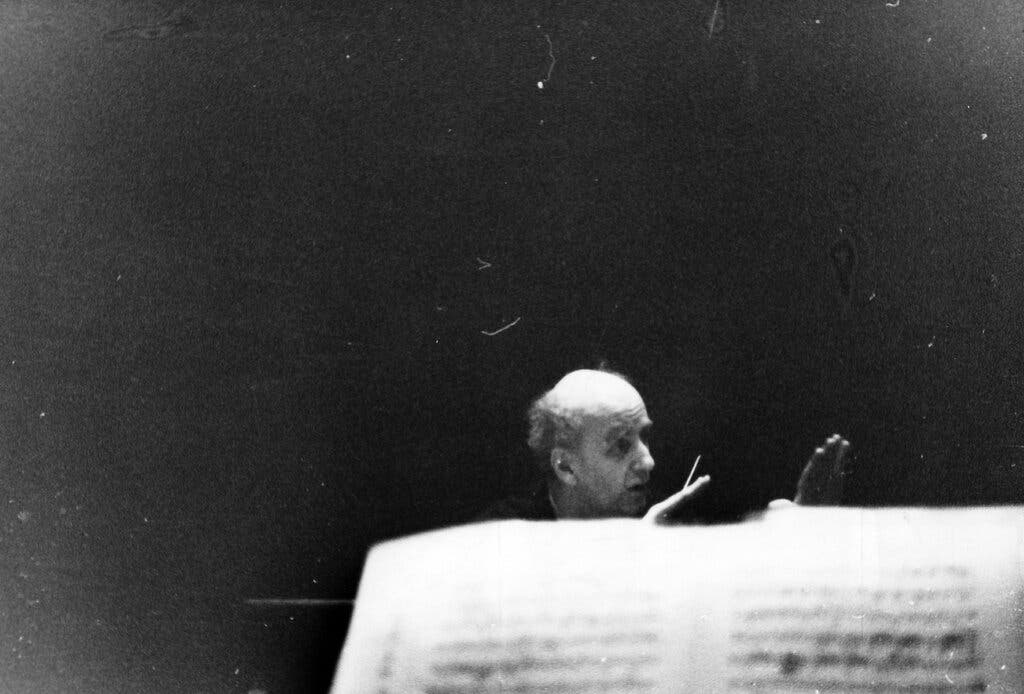

The sublime artistry of Wilhelm Furtwängler collided with his role as de facto chief conductor of the Nazi regime.

By David Allen Oct. 14, 2021

We live in a time of intense scrutiny of the moral failings of artists — even, or perhaps especially, those whose creations we admire. And in few classical musicians is the gap between sublime work and shameful actions greater than the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler.

Consumed by an exalted belief in the power of music, and preternaturally able to convince listeners of that power, Furtwängler conducted Beethoven and Brahms, Bruckner and Wagner, with proprietary authority, as if he alone could reveal their deepest psychological, even spiritual, secrets.

Sometimes it sounds like he could. With his expressive, flexible approach to tempo and dynamics, Furtwängler breathed the structure of a whole piece into each of its measures, while making each measure sound as if improvised. Ask me to show you what the point of a conductor is — what a conductor can achieve — and I would point you to a Furtwängler recording.

The problem is that Adolf Hitler would point to him, too. For Hitler, Furtwängler was the supreme exponent of holy German art; it was to the Nazis’ satisfaction that he served — in effect if not in title — as the chief conductor of the Third Reich.

The complications are many. Furtwängler never joined the Nazi party, and after his initial protests over the expulsions of Jewish musicians and the erosion of his artistic control were resolved in the Nazis’ favor in 1935, he found ways to distance himself from the regime, not least over its racial policies. His performances with the Berlin Philharmonic and at the Bayreuth Festival at once served the Reich and gave succor to those who sought to survive it, even oppose it.

“At Furtwängler’s concerts, we all became one family of resistance fighters,” one opponent of the Nazis said.

Joseph Goebbels nevertheless had little doubt that Furtwängler was, as he put it, “worth the trouble.” Furtwängler avoided conducting in occupied countries, but, for example, led the Berlin Philharmonic in Oslo one week before the German invasion of Norway in April 1940. He declined to conduct during the Nuremberg rallies, but was satisfied to appear just before them — including, in 1938, with the forces of the Vienna State Opera, immediately after the Anschluss.

Whatever considerable aid Furtwängler may have offered to some in need, he was stained. Given the cover he had offered the “regime of the devil,” the émigré conductor Bruno Walter asked him after the Second World War, “of what significance is your assistance in the isolated cases of a few Jews?”

Acrimonious enough in Furtwängler’s lifetime — when protests forced him to withdraw from posts he had been offered at the New York Philharmonic, in 1936, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, in 1949 — the debate raged on after his death, in 1954.

Time brought distance, reconciliation and research. Musicians took up Furtwängler’s cause, with Daniel Barenboim in the lead. Books rehabilitated the erstwhile collaborator. One, by Fred Prieberg, declared Furtwängler a “double agent”; another, by Sam Shirakawa, described him, absurdly, as doing more to thwart the Nazis than anyone else, as if he were Dietrich Bonhoeffer with a baton.

Recording after recording emerged — mostly archived radio broadcasts, some of extraordinary quality. Distressingly, Furtwängler turned out to have been at his most intensely visionary during the war, performing for an Aryanized audience at the helm of a purged Berlin Philharmonic.

Those wartime tapes only added to the Furtwängler riddle, though. Was the frenzied Beethoven Ninth he gave in Berlin in March 1942 an act of resistance, scorched in sound? Or was it more proof that “the fate of the Germans” was to “unify things that appear impossible to unify,” as he put it in 1937?

“German music proves,” he had continued then, “that the Germans have achieved such victories before.” Hitler evidently thought so. Furtwängler was filmed shaking Goebbels’s hand after having been maneuvered into reprising the symphony for the Führer’s birthday, one month later.

Despite our current climate, the temptation remains to move past these difficulties, rather than confront them yet again. That seems to be the thinking behind a new set from Warner Classics, 55 CDs that announce themselves as the “The Complete Wilhelm Furtwängler on Record.”

Compiled with the aid of Stéphane Topakian, a former vice president of the Société Wilhelm Furtwängler, a French organization founded in 1969, the box represents a rare sharing of the back catalogs of Warner and Universal. It takes listeners from Furtwängler’s first, timid recordings of Weber and Beethoven, in 1926, through classic accounts like his Tchaikovsky Sixth from 1938 and his Beethoven Ninth from 1951, to the towering “Die Walküre” he taped a month before his death.

Listen to the box, and if you’re left wondering whether microphones ever truly captured Furtwängler’s carefully calibrated dynamics and his as-if-from-the-depths sound, you still find ample, glorious evidence of his famous long line, his ability to make scores cohere. You also find that he was not at all the invariably slow, monumental conductor he is often remembered as. There is touching warmth in his “Siegfried Idyll,” delicacy and charm in his Haydn, dignity in his vivacious Mozart.

Throughout, there is a sense of hearing a world lost, of a conducting style dating back to Richard Wagner that, with its deliberate imprecisions and its privileging of the perceived spirit behind the music over its textual details, aims at something quite different than maestros do today.

What Warner’s box is not, however, is the complete Furtwängler on record. His discography has always been the subject of debate, as has his conflicted attitude to the medium, but Warner has limited itself to his studio efforts and the live recordings he made with an express view to commercial sale.

Strangely, those criteria have led to the inclusion of recordings that Furtwängler decided not to release, like the “Walküre” and “Götterdämmerung” from a “Ring” he led in London in 1937. And myriad live recordings are left out, even those that have previously appeared on Warner and Universal labels, including his rampage through Strauss’s “Metamorphosen” in 1947; his astounding “Ring” for Italian radio in 1953; his destructive, distraught accounts of Brahms’s Third and Fourth; and almost all of his mystical Bruckner.

Perhaps that decision isn’t so baffling when you consider that omitting all but a few live tapes means dedicating fewer than two discs to the war, the defining period of Furtwängler’s life. The timeline provided in the notes coyly states, in the present tense, that he “limits his activities” during the war years, though finds himself “obliged to participate in certain official events.” Topakian, the box’s curator, writes that a postwar Beethoven Seventh in Vienna represents Furtwängler “at his purest,” while the intensity of his Berlin account from 1942 was “nothing to do with the work.” Some amnesia is at play here.

But however often Furtwängler declared himself an apolitical artist, his conservative, nationalistic worldview was never separable from his conducting, as the musicologist Roger Allen has shown — not even after 1945, when most of the recordings in the Warner box were made.

Born to an archaeology professor and a painter in 1886, Furtwängler grew up thinking of himself as a Beethoven in waiting. But the reviews of his early compositions were savage; he did not return to composing in earnest, the historian Chris Walton has found, until the mid-1930s, when Nazi cultural policy savaged modernism and made room for his interminable, quasi-Brucknerian wanderings.

Furtwängler met no such resistance as a conductor. After a series of minor posts, notably in Mannheim, he became chief conductor of both the Berlin Philharmonic and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1922, later dropping the Leipzig position for one with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Through this period, Furtwängler set out an aesthetic that has uncomfortable resonances today. His promotion of the indomitable supremacy of German art was a major part of this — even if he conducted Schoenberg despite his hatred of modernism. But his methods of analyzing scores and even his theory of conducting were expressed in chauvinistic language. He wrote that music should not be banned — that is, “unless it is a clear case either of rubbish or kitsch or of anti-state cultural Bolshevism.”

The rise of conducting styles that challenged his — above all the textual literalism of his rival, Arturo Toscanini — confirmed for him that the Weimar Republic was a Germany in crisis. Despite his differences with the Nazis, it seems likely that he, like most conservatives, welcomed their takeover as a return to an authoritarian, Wilhelmine past — a process through which the art he perceived as lesser would be excised.

Even after Furtwängler fled Germany early in 1945, following a warning from Albert Speer of threats to his safety, and after he was cleared in a denazification trial in 1946, this worldview lingered. As late as 1947, he was still hailing the “organic superiority” of the German symphonists; two years later, he decried the “biological insufficiency” of atonality.

Nor did Furtwängler step back from grandiose claims about the power of music, and his role as its savior. Astonishingly, he thought it wise to write to colleagues in 1947 that “a single performance of a truly great German musical composition was by its nature a more powerful, more essential negation of the spirit of Buchenwald and Auschwitz than all words could be.”

Warner’s box makes clear that he made marvels in the postwar years, including the pained formalism of his Gluck overtures; the utter revelation of his Schumann Fourth; a heaven-storming “Fidelio”; and a “Tristan und Isolde” that remains unsurpassed since its recording in 1953.

But just as Furtwängler was naïve to claim toward the end of the war that he was proof that a “completely unbroken nation” was still alive and well, that he had carried Beethoven, Brahms and Wagner through the conflict unscathed, so it would be naïve to think of those later interpretations as somehow separate from what had come before.

And dangers from Furtwängler’s legacy still linger in classical music today: the myth he perpetuated of the singular genius; the idea that Beethoven or Brahms are frictionlessly “universal” in their art and impact; the false ideal that music floats, perpetually unsullied, above politics. As for the man himself, it speaks to the lasting power of Furtwängler’s artistry that we still demand so much of him morally — more, for example, than of Herbert von Karajan, who joined the Nazi party, or Karl Böhm, who hailed Hitler from the podium.

Chris Walton, the historian, has suggested that, given all of his intellectual and aesthetic affinities with the Nazis, perhaps the question to ask is not, as it used to be, why he stayed in Germany. Rather, it might be why this man who was “all but ‘predestined’ to become a model Nazi,” as Walton writes, did not — not quite. In that, there remains a glimmer of light, for him and for us.

おわり

機械翻訳

批評家ノート

指揮者の不可能な遺産

ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの崇高な芸術性は、ナチス政権の事実上の首席指揮者としての彼の役割と衝突しました。

デビッド・アレン2021年10月14日

私たちは、芸術家の道徳的な失敗、あるいは特に私たちが賞賛する作品を持つ人々を厳しく精査する時代に生きています。そして、少数のクラシックミュージシャンでは、指揮者ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーよりも崇高な仕事と恥ずべき行動の間のギャップがあります。

音楽の力に対する高貴な信念によって消費され、自然にその力のリスナーを説得することができ、 フルトヴェングラー は、彼だけが彼らの最も深い心理的、精神的な秘密を明らかにすることができるかのように、独自の権威を持つベートーヴェンとブラームス、ブルックナーとワーグナーを指揮しました。

時にはそれは彼ができるように聞こえます。テンポとダイナミクスに対する彼の表現力豊かで柔軟なアプローチで、フルトヴェングラーは、各尺度を即興のように音を出しながら、その各手段に全体の部分の構造を呼吸しました。指揮者のポイント(指揮者が達成できるもの)を教えてもらい、フルトヴェングラーの録音を教えてください。

問題は、アドルフ・ヒトラーも彼を指し示すだろうということです。ヒトラーにとって、フルトヴェングラーは聖ドイツ美術の最高の指数でした。第三帝国の首席指揮者として、彼が事実上、称号に入っていなくても、ナチスの満足に仕えたのです。

合併症は多いです。 フルトヴェングラー はナチス党に加わったことがなく、ユダヤ人ミュージシャンの追放と彼の芸術的支配の侵食に対する彼の最初の抗議が1935年にナチスの有利に解決された後、彼は少なくともその人種政策をめぐって政権から距離を置く方法を見つけました 。ベルリン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団とバイロイト・フェスティバルでの彼のパフォーマンスは、一度に帝国に仕え、それに反対しても、それを生き残ろうとする人々に助けを与えました。

「フルトヴェングラーのコンサートでは、私たちは皆、抵抗戦闘機の一つの家族になりました」と、ナチスの対戦相手の一人が言いました。

それにもかかわらず、ジョセフ・ゲッベルスは、フルトヴェングラーが「苦労する価値がある」と言ったように、ほとんど疑いを持っていませんでした。フルトヴェングラーは占領国での指揮を避けたが、例えば、1940年4月のドイツのノルウェー侵攻の1週間前にオスロでベルリン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団を率いた。彼はニュルンベルクの集会での実施を辞退したが、アンシュルスの直後の1938年にはウィーン国立歌劇場の勢力とともに、彼らの直前に現れ、満足していた。

フルトヴェングラーが困っている人に提供したであろうかなりの援助が何であれ、彼は汚された。彼が「悪魔の政権」を提供したカバーを考えると、エミグレの指揮者ブルーノ・ウォルターは、第二次世界大戦後に彼に尋ねました。

1936年にニューヨーク・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団と1949年にシカゴ交響楽団で行われたポストからの撤退を余儀なくされたとき、1954年に彼の死後、議論は激怒しました。

時間は距離、和解と研究をもたらしました。ミュージシャンはフルトヴェングラーの大義を取り上げ、ダニエル・バレンボイムが首位に立った。本は協力者を更に回復させた。フレッド・プリエバーグはフルトヴェングラーを「二重エージェント」と宣言し、もう一人はサム・シラカワが、まるでバトンを持つディートリッヒ・ボンホーファーであるかのように、ナチスを誰よりも阻止するためにもっと多くのことをしていると不条理に述べた。

録画後の録音が出現した - 主にアーカイブされたラジオ放送、特別な品質の一部。悲惨なことに、フルトヴェングラーは戦争中に彼の最も激しい先見の明を持っていたことが判明し、パージされたベルリン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団の舵取りでアーリア人の聴衆のために演奏しました。

しかし、これらの戦時中のテープは、フルトヴェングラーの謎に追加されただけです。彼が1942年3月にベルリンで与えた熱狂的なベートーヴェン第九は、音で焦げた抵抗の行為でしたか?それとも、1937年に言ったように、「ドイツ人の運命」は「統一不可能と思われるものを統一すること」であるという証拠でしたか?

「ドイツの音楽は証明する」と彼は続け、「ドイツ人は以前にそのような勝利を達成した」と続けていた。ヒトラーは明らかにそう思った。 フルトヴェングラー は、1ヶ月後に総統の誕生日のために交響曲を叱責するために操縦された後、ゲッベルスの手を振って撮影されました。

私たちの現在の気候にもかかわらず、誘惑は再びそれらに直面するのではなく、これらの困難を越えて移動するために残っています。それはワーナークラシックス、55 CDからの新しいセットの背後にある考え方のようです。

1969年に設立されたフランスの組織、ソシエテ・ヴィルヘルム・フルトヴェングラーの元副社長、ステファン・トパキアンの助けを借りてまとめられたこの箱は、ワーナーとユニバーサルのバックカタログの珍しい共有を表しています。 1926年のウェーバーとベートーヴェンのフルトヴェングラーの最初の臆病な録音から、1938年のチャイコフスキー・シックスや1951年のベートーヴェン・ナインスのような古典的なアカウントを通じて、彼は死の1ヶ月前にテーピングしたそびえ立つ「ダイ・ウォーキュール」までリスナーを連れて行きます。

ボックスに耳を傾け、マイクが 本当にフルトヴェングラーの 慎重にキャリブレーションされたダイナミクスと彼の深さから彼の音をキャプチャしたかどうか疑問に思っている場合は、あなたはまだ彼の有名な長い行の十分な、栄光の証拠を見つけます。あなたはまた、彼がしばしば記憶されている常に遅い、記念碑的な指揮者ではなかったことがわかります。彼の「ジークフリート・アイディル」には、ハイドンの繊細さと魅力、彼の活気に満ちたモーツァルトの尊厳に感動的な暖かさがあります。

全体を通して、リチャード・ワーグナーにさかのぼる指揮スタイルの世界が失われたのを聞く感覚があり、その意図的な不正確さと、そのテキストの詳細に関する音楽の背後にある知覚された精神の特権で、マエストロが今日行うのとは全く異なる何かを目指しています。

しかし、ワーナーの箱がそうではないのは、記録上の完全な フルトヴェングラー です。彼のディスコグラフィーは、メディアに対する彼の矛盾した態度と同様に、常に議論の対象となっていますが、ワーナーは彼のスタジオの努力と商業販売を明確に見て作ったライブ録音に限定されています。

不思議なことに、これらの基準は、フルトヴェングラーが1937年にロンドンで率いた「リング」の「ウォーキュール」や「ゲッテルダンメルン」のように、リリースしないことを決めた録音を含めることにつながっています。そして、1947年にシュトラウスの「メタモルフォセン」を通して彼の暴れを含む、以前ワーナーとユニバーサルのレーベルに登場したものでさえ、無数のライブ録音が取り残されています。1953年にイタリアのラジオのための彼の驚く「リング」。ブラームスの第3と第四の彼の破壊的な、取り乱した記述。そして彼の神秘的なブルックナーのほとんどすべて。

おそらく、いくつかのライブテープを除くすべてのテープを省略することは、フルトヴェングラーの人生の決定的な期間である戦争に2枚未満のディスクを捧えることを意味することを考えると、その決定はそれほど困惑していません。ノートに提供されたタイムラインは、現在の時制では、彼が戦時中に「彼の活動を制限する」と述べていますが、自分自身は「特定の公式イベントに参加する義務がある」と感じています。箱のキュレーターであるトパキアンは、ウィーンの戦後のベートーヴェン・セブンスはフルトヴェングラーを「彼の最も純粋な」ものにしているが、1942年のベルリンのアカウントの強さは「作品とは何の関係もない」と書いている。健忘症の中には、ここで遊んでる人もいます。

しかし、フルトヴェングラーは、音楽学者のロジャー・アレンが示したように、彼の保守的でナショナリズム的な世界観は、ワーナーボックスの録音のほとんどが行われた1945年以降でさえ、彼の指揮から決して分離不可能ではなかったと宣言しました。

1886年に考古学教授と画家の間に生まれたフルトヴェングラーは、自分をベートーヴェンと考えて待って育ちました。しかし、彼の初期の作曲のレビューは野蛮でした。彼は本格的に作曲に戻らなかった、歴史家クリス・ウォルトンは、ナチスの文化政策がモダニズムを破壊し、彼の間接的な、準ブルックネリアンの放浪のためのスペースを作った1930年代半ばまで、発見しました。

フルトヴェングラーは 指揮者のような抵抗に会わなかった。マンハイムでの一連のマイナーポストの後、彼は1922年にベルリン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団とライプツィヒ・ゲワントハウス管弦楽団の両方の首席指揮者となり、後にウィーン・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団とのライプツィヒの地位を落としました。

この期間を通して、 フルトヴェングラーは 今日不快な共鳴を持つ美学を打ち出しました。彼がドイツ美術の不屈の覇権を推進することは、たとえ彼が近代主義を憎んでいるにもかかわらずシェーンベルクを指揮したとしても、この大きな部分を占めていた。しかし、彼のスコア分析の方法、さらには彼の指揮理論は、ショーヴィニズム言語で表現されました。 彼は、音楽を禁止すべきではないと書いた - つまり、「ゴミやキッチュまたは反国家文化ボリシェヴィズムの明確なケースでない限り」

彼の挑戦のスタイルの台頭 - とりわけ彼のライバル、アルトゥーロ・トスカニーニのテキストの文字通り - ワイマール共和国は危機のドイツであることを彼のために確認しました。ナチスとの違いにもかかわらず、彼はほとんどの保守派と同様に、権威主義的なヴィルヘルミーヌの過去への復帰として彼らの買収を歓迎したようです。

フルトヴェングラーが1945年初めにドイツから逃れた後も、アルバート・スピアからの彼の安全に対する脅威の警告に続き、1946年の否定裁判でクリアされた後、この世界観は残った。1947年の後半、彼はまだドイツの交響曲の「有機的優位性」を称賛していました。2年後、彼はアトナリティの「生物学的不全」を否定した。

また、フルトヴェングラーは、音楽の力とその救世主としての彼の役割に関する壮大な主張から一歩も引き下がりませんでした。驚くべきことに、彼は1947年に同僚に「本当に偉大なドイツの楽曲の単一のパフォーマンスは、その性質上、すべての言葉よりもブーヘンヴァルトとアウシュビッツの精神のより強力で、より本質的な否定であった」と書くのが賢明だと考えました。

ワーナーの箱は、彼が彼のグラック序曲の痛みを伴う形式主義を含め、戦後に驚異を作ったことを明らかにします。シューマン第四の完全な啓示;天嵐の「フィデリオ」。そして1953年のレコーディング以来、卓越した「トリスタン・ウント・イゾルデ」。

しかし、 フルトヴェングラー が戦争の終結に向けて、彼がまだ「完全に切れ目のない国家」が生きていることを証明し、ベートーヴェン、ブラームス、ワーグナーを無傷で紛争を通して運んだという証拠だと主張するのはナイーブだったのと同じように、後の解釈を何らかの形で前に来たものとは何らかの形で切り離していると考えるのはナイーブだろう。

そして、フルトヴェングラーの遺産からの危険性は、今日でもクラシック音楽に残っている:彼が特異な天才を永続させた神話、ベートーヴェンやブラームスは、彼らの芸術とインパクトにおいて摩擦なく「普遍的」であるという考え、音楽が政治の上に永遠に浮かぶという偽の理想。彼自身は、ナチス党に加わったハーバート・フォン・カラヤンや、表彰台からヒトラーを称賛したカール・ベームよりも、私たちが道徳的に彼の多くを要求するフルトヴェングラーの芸術性の永続的な力を語っています。

歴史家のクリス・ウォルトンは、ナチスとの知的で美的な親和性のすべてを考えると、おそらく尋ねる質問は、以前のように、なぜ彼がドイツに滞在したのかではないと示唆しています。むしろ、ウォルトンが書いているように、「ナチスのモデルになる運命の」人物が書いているように、この男がそうではない理由かもしれません。その中で、彼と私たちのために、光の輝きが残っています。

おわり