きのうは道総研の鈴木大隆理事が司会進行されていた「気候風土適応住宅シンポジウム」を参観しておりました。伝統工法住宅というひとつの「建築文化」が存在して国、国交省などの住宅施策を推進するとき、そうした価値感を持つ作り手の人びとが、断熱性を最重視する施策をされることに危機感を持って声を上げるという現実がある。

そういった伝統工法派の人たちと国の対話集会のようなものに参加した経験もあり、そのときにもその「矢面」のような立場として北海道の鈴木大隆氏が正対していた。なにができるわけでもないけれど、一種応援する心理からそこに参加。伝統工法のみなさんの声に耳を傾けていた経験もある。しばらくそういう国の施策についてリアルタイム感を持っていなかったのだけれど、たまたま機会があってそのシンポジウムを拝聴させていただいた次第。

気候風土適応住宅という名称もはじめて知ったのだけれど、文脈的には伝統工法住宅についての国交省的な区分概念であるようです。国の省エネ基準義務化の動きなど住宅制度的なことがらについては自分自身の立場の変更もあったので、しばらく疎遠になっていた。久しぶりにそういった「現実リアルタイム」の空気感を認識していた。

というよりも「伝統工法住宅」というカテゴライズについてはわたし的には、民俗的な「家制度」というような部分との連関性で捉えていて、柳田國男的な解析の方向性の方にふかく興味を抱いていて、建築的な概念仕分けとして「伝統工法」について作り手のみなさんも必ずしも明瞭ではないのではないのだろうかと感じた。

北海道人としては積雪寒冷という絶対的な「気候風土」があって、そこで日本民族があらたな生存領域を模索していく中で住宅性能進化が促されたと思っている。そういうときに、しかし日本人としての家意識、「ご先祖さま」認識に代表されるような「民俗性」がどうなっていくか、その建築空間との相関性というテーマ意識だった。

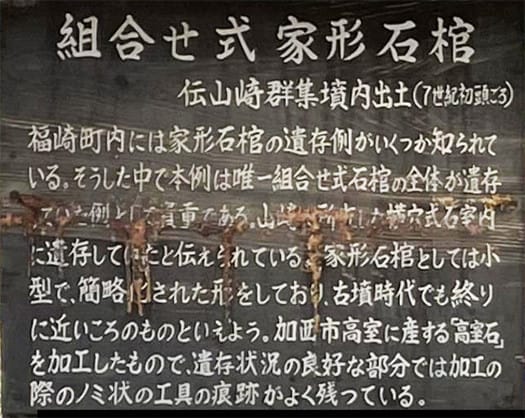

写真は兵庫県福崎町の柳田國男氏の「生家」に隣接してあった「家形石棺」。わたし的には「伝統工法とはなにか」という概念特定について、こういった石器・縄文にまで遡るような住文化概念が刷り込まれていたのだけれど、きのうの論議ではそういう展開はまったくなく、言ってみれば「木造架構の美感」「縁側空間でのコミュニケーション」というようなポイントが象徴の位置に挙げられていたように思った。

振り返って、わたし自身のNEXT領域としては、都市への人口集中と住宅性能進化という現代化要素と柳田國男的な「家・民俗」領域との相関関係を探ってみたいと再認識させられた。

写真のような家意識を寒冷地・北海道に暮らす日本人はどのように継承するのかというテーマ領域。そういう意味では大きな気付きの機縁を得られたと思っています。

English version⬇

The “house” as a folk custom and the traditional construction method “house”

What is the explicit “link” between Kunio Yanagida's “house” consciousness as a folk custom and traditional method houses? And can Japanese “folk customs” be created from Hokkaido? ...

Yesterday, I attended the “Climate-Adaptive Housing Symposium” chaired by Mr. Hirotaka Suzuki, Director of the Hokkaido Research Institute. When the national government and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism promote housing policies based on the existence of a certain “architectural culture” of traditional construction method houses, there is a reality that those who build houses with such values feel threatened by measures that place the highest priority on thermal insulation, and they raise their voices.

I had the experience of participating in a national dialogue meeting with such traditional construction method advocates, and at that time, Mr. Hirotaka Suzuki of Hokkaido was in front of me as the “arrowhead” of the discussion. Although I could do nothing about it, I participated in the meeting out of a kind of supportive mentality. I had the experience of listening to the voices of those involved in traditional construction methods. I have not been aware of such national policies in real time for a while, but I happened to have an opportunity to attend the symposium.

The name “climate-adaptive housing” is new to me, but it seems to be a Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism (MLIT) concept for traditional construction method housing. I have been away from the housing system for a while because of the change in my own position regarding the government's move to mandate energy conservation standards. It has been a while since I recognized such “real-time” atmosphere.

I am more interested in the direction of Yanagida Kunio's analysis, and I felt that the creators of “traditional construction method” as an architectural concept were not always clear about the “traditional construction method. I felt that the makers of these buildings were not always clear about the “traditional construction method” as an architectural conceptual classification.

As a Hokkaido native, I believe that the absolute “climate” of snowy and cold weather prompted the evolution of housing performance as the Japanese people searched for new areas of existence. In such a situation, however, I wondered what would happen to the Japanese sense of home, the “folklore” represented by the recognition of “ancestors,” and the correlation between this sense and architectural space.

The photo shows a “house-shaped sarcophagus” adjacent to Kunio Yanagida's “birth house” in Fukusaki Town, Hyogo Prefecture. I had been imprinted with this kind of concept of housing culture dating back to stone tools and the Jomon period, but there was no such development in yesterday's discussion, and instead, points such as “aesthetics of wooden structures” and “communication in the veranda space” were raised as symbols. I thought that the points of “aesthetics of wooden structure” and “communication in the porch space” were mentioned as symbolic points.

In retrospect, I was reminded of my own interest in exploring the correlation between the concentration of population in cities, the evolution of housing performance, and Kunio Yanagida's “house and folk customs” as a NEXT area.

This is the thematic area of how Japanese people living in the cold region of Hokkaido inherit a sense of home like the one in the photo. In this sense, I believe I have gained an opportunity for a great realization.