Meine Sache ~マイネ・ザッヘ~さんが、移民は少子化対策にはならない、と題して投稿しています。

大量移民とういのは、労働力確保、老人扶養、生活レベルの維持などの問題の解決策として導入されるようなのですが、その一方、先住民と移民との社会的緊張・摩擦などは常に問題になってきます。

そのもととなる調査報告、C.C.Howe Institute の報告書

結論的な部分だけさらっと見ますと

カナダの現状の移民受け入れ率だけでは、問題の解決にならず、また、解決できるほどのより一層の大量移民は非現実的であり、むしろ、定年を70才にするとか、出生率をあげる、生産性をあげる、といった対策の効果的ではないか、というわけです。

紹介されているもう一つの記事で指摘されていますが、日本の少子化問題というのは北朝鮮の核の脅威と同じくらい、日本の生存にとっては脅威となる問題なわけです。

自民党の一部からは大量移民が解決策として提示されましたが、こうした記事を読むと、どうもそれとてあまり頼りにならない。

優秀な外国人研究者などは多いに優遇すべきだとは思いますが、安易な大量移民は、解決よりもむしろ問題点の方が多いかも知れない。

まず、国民に過酷な現実を提示する必要があります。現状を維持すると、具体的にどうなるのか、それを知りたい。

そして、問題があれば、例えば、定年の延長、また、高齢者雇用差別の撤廃の徹底、そして、産めば産むほど得をするとまではいかずとも、2,3人くらいの子供がいる家族は、経済的に得するくらいの大胆な政策やら、少なくとも、そうした家族に全く負担がかからないような、大胆な子育て支援策などがあってもいいのではないか、と思う。

こうした試みをしてみて、それを補うために移民にも国民にも利益になるような移民政策を講じる。

移民は嫌、子育て支援のための犠牲は嫌では、日本の将来も暗澹たるものにならざるえない。

因みに、もう一つの記事の方では、他の点でも、日本などが引き合いに出されています。

Canada's big problem -- too few babies

By Leonard Stern, Times ColonistJuly 17, 2009

日本人のように便所に行く時間も惜しんで一日17時間も働けば生産性はあがるかもしれんが、それでは、家族に優しい環境とは言えまい、とーーどうも日本のサラリーマンというものに対して奇妙な固定観念があるようですが、移民先進国を引き合いに出して、ああはなりたくない、と嘆く日本人もいるのですがから、どっこいどっこいでしょう。

また、

子育ては支援は、出生率上昇に消極的には貢献しても積極的に子供を産む動機にはならない、と指摘し、出生率をあげる確実な方法ーーー著者は反対するといっていますがーーーー女性の教育やら社会的進出の機会を奪って、子育てに専念させ、男女平等を否定することだ、といっています。

男女平等の観念が蔓延して女性が企業・社会に進出したのか、経済構造により女性が企業・社会に進出せざるえなくなったのか、あるいは、それらが影響しあって、並行しているのかは、定かではありませんが、伝統的な男女の役割を選択するにせよ、男女ともに経済的稼ぎ手になって男女とも子育てに均等な役割を担うにせよ、働きながら子供をもっても、少なくとも経済的な負担にはならない、という政策は必須ではないでしょうか?

大量移民とういのは、労働力確保、老人扶養、生活レベルの維持などの問題の解決策として導入されるようなのですが、その一方、先住民と移民との社会的緊張・摩擦などは常に問題になってきます。

そのもととなる調査報告、C.C.Howe Institute の報告書

結論的な部分だけさらっと見ますと

Faster, Younger, Richer?

The Fond Hope and Sobering Reality of

Immigration’s Impact on Canada’s Demographic

and Economic Future

Robin Banerjee

William B.P. Robson

In this issue...

More and younger immigrants cannot, on their own, offset the impact

of low past fertility on Canadian workforce growth, old-age

dependency, and incomes per person. Later retirement, higher fertility,

and faster productivity growth are more powerful tools to ease the

stress of demographic change on Canadian living standards.

More and younger immigrants cannot, on their own, offset the impact

of low past fertility on Canadian workforce growth, old-age

dependency, and incomes per person. Later retirement, higher fertility,

and faster productivity growth are more powerful tools to ease the

stress of demographic change on Canadian living standards

Conclusion

The message of these simulations is that we should not overstate the contribution immigration can

make to maintaining workforce growth, keeping Canada young and boosting living standards.

Workforce growth is the easier of the two demographic variables to address with immigration.

Even so, immigration rates equal to 1 percent of the already resident population would not prevent

Canada’s workforce growth dipping to historic lows in the 2020s. Furthermore, the immigration levels required – even with major efforts to attract a larger share of younger people – to maintain workforce growth at current rates would be well outside the realm of economic or political feasibility. An aging population is an even more difficult challenge. Increasing immigration to 1 percent of population per year without varying its age distribution would slow the rise in the OAD ratio only marginally. And raising immigration to this level while recruiting younger immigrants aggressively would still not prevent an historic rise in the ratio. Only extreme and unpalatable policies, such as rapidly increasing immigration to well over 3 percent for decades could come close to stabilizing the OAD ratio. Per-person income growth is the most difficult target of all. The inescapable consequence of larger numbers of arrivals is a larger population among which to share any resulting increase in aggregate output. Even very large changes in immigration flows or extreme policies to shift the age-structure of immigrants cannot affect future growth of income per person by more than a few tenths of a percentage point. Furthermore, attempts to maintain per-person income growth at historic rates through immigration alone produce preposterous population numbers. Indeed, the contrast between the projected populations for Canada in the final year of the projections illustrates vividly how weak a tool immigration is, on its own, to decisively shape Canada’s demographic and economic future. If Canadians are prepared for major policy reforms to mitigate the impact of a slower-growing and aging population on Canada’s workforce, age structure and income growth, other tools have – at least in a numeric sense – at least as much promise as immigration. Delaying the normal age of retirement can help both workforce growth and the OAD ratio in the near term. Higher fertility would help achieve both goals in the next generation and beyond, and faster productivity growth will do more for real income growth than any conceivable immigration strategy. Even if Canadians do choose higher immigration, and even if they choose to target younger immigrants for demographic reasons, such measures need to be complemented with other policies to delay retirement, raise fertility and boost productivity if Canada truly wishes to transform its demographic and economic future.

カナダの現状の移民受け入れ率だけでは、問題の解決にならず、また、解決できるほどのより一層の大量移民は非現実的であり、むしろ、定年を70才にするとか、出生率をあげる、生産性をあげる、といった対策の効果的ではないか、というわけです。

紹介されているもう一つの記事で指摘されていますが、日本の少子化問題というのは北朝鮮の核の脅威と同じくらい、日本の生存にとっては脅威となる問題なわけです。

自民党の一部からは大量移民が解決策として提示されましたが、こうした記事を読むと、どうもそれとてあまり頼りにならない。

優秀な外国人研究者などは多いに優遇すべきだとは思いますが、安易な大量移民は、解決よりもむしろ問題点の方が多いかも知れない。

まず、国民に過酷な現実を提示する必要があります。現状を維持すると、具体的にどうなるのか、それを知りたい。

そして、問題があれば、例えば、定年の延長、また、高齢者雇用差別の撤廃の徹底、そして、産めば産むほど得をするとまではいかずとも、2,3人くらいの子供がいる家族は、経済的に得するくらいの大胆な政策やら、少なくとも、そうした家族に全く負担がかからないような、大胆な子育て支援策などがあってもいいのではないか、と思う。

こうした試みをしてみて、それを補うために移民にも国民にも利益になるような移民政策を講じる。

移民は嫌、子育て支援のための犠牲は嫌では、日本の将来も暗澹たるものにならざるえない。

因みに、もう一つの記事の方では、他の点でも、日本などが引き合いに出されています。

Canada's big problem -- too few babies

By Leonard Stern, Times ColonistJuly 17, 2009

It's true, for example, that by working insanely hard, the Japanese are able to maintain high productivity despite their low fertility rate. But a 17-hour work day in a Tokyo cubicle, where you feel guilty taking bathroom breaks, is hardly a family-friendly environment. Japan is committing suicide by creating a culture littered with disincentives to childbearing.

日本人のように便所に行く時間も惜しんで一日17時間も働けば生産性はあがるかもしれんが、それでは、家族に優しい環境とは言えまい、とーーどうも日本のサラリーマンというものに対して奇妙な固定観念があるようですが、移民先進国を引き合いに出して、ああはなりたくない、と嘆く日本人もいるのですがから、どっこいどっこいでしょう。

また、

So how do we get western women to have more children? There's evidence that accessible child care and similar supports are a big help. But even free daycare might not constitute an "incentive" to have children. At most, it represents the elimination of an obstacle.

The brutal truth is this: The only surefire way to ensure women have lots of children is to deny them sexual equality. (Needless to say, this is an approach I'd oppose.)

Equality has meant giving women opportunities for personal fulfilment beyond childrearing. It has meant that for women, social status is now derived from the same things as for men -- educational achievement, professional advancement, accumulation of wealth.

子育ては支援は、出生率上昇に消極的には貢献しても積極的に子供を産む動機にはならない、と指摘し、出生率をあげる確実な方法ーーー著者は反対するといっていますがーーーー女性の教育やら社会的進出の機会を奪って、子育てに専念させ、男女平等を否定することだ、といっています。

男女平等の観念が蔓延して女性が企業・社会に進出したのか、経済構造により女性が企業・社会に進出せざるえなくなったのか、あるいは、それらが影響しあって、並行しているのかは、定かではありませんが、伝統的な男女の役割を選択するにせよ、男女ともに経済的稼ぎ手になって男女とも子育てに均等な役割を担うにせよ、働きながら子供をもっても、少なくとも経済的な負担にはならない、という政策は必須ではないでしょうか?

少子高齢化の問題について、先進諸国では様々な対策が採られていますが、高齢者福祉が「若年者福祉」よりもずっと優遇されている場合には、出生率向上に失敗しがちであるという見方もあるようです。

あと人々の高学歴志向も、結果として子供の養育費用を押し上げ、子供を多くは持てないと考える人を増やしているようです。ここら辺の個人の意識改革も欠かせないように思います。

日本人の年間労働時間は公式には北米並となっているようですね。サービス残業がなければの話だそうですが。

人口問題は、もしかしたら、上記論者がいうように、日本にとって北朝鮮の脅威、あるいはそれ以上に深刻な問題かもしれないので、まず、問題は何なのか、官僚なり政治家なりにしっかりと提示してもらいたいです。

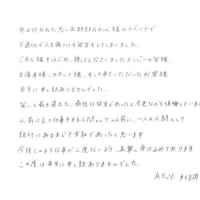

ご意見ありがとうございます。

しかし、少子高齢化問題というのは、既に対策の時期を逸してしまったかも知れませんね。私のサイトで日本の主要都市の年齢別人口グラフを紹介していますが、地方は特に悲惨な状況になっています。

わざと国民を貧困化しているとまでは、いいませんけど、政治家の無策、そして、経済界の要請・思惑で、結果的に安易な移民政策で労働力の不足を補うじゃないか、思いますね。