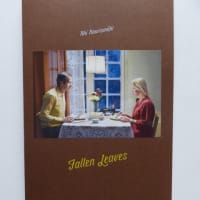

ケン・ローチ監督の作品が好きで、これまでいろいろと観てきました。いまだに階級意識が残るイギリスにあって、ローチ監督の映画の登場人物はたいてい労働者階級に属する人たちで、厳しい現実の中でもがきながら生きる人びとを描いてきた。今回も育った環境のせいでケンカを繰り返す青年を主人公に物語は展開するが、いつもとちょっと違いラストがとてもハートフルだ。

恋人の出産が間近だというのにケンカのトラブルを起こしたロビーは、刑務所送りの代わりに社会奉仕活動を命じられる。そこで出会った指導者のハリーは、赤ん坊の誕生を上等なウィスキーで祝ってくれ、恋人と息子との生活を手放さないよう諭す。ハリーはロビーと3人の仲間をウィスキー蒸留所に連れて行ってくれるが、それがきっかけでロビーの眠っていた“テイスティング”の才能が目覚め始める。ある日、100万ポンドもする樽入りのウィスキーのオークションの話を耳にしたロビーは、仲間たちと大勝負に出る。

恋人と息子と父親のようなハリーの存在が、荒んでいたロビーを変えてくれた。“天使の分け前”とは、ウィスキーなどが樽の中で醸成される間に年2%ほど蒸発して失われる分のことを言うが、なんてウィットに富んで心が優しくなる言葉だろう。映画のラストでロビーはハリーに素敵な“天使の分け前”をプレゼントするが、それを手にしたハリーの笑顔は幸せそのものだ。

ウィスキー蒸留所やエジンバラ、グラスゴー、その他のスコットランドの美しい景色が楽しめる。男性はキルトを着用するとき下着を穿かないって本当だったのだなど、笑えるシーンもある。ただ、100万ポンドのウィスキーの香りと味をスクリーンの外では味わえないのが残念。(久)

原題:THE ANGEL'S SHARE

監督:ケン・ローチ

脚本:ポール・ラヴァティ

出演:ポール・ブラニガン、ジョン・ヘンショー、ガリー・メイトランド、ウィリアム・ルアン

恋人の出産が間近だというのにケンカのトラブルを起こしたロビーは、刑務所送りの代わりに社会奉仕活動を命じられる。そこで出会った指導者のハリーは、赤ん坊の誕生を上等なウィスキーで祝ってくれ、恋人と息子との生活を手放さないよう諭す。ハリーはロビーと3人の仲間をウィスキー蒸留所に連れて行ってくれるが、それがきっかけでロビーの眠っていた“テイスティング”の才能が目覚め始める。ある日、100万ポンドもする樽入りのウィスキーのオークションの話を耳にしたロビーは、仲間たちと大勝負に出る。

恋人と息子と父親のようなハリーの存在が、荒んでいたロビーを変えてくれた。“天使の分け前”とは、ウィスキーなどが樽の中で醸成される間に年2%ほど蒸発して失われる分のことを言うが、なんてウィットに富んで心が優しくなる言葉だろう。映画のラストでロビーはハリーに素敵な“天使の分け前”をプレゼントするが、それを手にしたハリーの笑顔は幸せそのものだ。

ウィスキー蒸留所やエジンバラ、グラスゴー、その他のスコットランドの美しい景色が楽しめる。男性はキルトを着用するとき下着を穿かないって本当だったのだなど、笑えるシーンもある。ただ、100万ポンドのウィスキーの香りと味をスクリーンの外では味わえないのが残念。(久)

原題:THE ANGEL'S SHARE

監督:ケン・ローチ

脚本:ポール・ラヴァティ

出演:ポール・ブラニガン、ジョン・ヘンショー、ガリー・メイトランド、ウィリアム・ルアン

The background of The Angels' Share, his latest collaboration with the leftwing Scottish lawyer turned screenwriter Paul Laverty, is the widespread, seemingly permanent youth unemployment and the despair and communal erosion it engenders. But the realistic and humanistic tone is bracingly optimistic, and it's one of the 75-year-old Loach's sprightliest films, made at an age when most directors have hung up their viewfinders, entered a period of terminal decline or settled for repeating themselves.

The movie begins with a group of criminals brought together by chance in the manner of The Usual Suspects and gradually modulates into a heist comedy that combines two classic Scottish films, both directorial debuts from different eras, Alexander Mackendrick's Whisky Galore! (1949) and Bill Forsyth's That Sinking Feeling (1980).

The young offenders, played by non-professional actors who perform brilliantly under Loach's sympathetic direction, are introduced at Glasgow's City Court when pleading guilty to a variety of crimes. Their demeanour is playfully contrasted with the solemnity of the bewigged judge, and most of the offences are quite minor – petty theft, defacing public statues, drunkenness in a public place. However, one of the defendants, Robbie (Paul Brannigan), is up for grievous bodily harm, and he's only saved from another custodial sentence because his girlfriend is eight months pregnant.

All of them are given community service and are fortunate to come under the supervision of Harry (John Henshaw, a familiar face from TV drama and the occasional movie), a middle-aged, working-class Mancunian who forges a bond with Robbie. He's as sympathetic a figure as Colin Welland's teacher in Kes and Peter Mullan's soccer coach in My Name is Joe and brings a wealth of unpatronising understanding to his charges' lives and problems. The unemployed Robbie, determined to go straight and be a good father, appears to have everything against him – a history of violence (there's a revealing razor scar on his left cheek) and his girlfriend's brutal father, who's determined to get him out of Glasgow and away on his own, whether by force or bribery. Harry could be his salvation.

At this point a major dramatic and thematic device appears to link the action, the humour and the ironic morality, and it's whisky. Harry is a connoisseur of fine single malt. He pours a dram to celebrate Robbie's fatherhood. He takes the group of offenders, who are doing public service, painting old community centres and cleaning cemeteries, on a tour of a distillery and then to a whisky tasting in Edinburgh. These occasions constitute a delightful documentary on scotch, its history, production and consumer appreciation. By revealing that Robbie has a natural nose for the hard stuff, it also leads to his discovery of a vocation, his return to crime and his ultimate redemption.

In Whisky Galore! some Scottish villagers help themselves when a whisky-laden merchant ship is wrecked on their shores. In That Sinking Feeling some unemployed teenagers in a desolate late 1970s Glasgow plan the robbery of a warehouse containing stainless steel sinks. Crime is not new in Loach's work, and characters in past films, though not explicitly here, clearly believe in the dictum of the French anarchist and social reformer Pierre-Joseph Proudhon that property is theft. They rustle sheep, rob a sporting goods van to equip their football team with strips, make away with the grass from the bowling green of (naturally) a Conservative club.

The impenetrable script aside, The Angels’ Share is a peculiar cinematic brew that combines Loach’s long-standing commitment to the British underclass with a frothy, more conventional caper scenario. Gradually, the dark, peppery bite of the former is eclipsed by the creamy taste of the latter. It’s as though Loach set out to make pure, whimsical comedy, but couldn’t fully renounce his roots in left-leaning political activism. The result is a sometimes gritty, occasionally charming Highland hybrid, but the final balance feels slightly off-kilter.

The focus of the social-conscience element is Robbie (Paul Brannigan, making his film debut), a yob seemingly trapped in a cycle of youthful violence. His girlfriend’s family despises him, and he’s the target of a menacing gang of street thugs.

Fortuitously spared a jail sentence for his latest brawl (because he is about to become a first-time father), he joins a cadre of other misfits in menial public service – cleaning graveyards and painting run-down community centres.

As part of his penance, he agrees to meet with a young man (and his family) whom he brutally beat in a drunken, unprovoked rage, leaving the victim blind in one eye. Robbie absorbs their justified vitriol with silent tears. It’s the film’s most memorable and affecting scene.

One day, Harry (John Henshaw), the cadre’s sympathetic overseer, escorts the group on a tour of an area distillery. There, Robbie suddenly demonstrates a discriminating palate for Scotch, and a nose with an uncanny penchant for more than mayhem.

That previously unknown native talent lays the groundwork for the ensuing caper: Robbie and the reforming gang’s improbable plan to siphon four bottles’ worth of an extremely rare single malt that another Scottish distillery is putting up for auction. This, ostensibly, is to be their angel’s share (hence the film’s title), the equivalent of the 2 per cent of Scotch whisky said to evaporate from every cask.

You know Loach has begun tripping into fantasy land when the million-pound-plus cask of vintage hootch is left virtually unsecured overnight, essentially asking to be stolen.

What does succeed is the cast, particularly Henshaw as the avuncular supervisor and Brannigan, a novice actor whose own youth is said to have mirrored that of Robbie’s. He’s entirely credible in the part, his softer side always at the mercy of his well-honed, ruffian, survival reflexes.

But the film’s moral calculus is perplexing. We clearly want to applaud Robbie’s attempt to escape the rough hand that life has dealt him. But we are asked to do so by sanctioning what is, after all, theft, and evidence that Robbie’s solemn pledge to reform is essentially hollow. So what is Loach’s point – that crime is permissible if victimless? Or (nudge, nudge) tolerable in this case because only the rich auction winner and the corporate distillery owners will suffer?

That, perhaps, is the core problem: What’s a heist film without a heist? So Robbie has to orchestrate the adventure, automatically forfeiting any claim to genuine rehabilitation. A cleverer third act would have found a way for him to use his nose to win another way.