久しぶりにメールをのぞいていたら、ドアブロからのメールが沢山たまっていて、その中の一つ

北の国から猫と二人で想う事 livedoor版

2011年08月24日 歴史、史実、記録 中国チベット台湾韓国北朝鮮周辺

「一番公正な歴史教科書は日本」米スタンフォード大学

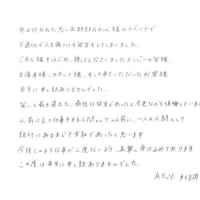

(クリック拡大)

なお読売記事は2010年のもの

というわけで、

Divided Memories and Reconciliationのなかの

Downloads

+PDF+

Divided Memories and Reconciliation: A Progress Report

文書は2008年のものである。

飛ばし読み。

歴史にせよ全く中立の観点からの記述というのはありえない。その意味でこのスタンフォードの文書も一つの視点=偏見からみられているとは思うが、しかし、わりに多視点であるという意味では公正である。多視点が提供されていない、という意味では日本の歴史教科書が公正というわけではない。

各国、歴史的事実よりも、それを語る語彙、あるいはそれを編集した物語に特徴がある。

英語圏で日本の歴史教科書は自国礼賛主義だと勘違いしている論者には啓蒙的かもしれない。参考にされたい。

ちょっと抜き書き・・・

北の国から猫と二人で想う事 livedoor版

2011年08月24日 歴史、史実、記録 中国チベット台湾韓国北朝鮮周辺

「一番公正な歴史教科書は日本」米スタンフォード大学

(クリック拡大)

なお読売記事は2010年のもの

というわけで、

Divided Memories and Reconciliationのなかの

Downloads

+PDF+

Divided Memories and Reconciliation: A Progress Report

文書は2008年のものである。

飛ばし読み。

歴史にせよ全く中立の観点からの記述というのはありえない。その意味でこのスタンフォードの文書も一つの視点=偏見からみられているとは思うが、しかし、わりに多視点であるという意味では公正である。多視点が提供されていない、という意味では日本の歴史教科書が公正というわけではない。

各国、歴史的事実よりも、それを語る語彙、あるいはそれを編集した物語に特徴がある。

英語圏で日本の歴史教科書は自国礼賛主義だと勘違いしている論者には啓蒙的かもしれない。参考にされたい。

ちょっと抜き書き・・・

・・・・・Shaping national identity remains the goal of history textbooks today, especially in countries where the national state is directly involved in their writing, production and/or approval. Textbooks are organized around the story of a nation or people, and curriculum guides explicitly stipulate the building of national identity as a primary goal of the history curriculum. The current Korean current guideline for first year high school history courses, for example, asserts that

“The mission of Korean history is, through a revealing of the real nature of our national spirit and life, to establish our nation’s true character. In other words, through the study of history, a student is able to affirm our nation’s traditions, and they can pro-actively participate in the spreading of the proper understanding of our national history.” These goals are echoed in other East Asian countries, with the possible exception of Japan, where emphasis is also placed on efforts to “develop friendly and cooperative relations with neighboring countries and to contribute to the peace and stability of Asia, and, in turn, of the world.”

・・・・・

U. S Textbooks: A National Bildungsroman

The narrative of war presented in The American Pageant reminds one of those eighteenth century novels in which a naïve young hero, after making many mistakes and encountering many disappointments, finally achieves wisdom. It is a story of “awakening” or “enlightenment” ―the story of a country maturing to its responsibilities as a world power. The narrative begins in the 1930s with a naive America that recoils from engagement with the outside world, and it ends in the 1940s with an America that is challenged by a world full of new dangers but willing to face up to them. The war itself, the middle chapter of the story, provides the experience that catalyzes the change. The ultimate lesson to be learned from this history is that Americans must remain vigilant toward threats from the outside world and that they must react to them in a timely fashion.

・・・・・

Chinese Textbooks: Narratives of Resistance and Liberation

War stories in Chinese textbooks are not about “awakening” or “maturing” ; they are about “struggle,” “resistance,” and “liberation.” They tell a tale of two wars: the national resistance against Japanese aggression and the internal conflict between the GMD and the CCP. Inevitably the two wars are linked, not only because they occur simultaneously, but because the outcome of the anti-Japanese war is seen as a major influence on the outcome of the civil war. Chinese war stories also come in two versions, one written in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the other in the Republic of China (ROC). Both agree that the defeat of the Japanese ended a century of national humiliation and established China as an international power, but the path to victory is described differently and so is the outcome. Finally, to complicate matters, both the PRC and the ROC textbooks have undergone significant revisions in the past decade―with significant changes in emphasis.

The common element in all Chinese textbooks is the long-term historical significance of the war. Indeed, the language used to describe the outcome of victory, though not identical, is similar. The 2007 ROC text observes: “China endured eight years of the anti-Japanese war and finally became a victorious state in the second world war. This greatly compensated for the loss of national dignity from the second half of the nineteenth century onward. Not only did nationalism swell, China’s position in the international arena was also significantly elevated.” (189) Similarly the 2003 PRC textbook observes: “The Chinese victory in the anti-Japanese war was at the time the first complete success that the Chinese people achieved in fighting against foreign invaders in more than 100 years. It greatly strengthened Chinese national pride and confidence among people all over the country . . . The Chinese people’s resistance against the Japanese made a great contribution to the victory of the world anti-fascist war. The international status of China was raised.” (46) In the broadest sense, all the Chinese history textbooks offer a triumphal narrative that celebrates the return of China to the position of a major world power.

Interestingly, both the ROC and the PRC textbooks suggest that the Chinese achieved victory against the Japanese without much outside help, or at least without much help in the early days of the conflict.

・・・・・

Japanese Textbooks: History Without a Story?

In contrast to American and Chinese textbooks Japanese history textbooks offer no strong narrative about the war. This is surprising given that many different war stories circulate in Japan’s public discourse and popular culture: as a war of aggression that did great damage to the peoples; as a war for the liberation of Asia from Western colonialism; as a war fought by heroic but doomed soldiers; as a war that the Japanese people themselves “victims”; and so forth. None of these stories find their way into the Japanese textbooks in undiluted form. Compared to the American and Chinese history textbooks their tone is muted, neutral, and almost bland. Perhaps it is this affectless neutrality that so infuriates not only the Japanese right-wing but also Chinese and Korean critics. The Japanese history textbooks do not tell the stories that they want to hear―or are used to hearing.

The Japanese textbooks make no attempt to glorify or justify the war, to portray Japan as the “victim” of outside forces, or to offer an apologia for wartime atrocities. Nor do they absolve the Japanese civilian public of supporting the war effort. If there is an overarching narrative in the Japanese textbooks it is almost a Biblical tale of sin, redemption and recovery. Although the Yamakawa 2002 textbook is almost totally bereft of any explicit interpretation, it can be read as the story of how a peaceful, prosperous and democratic Japan emerging in the 1920s is led astray in the 1930s by a military pursuing a policy of aggression that results in national disaster, then emerges chastised by defeat and transformed by postwar reform to become a peaceful member of the world order. This story what Japanese historians on the left used to call the “Kennedy-Reischauer line” or simply “the Reischauer line.” But since the Yamakawa text so egregiously avoids judgment or emotion it would be more accurate to say that its narrative conveys a simple message: the folly and failure of militaristic expansion.

・・・・・

Finally, in contrast to the United States and China, Japan is a country where nationalism (pride in national culture and accomplishments) may be very strong but patriotism (willingness to die for the nation) is very weak. Indeed, a recent international comparative survey found that the willingness of youth to fight for their country is highest in countries like the PRC and ROK and lowest in Japan. The “love of country” found in “normal nations” has not taken root in a Japan that has become (as General Mac Arthur hoped) a “Switzerland of Asia” ―peaceful, prosperous, complacent, and armed but passively defensive. Having experienced a disastrous defeat, the Japanese public, much to the onsternation of some of their leaders, remains pacifist in orientation. The content of Japanese history textbooks is entirely consistent with that orientation.

・・・・・