Austerity's Grim Legacy

(緊縮政策の残酷な遺産)

Paul Krugman

NYT:NOV. 6, 2015

(緊縮政策の残酷な遺産)

Paul Krugman

NYT:NOV. 6, 2015

When economic crisis struck in 2008, policy makers by and large did the right thing. The Federal Reserve and other central banks realized that supporting the financial system took priority over conventional notions of monetary prudence. The Obama administration and its counterparts realized that in a slumping economy budget deficits were helpful, not harmful. And the money-printing and borrowing worked: A repeat of the Great Depression, which seemed all too possible at the time, was avoided.

経済危機が2008年に起こった時、政策立案者は多かれ少なかれ正しいことをやりました。

FRBなどの中銀は、金融システムのサポートは慎重な金融政策という従来の概念に優先する、ということに気付きました。

オバマ政権や各国政府は、不景気においては財政赤字は毒よりも薬になる、ということに気付きました。

そして紙幣増刷と借入は機能しました。

当時は余りにもありそうに見えた大恐慌の再発は回避されました。

Then it all went wrong. And the consequences of the wrong turn we took look worse now than the harshest critics of conventional wisdom ever imagined.

そして、全て調子が狂いました。

また、僕らが犯した過ちの結末は今や、従来の概念に対する最も厳しい批判者がこれまでに想像したよりも酷い様相を呈しています。

For those who don't remember (it's hard to believe how long this has gone on): In 2010, more or less suddenly, the policy elite on both sides of the Atlantic decided to stop worrying about unemployment and start worrying about budget deficits instead.

覚えていない人々のために記しますが(これがこんなに長く続いているとは…)、2010年、殆ど突然、大西洋の両岸の政界幹部は失業について心配するのを止めて、その代わりに財政赤字を心配し始めると決断しました。

This shift wasn't driven by evidence or careful analysis. In fact, it was very much at odds with basic economics. Yet ominous talk about the dangers of deficits became something everyone said because everyone else was saying it, and dissenters were no longer considered respectable — which is why I began describing those parroting the orthodoxy of the moment as Very Serious People.

このシフトの原動力は証拠でも慎重な分析でもありませんでした。

実は、基本的な経済学とかなり矛盾するものでした。

しかし財政赤字の危険に関する脅かすような話を、他の人が皆そう言っているからという理由で誰もがするようになり、反対する人はもうまともだと思われなくなりました。

だからこそ僕は、時の通説を繰り返す人々をとてもシリアスな人達と評し始めたのです。

Some of us tried in vain to point out that deficit fetishism was both wrongheaded and destructive, that there was no good evidence that government debt was a problem for major economies, while there was plenty of evidence that cutting spending in a depressed economy would deepen the depression.

財政赤字フェチは間違っている上に破壊的だ、政府の借金が先進国にとって問題になっているという明白な証拠は一つもない、その一方で不景気の時に支出を削減することで不況が悪化するという証拠は掃いて捨てるほどある、と指摘する無駄骨を折った者も僕らの中にはいました。

And we were vindicated by events. More than four and a half years have passed since Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles warned of a fiscal crisis within two years; U.S. borrowing costs remain at historic lows. Meanwhile, the austerity policies that were put into place in 2010 and after had exactly the depressing effects textbook economics predicted; the confidence fairy never did put in an appearance.

そして、事態が僕らの正しさを証明してくれました。

アラン・シンプソン氏とアースキン・ボウルズ氏が2年以内に財政危機が来るぞと警告してから、4年半以上が過ぎました。

米国の借入金利は歴史的に低い水準に留まっています。

一方、緊縮政策は2010年に実施され、その後、経済学の教科書が予測した通りの景気後退的な影響をもたらしました。

信頼の妖精は決して現れませんでした。

Yet there's growing evidence that we critics actually underestimated just how destructive the turn to austerity would be. Specifically, it now looks as if austerity policies didn't just impose short-term losses of jobs and output, but they also crippled long-run growth.

しかし、僕ら批判者が緊縮政策がどれほど破壊的かを実は甘く見ていたという証拠は増え続けています。

とりわけ今では、緊縮政策は雇用と生産に短期的な損失をもたらしただけでなく、長期的な成長率まで損なったように見受けられます。

The idea that policies that depress the economy in the short run also inflict lasting damage is generally referred to as "hysteresis." It's an idea with an impressive pedigree: The case for hysteresis was made in a well-known 1986 paper by Olivier Blanchard, who later became the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, and Lawrence Summers, who served as a top official in both the Clinton and the Obama administrations. But I think everyone was hesitant to apply the idea to the Great Recession, for fear of seeming excessively alarmist.

短期的に景気を悪くする政策は長期的なダメージももたらす、という考えは一般的に「ヒステリシス」と呼ばれています。

これは目を見張る血統を持つ考えです。

ヒステリシスは、その後IMFのチーフ・エコノミストになられたオリヴィエ・ブランチャード教授と、クリントン政権、オバマ政権の両方で高官を務めたラリー・サマーズ教授が1986年に発表した有名な論文の中で論証されています。

しかし僕は、過剰に騒いでいるように見えるのを恐れて、皆この考えを大不況に適用するのを躊躇したのだと思っています。

At this point, however, the evidence practically screams hysteresis. Even countries that seem to have largely recovered from the crisis, like the United States, are far poorer than precrisis projections suggested they would be at this point. And a new paper by Mr. Summers and Antonio Fatás, in addition to supporting other economists' conclusion that the crisis seems to have done enormous long-run damage, shows that the downgrading of nations' long-run prospects is strongly correlated with the amount of austerity they imposed.

しかし現時点において、証拠はヒステリシスだと叫んでいるようなものです。

米国のようにほぼ回復したかのような国ですら、危機前の予測で現時点で至っているはずの状態よりも遥かに貧しいのです。

また、サマーズ教授とアントニオ・ファタス教授による新しい論文は、今回の危機は著しい長期的ダメージをもたらしたようだ、とする他のエコノミストの結論を支持するのに加えて、各国の長期見通しの下方修正はそれらの国が実施した緊縮政策の度合いと強い相関性があると示しています。

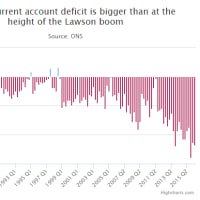

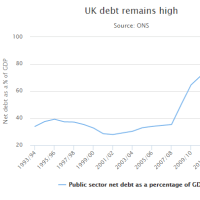

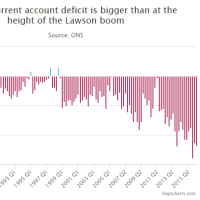

What this suggests is that the turn to austerity had truly catastrophic effects, going far beyond the jobs and income lost in the first few years. In fact, the long-run damage suggested by the Fatás-Summers estimates is easily big enough to make austerity a self-defeating policy even in purely fiscal terms: Governments that slashed spending in the face of depression hurt their economies, and hence their future tax receipts, so much that even their debt will end up higher than it would have been without the cuts.

これが示唆しているのは、緊縮政策に頼ることは全く壊滅的な効果があり、2-3年間に亘る雇用と所得の減少を遥かに上回るということです。

実際、ファタス・サマーズ論文で試算されている長期的なダメージは、緊縮政策を純粋に財政面だけでも自滅的政策にするほどの規模とされています。

不況を前に支出を削減した政府は経済を傷付け、それによって将来の税収を損ない、それによって支出削減をやらなかった場合よりも沢山の借金を抱える羽目に陥りました。

And the bitter irony of the story is that this catastrophic policy was undertaken in the name of long-run responsibility, that those who protested against the wrong turn were dismissed as feckless.

また、この話の厳しい皮肉は、この破滅的な政策が長期的な責任の名の下に実施されたということ、間違いに抗議した人々を無責任呼ばわりしたことです。

There are a few obvious lessons from this debacle. "All the important people say so" is not, it turns out, a good way to decide on policy; groupthink is no substitute for clear analysis. Also, calling for sacrifice (by other people, of course) doesn't mean you're tough-minded.

この大失敗には幾つか明らかな教訓があります。

「重要人物全員がそう言っている」というのは良い政策決定方法ではないとわかりました。

集団思考は明確な分析の代替にはならないのです。

また、犠牲を(勿論、他人に)求めることは、あなたは意志が強いという意味ではありません。

But will these lessons sink in? Past economic troubles, like the stagflation of the 1970s, led to widespread reconsideration of economic orthodoxy. But one striking aspect of the past few years has been how few people are willing to admit having been wrong about anything. It seems all too possible that the Very Serious People who cheered on disastrous policies will learn nothing from the experience. And that is, in its own way, as scary as the economic outlook.

とはいえ、この教訓は浸透するのでしょうか?

過去の経済問題(1970年代のスタグネーションなど)は、経済の通説を広く再考させました。

しかし過去2-3年で驚くべきは、何かについて間違っていたと認める気のある人々が極少数だということです。

破滅を招く政策を拍手喝采したとてもシリアスな人達がこの経験から何も学ばない、ということも大いにありそうです。

また、それ独自の形で、経済展望と同じ位恐ろしいことです。