The world economy:Inflation's back

(世界経済:インフレ復活)

The Economist:May 22nd 2008

(世界経済:インフレ復活)

The Economist:May 22nd 2008

Double-digit price rises are about to afflict two-thirds of the world's population

二桁台の価格上昇は、世界の人口の2/3に影響

RONALD REAGAN once described inflation as being “as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit-man”. Until recently, central bankers thought that this thug had been locked up for life. Thanks to sound monetary policies, inflation worldwide had stayed low in recent years. But the mugger is back on the prowl.

ロナルド・レーガンはかつてインフレを「強盗のように乱暴で、銃を持った強盗のように恐ろしくて、暗殺者ぐらいに死人が出る」と評した。

最近まで中央銀行マンは、このチンピラが終身刑に服していると思っていた。

しっかりした金融政策のおかげで、世界中のインフレは近年低い水準に留まっていた。

だが、チンピラは再びうろつき始めたのである。

Even though America is close to recession and growth in other developed economies has slowed, inflation is rising. Jean-Claude Trichet, president of the European Central Bank, this week gave warning about the mistakes of the 1970s, when inflation was let loose at huge cost to growth. His words were aimed at rich-country central banks, but policymakers in emerging economies are the ones who should most take heed. In countries such as China, India, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia even the often dodgy official statistics show prices have risen by 8-10% over the past year; in Russia the rate is over 14%; in Argentina the true figure is 23% and in Venezuela it is 29%. If you measure the numbers correctly, two-thirds of the world's population will probably suffer double-digit rates of inflation this summer (see article).

アメリカは不況間近で、他の先進諸国の経済成長が鈍化していても、インフレは上昇を続けている。

ジャン・クロード・トリシェECB総裁は今週、1970年代の過ちについて警告した。

あの時、成長に大変な犠牲を強いてインフレは野放しにされた。

彼の言葉は富裕国の中央銀行を狙い撃ちしたものだったが、一番注意しなければいけないのは新興経済の政策立案者だ。

中国、インド、インドネシア、そしてサウジアラビアといった国では、怪しげなことも多い公式データが、一年間で8-10%も物価が上昇した、と示している。

ロシアでは14%を超えた。

アルゼンチンの本当のインフレ率は23%で、ベネズエラは29%。

正確に測れば、今年の夏は世界の人口の2/3が、二桁台のインフレに苦しむことになるだろう。

A 1970s reunion you really don't want to attend

1970年代同窓会、って、出たくないよorz

Taken as a whole (and using official figures), the average world inflation rate has risen to 5.5%, its highest since 1999. The main cause has been the surge in the prices of food and oil, which briefly soared above $135 a barrel this week. But Mr Trichet's concern is that higher headline rates could push up inflation expectations, leading to bigger pay demands, and so trigger a wage-price spiral, as in the 1970s. Central bankers' mistake then was to hold monetary policy too loose, so that higher oil prices quickly fed into other prices. So it is worrying that global monetary policy is now at its loosest since the 1970s: the average world real interest rate is negative.

全体として(ついでに公式データを使って)考えてみれば、世界の平均的なインフレは+5.5%で、1999年以来最高だ。

主な原因は食品と石油の価格急騰だ。

石油は今週、短期間だが、バレル$135を超えるまでに跳ね上がった。

だがトリシェ氏が心配しているのは、物価上昇がインフレ期待を押し上げ、これが賃上げ要求につながって、更に賃金物価上昇スパイラルを動かすことになるんじゃないか、ということだ。

そう、1970年代のように。

当時の中央銀行マンの過ちは、金融政策を緩めたまま放っておいたことだった。

このおかげで石油価格高騰は、素早く他の物価に広がってしまった。

だから、世界の金融政策が、今は1970年代以来最もゆるゆるになっているのは、心配なのである。

平均的な世界の実質金利はネガティブだ。

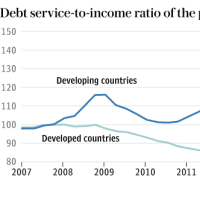

By slashing interest rates as inflation has climbed, has the Fed sowed the seeds of a new inflationary era? That case looks hard to prove in the rich world. Inflation rates of 3.9% in America and 3.3% in the euro area are far higher than central banks want, and inflation expectations are rising. If growth in the euro area remains robust, the ECB should certainly worry more about inflation. Yet so far there is little sign that higher food and oil prices are pushing up other prices in the rich economies. Wages have remained relatively subdued and core rates of inflation (excluding food and energy) are little higher than a year ago. Moreover, growth is expected to be below trend in America and Europe over the next year or so and unemployment is likely to climb, which will help to curb wage rises. America's consumer-confidence index has fallen to a 28-year low, which suggests that consumer spending will fall. This, in turn, will spur firms to cut costs and limit pay rises.

インフレが上昇する中で金利を引き下げることで、FRBは新たなインフレ時代の種を蒔いたのだろうか?

富裕世界では証明が難しそうだ。

アメリカの3.9%、ヨーロッパの3.3%というインフレ率は、中央銀行マンが目指すよりも遥かに高い。

それに、インフレ期待は上昇中だ。

ユーロ圏の経済成長が活発なら、ECBは勿論インフレの心配をもっとすべきだろう。

だがこれまでのところ、富裕国で、食品と石油の価格上昇が、他の物価を押し上げているという兆しは殆どない。

賃金は比較的抑え気味のままだし、コア物価上昇率(食品とエネルギーを除く)も一年前を僅かに上回るぐらいだ。

それにもまして、来年一年間かそこら、アメリカとヨーロッパの成長率はトレンド以下だと予測されているし、失業率は上昇しそうだ(これは賃金上昇を抑える助けになるだろう)。

アメリカの消費者景況感指数は28年ぶり最低に落ち込んだ。

つまり、消費者支出はヘルと言うことだ。

そしてこれは、企業にコスト削減と賃上げ制限をさせるだろう。

The picture is very different in emerging countries. Prices are rising much faster partly because food accounts for a bigger chunk of their consumer-price indices. But wages (rising at nearly 30% a year in Russia) and core-inflation rates are also accelerating. Many of these economies are operating close to full capacity, where inflation is more likely to take hold.

新興国での状況はかなり異なっている。

これらの国の消費者物価指数の中でしめる食品の割合が大きいということもあり、価格は遥かに速いペースで上昇中だ。

だが給与(ロシアでは年間30%近く上がっている)とコア・インフレ率も、加速中だ。

これらの新興経済の多くは、キャパ限界近くで活動しており、インフレが発生する可能性はもっと高い。

There are alarming similarities between emerging economies today and the rich world in the 1970s when the Great Inflation lifted off. Many policymakers in emerging markets view the rise in inflation as a short-term supply shock and so see little need to raise interest rates. Instead they are using price controls and subsidies to cap prices. Money supplies are growing almost three times as fast as in the developed world. Many central banks are still not fully independent. And inflationary expectations are not properly anchored, increasing the risk of a wage-price spiral. Emerging markets may as well be inviting the muggers into their own homes.

今日の新興経済と、大インフレ時代が始まった1970年代の富裕国の間には、警戒すべき類似点がある。

新興市場の多くの政策立案者は、インフレ上昇を短期的なサプライ・ショックと考えている。

だから金利を引き上げる必要はほとんどない、と。

その代わりに彼らは、価格統制と価格に上限を定めるための補助金を利用している。

マネー・サプライは、先進国ではほぼ3倍の速さで上昇中だ。

多くの中央銀行は未だに完全に独立していない。

また、インフレ期待は適切に固定されておらず、賃金物価上昇スパイラルのリスクを高めている。

新興市場も、自宅にチンピラ強盗を招き入れているかもしれない。

Watch your back

背中に気をつけろ

Rising inflation, like so much of the world economy in recent years, can be explained partly by the increasingly complex links between developed and emerging economies. Emerging economies shared some responsibility for America's housing and credit bubble. As Asian economies and Middle East oil exporters ran large current-account surpluses, they piled up foreign reserves (mostly in American Treasury securities) in order to prevent their currencies from rising. This pushed down bond yields. At the same time, cheap imports from China and elsewhere helped central banks in rich economies hold down inflation while keeping short-term interest rates lower than in the past. Cheap money fuelled America's bubble.

近年の世界経済の殆どと同じく上昇するインフレは、先進国と新興国の益々複雑化する関係で、部分的に説明可能。

新興経済は、アメリカの住宅・信用バブルの責任の一端を担っている。

アジア経済と中東産油国が莫大な経常黒字を叩き出す中、自分達の通貨が値上りしないように、これらの国は外貨を積み上げた(殆どはアメリカ国債で)。

これが国債利回りを押し下げた。

同時に、中国その他の安物輸入品が、富裕国の中央銀行がインフレを抑制しながら、短期金利をこれまでよりも低くしておくのを助けしていた。

Now that this bubble has burst, the cross-border monetary stimulus has changed direction. As the Fed has cut interest rates, emerging economies that link their currencies to the dollar have been forced to run a looser monetary policy, even though their economies are overheating. Emerging economies with currencies most closely aligned to the dollar, notably in Asia and the Gulf, have seen the biggest price rises. Countries, such as Mexico, that have more flexible exchange rates and are more committed to inflation targets have done better.

今、そのバブルが弾け、国境を越えた金融の刺激策は矛先を変えた。

FRBが金利を引き下げたので、自国通貨をドルに連動させていた新興経済は、自国経済が過熱しているにも拘らず、金融政策を緩和しなければならなくなった。

ドルに一番引っ付いていた通貨の新興経済(特にアジアと湾岸)は、物凄い物価上昇を目撃している。

もっとフレキシブルな変動為替相場を採用していり、インフレ目標を厳しくしていたメキシコのような国は、そこまでヒドイ目に遭っていない。

Even if the Fed's interest rate suits the American economy, global interest rates are too low. In turn, the unwarranted stimulus to demand in emerging economies is further pushing up commodity prices; so too is speculative buying by investors seeking higher returns than from bond yields, which are still being depressed by the emerging economies' build-up of reserves. This stokes inflationary pressures in America and Europe and makes life difficult for rich-country central banks.

FRBの利上げは、アメリカ経済にあっていたとして、世界の金利は低過ぎる。

そして、新興経済での根拠のない需要刺激は、物価を更に押し上げている。

新興経済の外貨貯め込みのおかげで、未だに落ち込んでいる国債よりも高いリターンを求める投資家による、投機買いも同様だ。

これはアメリカとヨーロッパではインフレ圧力を生み、富裕国の中央銀行の舵取りを困難にしている。

Loose money in America and rigid exchange rates in emerging economies are a perilous mix. The longer emerging economies hold down their exchange rates, the greater the risk of rising global inflation. Admittedly, exchange-rate appreciation is not as simple a remedy for emerging economies as some claim: a rise in interest rates and the expectation of a further appreciation in the exchange rate could, perversely, exacerbate inflation by sucking in more capital; and setting the exchange rate free risks massive overvaluation. But with an economic serial killer on the loose, one way or another monetary policy will have to tighten and exchange rates rise.

アメリカの緩い金融と、新興経済の厳格な為替レートは、危険な組み合わせだ。

新興経済が為替レートを長く抑え付ければ抑え付けるほど、世界的インフレが上昇するリスクは大きくなる。

勿論、一部の連中が言ってるほど、為替レート上昇ってのは新興国にとって簡単な治療法じゃない。

金利引き上げや為替レート上昇期待は、おかしなことに、もっと沢山資本を飲み込んで、インフレを悪化させるかもしれない。

それに、為替レートを野放しにすることは、物凄い過大評価のリスクがある。

とはいえ、経済連続殺人犯が野放しになっている中では、何らかの金融政策は引き締めなければならないし、為替レートも上昇しなければならない。