Cherry and Silk

(chehogh94.jpg+silkanim.gif)

Kato, do you like cherry and silk, don't you?

Yes, I do. How about you, Diane?

I like both. Actually, I love a cheesecake with cherry topping.

(cheesecake9.jpg)

Oh, do you? ... me, too.

And I like to wear my favorite silk dress.

Yes, yes, yes..., I know, I know.

Then how come you've brought up cherry and silk today?

Look at the following picture again.

(chehogh94.jpg)

Take a close look at the above picture! Now, what comes up in your mind?

Well ... a geisha girl standing by the cherry trees, isn't she?

Is that all you've come up with?

Tell me, Kato, what else you expect me to come up with?

"The Cherry Orchard"

The cherry orchard...? Where is it? In Stanley Park? Which orchard are you talking about?

I'm talking about a play called "The Cherry Orchard," which was written in 1903 by Russian playwright Anton Chekhov.

(chehov02.jpg)

Diane, have you ever seen the above play?

No, I don't think so.

Well ... I've pasted the video clip here for you. Why don't you take a look at Part 1 of the play.

Kato, this play is too old. It was written in 1903, wasn't it?

Yes, it was, but it is still quite famous. Besides, this play gave a big influence to Eugene O'Neill, George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Miller.

Oh, did it? I didn't know that. In any case, people nowadays don't talk much about the above play any more, do they?

I guess not.

Then how come you've brought up the above play?

Well ... the title of the play reminds me of the following picture.

(chehogh94.jpg)

Are you saying that a geisha girl shows up in the above play?

No, I'm not. As far as I know, a Japanese geisha doesn't show up in the play.

But the above picture shows a Japanese geisha girl, doesn't it?

Yes, it does. Actually, Anton Chekhov was once impressed profoundly by a certain Japanese girl.

Are you sure, Kato? I've never heard that Anton Chekhov went to Japan.

No, he never went to Japan.

Then what makes you think that Chekhov was once impressed by a certain Japanese girl?

Anton Chekhov recalled a certain Japanese woman at his death bed.

How do you know?

... 'Cause I was at his death bed in my dream.

Don't be foolish, Kato! I'm quite serious. By the way, what brought up Anton Chekhov in the first place?

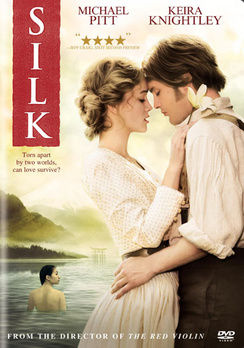

Good question! The other day, I borrowed the following DVD from Vancouver Public Library.

(lib30509q.gif)

■"Actual Catalogue Page"

So, you viewed the above DVD on May 8, 2013---ten years ago, and then jotted down the long comment, didn't you?

Yes, I did. It is an amazing and fascinating movie.

(silk01.jpg)

This is a 2007 film directed by François Girard, a French-Canadian director, based on the novel written by Alessandro Baricco, an Italian author.

It is a story of a French silkworm merchant-turned-smuggler named Hervé Joncour in 19th century France who travels to Japan for his town's supply of silkworms after a disease wipes out their African supply.

Before the journey, he gets married to Hélène, a teacher and keen gardener.

He loves her so much.

During his stay in Japan, however, he becomes obsessed with the concubine (played by Sei Ashina: 芦名 星) of a local baron.

On his first visit to the secluded village in the Northern part of Japanese mainland, she handed him a note, which reads in Japanese: "Come back or I shall die."

She appears mysteriously attractive. Hervé Joncour never knows her name.

The concubine seems attracted to this silkworm smuggler, yet she introduces a girl to him one night, instead of sleeping with him herself.

His obsession somewhat puzzles me because he has never communicated with the concubine verbally---let alone sexually.

In any case, his obsession is so strong that he seems to do anything to meet her again, but to no avail.

Then he receives a long letter from the mysterious concubine, written in Japanese.

He takes the letter to Madame Blanche for translation, who agrees, providing he never comes to see her again.

Madame Blanche is a Japanese woman whose French merchant-husband has been long dead.

As a owner-and-manager of a high-class brothel, she lives in Lyon, a city in east-central France, and she is known for giving the small blue flowers that she wears to her clients.

The letter is a deeply moving declaration of love.

After his three journeys to Japan, his wife becomes ill and eventually dies.

Hervé finds a tribute of small, blue flowers on her grave.

He seeks out Madame Blanche once more, believing her to have written the letter, but Madame Blanche has moved to Paris without giving him a new address.

Hervé Joncour almost knocks at every door in Paris to find Madame Blanche, and finally he meets her.

Madame Blanche reveals a profound secret to him.

This is a big twist in this film.

I'd better not tell you about it.

After this revelation, Madame Blanche tells him that, more than anything, his wife loved him.

Too late, Hervé finally realizes that it was Hélène who was his true love after all.

It is a poetic film and really moving.

The Japanese scenery is authentic because it was filmed in a secluded part outside the city center of Sakata (酒田市、山形県).

You might be convinced that obsession is not love, but that it's more like illusion. Love is real and it's more like devotion.

I see... So you jotted down a rather philosophical comment at the very end, didn't you?

Yes, I did.

But I don't see any connection between the above movie and Anton Chekhov. Does Chekhov have anything to do with the above movie?

Yes, of course, he does. Otherwise, I wouldn't have talked about him in the first place.

Tell me, then, what on earth makes you think that the above movie has something to do with Anton Chekhov.

Obsession! ... That's it... Hervé Joncour was obsessed with the mysterious concubine. Likewise, Anton Chekhov became obsessed with a certain Japanese woman.

Who the heck is that certain Japanese woman?

Read the following excerpt.

Chekhov died on July 15, 1904 after the Russo-Japanese War began in February.

Three days before his death, he wrote a letter to his friend: "Japan will probably lose the war, and I'm sad thinking about Japan's defeat."

When he reached the end of his life, Chekhov muttered "A Japanese woman ..."

But nobody understood his following words.

Mrs. Chekhov let him sip a bit of champagne.

He said to his doctor, "I'm gonna die" in German.

Then he looked up at his wife and said with a faint smile, "I haven't tasted champagne for a long time, haven't I?"

He slowly took the last breath and died quietly.

It was 3 o'clock in the morning.

Chekhov had never come to Japan, yet he muttered about a Japanese woman.

Why?

I was profoundly puzzled.

Later when I happened to read a book titled "Chekhov and Japan" written by Nobuyuki Nakamoto, I felt that I'd solved the mystery.

In the spring of 1890, Chekhov traveled to Sakhalin, and on his way back he dropped in at Blagoveshchensk---a town along the Amur River near the Chinese border.

(blagioveshchensk.png)

(chehogh90.jpg)

Something happened on June 26, 1980.

The next day, Chekhov wrote a letter to his writer-friend.

(maiko19.png)

Japanese women seem to understand shame in a peculiar way.

When I went to bed with this Japanese woman, she didn't put out the light.

When I asked a series of salacious questions, she answered rather frankly---unlike Russian women who are pretentious with airs and graces.

She smiled constantly without much talking.

When it came to the love-making, she showed such exquisite manners and techniques that you would feel as if you were riding an expertly-trained horse rather than going to bed with a hooker.

Once it was over, she grasped my little dick lovingly and wiped it with soft tissues taken out from the sleeve of her kimono.

It was a grateful surprise, indeed.

Oh, I'm in love with Amur.

I wish I could live here for another two years.

... beautiful, spacious, and free and warm.

In France and Switzerland, I've never even once tasted the freedom like this.

At that time, in Siberia Primorye, there were a number of "Karayuki-san" or "Japanese hookers in foreign-land."

Chekhov certainly met one of those Japanese women.

(chehogh94.jpg)

This woman inspired an image of warmth and tenderness in Chekhov, and later led to a creation of the play: "The Cherry Orchard."

It was this modest yet unforgettable Japanese woman who taught Chekhov the beauty of pure white cherry.

(translated by Kato; pictures from Denman Library)

SOURCE:

pp.237-239 "Take a Walk in History"

Published in April 15, 2010

Author: Kazutoshi Handou

『ぶらり日本史散策』 著者: 半藤一利

2010年4月15日 第1版発行

発行所: 株式会社 文藝春秋

So, Kato, you're saying that Chekhov was obsessed with this Japanese woman, aren't you?

Yes, I am.

Quite interesting, isn't it? Hervé Joncour didn't have sex with the concubine, yet he was quite obsessed with the mysterious woman. On the contrary, Chekhov seems to have attracted to the exquisite manners and techniques of the Karayuki-san.

Yes, you're right on, Diane. Hervé Joncour looks like a man who tends to look at the spiritual side while Chekhov seems like a man who focuses on the technical side.

Tell me, Kato, which woman you prefer to become obsessed with---the concubine or the hooker in foreign land?

It's hard to tell, but I'd say both.

【Himiko's Monologue】

"Karayuki-san (唐行きさん)" were Japanese women who traveled to East Asia and Southeast Asia in the second half of the 19th century to work as prostitutes.

It literally means "Ms. Gone-to-China."

(karayuki2.gif)

Karayuki-san in Siberia

Many of these women were said to have originated from the Amakusa Islands of Kumamoto Prefecture, which had a large and long-stigmatized Japanese Christian community.

Many of the women who went overseas to work as karayuki-san were the daughters of poor farming or fishing families.

The mediators who arranged for the women to go overseas would search for those of appropriate age in poor farming communities and pay their parents, telling them they were going overseas on public duty.

The mediators would then make money by passing the girls onto people in the prostitution industry.

With the money the mediators received, some would go on to set up their own overseas brothels.

In any case, I hope Kato will write another interesting article soon.

So please come back to see me.

Have a nice day!

Bye bye ...

If you've got some time,

Please read one of the following articles:

(sylvie121.jpg)

■"Amazing Two-legged Pooch"

■"Asexual Thought"

■"At a Crossroads"

■"Banana @ Eden"

■"Biker Babe & Granny"

(biker302.jpg)

■"Bird In A Cage"

■"Botchan & Glenn Gould"

■"Bye Bye Trump"

■"Covent Garden"

■"Diane Chatterley"

■"Eight the Dog"

(vanc700.jpg)

■"From Canada to Japan"

■"From Gyoda to Vancouver"

■"From Summer to Eternity"

■"Fjiyama Geisha"

■"Glorious Summer"

■"Halifax to Vancouver"

(dogs17.gif)

■"God Is Coming!"

■"Golden Shower"

■"Hitler and Trump"

■"Hot October"

■"Killer Floods"

■"Mistery of Dimension"

Hi, I'm June Adams.

"The Cherry Orchard" concerns an aristocratic Russian woman and her family as they return to the family's estate, which includes a large and well-known cherry orchard, just before it is auctioned to pay the mortgage.

While presented with options to save the estate, the family essentially does nothing and the play ends with the estate being sold to the son of a former serf, and the family leaving to the sound of the cherry orchard being cut down.

Introduction to

"The Cherry Orchard"

The story presents themes of cultural futility---both the futility of the aristocracy to maintain its status and the futility of the bourgeoisie to find meaning in its newfound materialism.

In reflecting the socio-economic forces at work in Russia at the turn of the 20th century, including the rise of the middle class after the abolition of serfdom in the mid-19th century and the sinking of the aristocracy, the play reflects forces at work around the globe in that period.