A Professor of International Relations at Gunma Prefectural Women’s University

NOGUCHI, Kazuhiko

In recent strategic studies, China is now the main actor. Rising China has grown into a superpower that threatens the position of the United States. After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States became the sole superpower in the international system. For the first time since the birth of modern nation-states, a unipolar system emerged. However, the unipolar system did not last long. As China became more powerful as an emerging superpower, the world is shifting back to a bipolar system, just as it did during the Cold War. How should the United States and Japan deal with China in this period of international structural change?

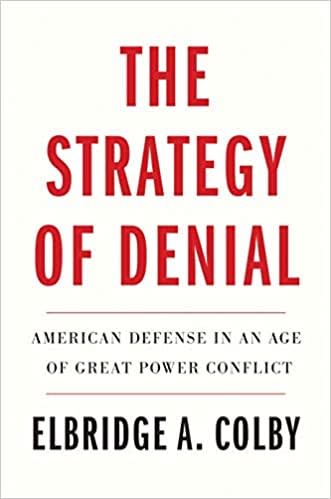

In addressing these problems of grand strategies, a number of important research books have been published to serve as references. The main books among them are The Strategy of Denial (Yale University Press, 2021) by Mr. Elbridge Colby, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Trump administration; Getting China Wrong (Polity, 2022) by Dr. Aaron Friedberg (Princeton University); Danger Zone (W. W. Norton, 2022) by Dr. Hal Brands (Johns Hopkins University) and Dr. Michael Beckley (Tufts University). The last book will be published next month in a Japanese translation by strategist/geopolitical researcher Dr. Masashi Okuyama.

A "Denial Strategy" to Prevent China's Regional Hegemony

Colby's "denial Strategy" advocates forming an anti-China coalition to prevent China from establishing regional hegemony in Asia. The United States plays the main role in this balancing coalition because China's expansion in the Western Pacific would surely threaten the vital national interests of the United States, thus it has a good strategic reason to counter China. This is almost the same as the containment policy recommendations for China advocated by realists such as Dr. John Mearsheimer (University of Chicago) and Dr. Stephen Walt (Harvard University).

Mearsheimer points out the usefulness of a strategy to contain China as follows.

"The optimal strategy for dealing with a rising China is containment. It calls for the United States to concentrate on keeping Beijing from using its military forces to conquer territory and more generally expand its influence in Asia. Toward that end, American policymakers would seek to form a balancing coalitions with as many of China's neighbors as possible...Containment is essentially a defensive strategy, since it does not call for starting wars against China. In fact, containment is an alternative to war with a rising China" (Tragedy of Great Power Politics, W. W. Norton, 2014, pp. 384-385).

Walt also argues that.

"The United States would maintain a significant military presence in Asia (primary air and naval forces) and continue to build cooperative security partnerships with its current Asian allies...maintaining the U.S. military presence in Asia also lays the foundation for a future effort to contain China, in the event that China's rising power eventually leads to a more ambitious attempt to establish a hegemonic positions in East Asia...the United States has no need to occupy or dominate these regions; it just needs to ensure that no other state (China) is able to do so (in Asia)" (Taming American Power, W. W. Norton, 2005, pp. 241-242).

Thus, containment is a strategy to deny the opportunity for China to establish regional hegemony. Please note that containment is a defensive strategy. It prevents China from making its territorial conquests in Asia a fait accompli; it does not intervene in China's domestic politics to overthrow the Communist regime or to democratize the country. In Colby's view, if China annexes Taiwan, it could then easily bring the Philippines under its control and isolate Japan. If this were to happen, China would expand its power in the Western Pacific and threaten the security of the U.S., so the invasion of Taiwan should be prevented as a springboard for such an expansion. To this end, Colby argues that the best strategy is for the U.S., Japan, Australia, and other Asian countries to cooperate in reminding China that an invasion of Taiwan would be too costly and to use a strategy of denial deterrence to prevent a war from starting.

Failure of Engagement Strategies with China

Friedberg's book, Getting China Wrong, argues how successive U.S. administrations in the post-Cold War era have been wrong in their engagement policies in the hope that China would democratize. He concludes, like the realists, that by favoring China, the U.S. has turned it into a huge rival country that threatens its own national interests, contrary to its expectations.

In his words, "Instead of a liberal and cooperative partner, China has become an increasingly wealthy and powerful competitor, repressive at home and aggressive abroad... successive US administrations sought to promote 'engagement' : ever-deepening commercial, diplomatic, scientific, educational, and cultural ties between China and West … By welcoming Beijing into the US-dominated, post-Cold War international system, American policy-makers hoped to persuade China's leaders that their interests lay in preserving the existing order... Finally, far from becoming a satisfied supporter of the international status quo, Beijing is now pursuing openly revisionist aims...engagement failed because its architects and advocates got China wrong" (Getting China Wrong, pp. 1-3).

The criticism by Mearsheimer is also harsh, as follows. Namely, "Engagement may have been the worst strategic blunder any country has made in recent history: there is no comparable example of a great power actively fostering the rise of a peer competitor. And it is now too late to do much about it."

In short, the U.S. engagement policy toward China has been a disaster that has helped China grow into a powerful revisionist power. To correct this mistake and get China right in the future, he argues, we must adopt a policy of containing a rising China, pulling Russia away from China, and imposing costs on its aggressive behavior. "The old Washington consensus in favor of engagement has finally broken down, giving rise to 'growing calls ...to contain China'...The immediate task confronting US and allied strategists is therefore to sore up the regional military balance, bolstering deterrence and reducing the likelihood that, even in a crisis, China's leaders could reasonably conclude that they stood to gain by using of force" (Getting China Wrong, pp. 147, 187).

Perhaps the significant difference between Colby's and Friedberg's analyses is that the former looks exclusively to China's moves toward regional hegemony as the source of the U.S.-China conflict, while the latter adds "the CCP's Leninist"(Getting China Wrong, pp. 174) to its ambition.

The "Danger Zone" Strategy.

Brands and Beckley, The Danger Zone, presents a somewhat different view of China than the two books mentioned above. That is, China's power is at its peak now and will decline in the future due to demographic changes and other factors. Since a declining superpower increases the motivation for "preventive war," the coming decade or so has been "dangerous," and the U.S. and its allies should prevent China from starting a war against Taiwan with a skillful "danger zone" strategy. To that end, they argue, democracies such as the United States and Japan should unite to prevent China from invading Taiwan.

The Taiwan contingency is also a major issue for Japan's security. The most serious challenge Japan faces is that China would use nuclear blackmail to prevent Japan from intervening in a Taiwan contingency. To this conundrum, Brands and Beckley boldly state a clear countermeasure. As discussed below, the U.S. would have options of attacking China's military assets with nuclear weapons to deter China from using nuclear weapons or threats in a punitive manner.

They also hope that if the unity of the world's democratic powers continues over the long term, China will eventually crumble and succumb. At the same time, in the medium or short term, they recommend a double containment of China in Asia and Russia in Europe. These conclusions are a hybrid of Brands' research analyzing the success of the containment strategy against the Soviet Union and Beckley's unique examination of the peculiarities of American power. In What Good Is Grand Strategy (Cornell University Press, 2014), Brands spoke highly of the containment strategy initiated by the Truman administration and the Reagan administration's strategy against the Soviet Union. In Unrivaled (Cornell University Press, 2018), Beckley analyzed that American power has unique advantages over other countries and will continue to do so.

As these research books suggest, it is certain that the U.S. is shifting to a strategy of containment against China, and preventing a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is surely the biggest strategic challenge in the near future. In any dispute over Taiwan, China will try to create a fait accompli within days or weeks. Therefore, the U.S. needs to dramatically strengthen deterrence and undermine Beijing's confidence in its ability to successfully conquer Taiwan. As Michelle Flournoy (Center for a New American Security) and Michael Brown (Stanford University) point out, "Time is running out for defending Taiwan."

The Cost of a Denial Strategy

As for the best strategy against China, Colby's proposal for a "denial strategy" seemed to me to be the most realistic. The gist of his proposed strategy is as follows.

"The United States cannot handle all of the world’s potential conflicts on its own, and certainly not simultaneously. It should concentrate on Asia and enable Europe to bolster its own defenses against the threat from Russia. And it is Germany that has to play the central role."

The problem with a denial deterrence strategy is that it is costly. First, to prevent China from launching an invasion abroad, allies such as the U.S. and Japan would have to deploy a conventional force large enough to clearly convince China that the cost of winning the war would be too great to justify it. Colby argues that this requires Japan to spend 3% of its GDP on defense to strengthen its military power. Japan is seriously short of forces. A senior Self-Defense Forces officer has stated, "If there is an emergency in the Nansei Islands, we would not last more than a few days [with our current forces]."

Second, it is unwise to bring democratic ideology into a containment strategy against China because it will alienate important nations such as Saudi Arabia, a major power in the Middle East, and Singapore, which faces the Strait of Malacca, a choke point in the region. Brands points out that "a war in which the U.S. leads a large coalition of democracies is probably one that China cannot win," but in order to counter China, we should gather many allies, not just democracies.

Third, since the unipolar era is over, the scarce strategic resources of the U.S. must be devoted to containment as a priority. In this regard, one researcher has critically stated, "the root cause of the so-called pivot to Asia’s failure is Washington’s continued belief that American power and interests are global and universal. If U.S. decisionmakers truly seek to reorient American strategic priorities, they need a clear hierarchy of the nation’s interests and obligations."

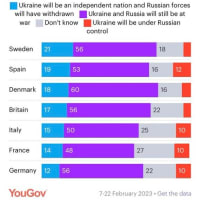

The dual containment of Russia and China overestimates American power. The U.S. does not have the capacity for a two-front military operation to fight Russia and China simultaneously. The shortage of ammunition in the U.S. military confirms this. Mark Cancian (Center for Strategic and International Studies) warned, "The United States has given Ukraine dozens of different munitions and weapon systems. In most instances, the amounts given to Ukraine are relatively small compared to U.S. inventories and production capabilities. However, some U.S. inventories are reaching the minimum levels needed for war plans and training. The key judgment for both munitions and weapons is how much risk the United States is willing to accept." If this weakening of supply capabilities continues, U.S. military capabilities will be severely impaired, and as a result, the U.S. will have difficulty containing China, which is much more powerful than Russia. In fact, the threat from Russia can be adequately addressed by the European nations alone. Russia's military budget is just one-fifth of NATO's, excluding the US, and just 6% of NATO's total. The delusions of Russophobia and liberal hegemony must be abandoned.

The Problem of Extended Deterrence in the Containment Strategy Against China

The challenge that still weighs heavily in the construction of a grand strategy will be China's nuclear threats against Japan and Taiwan. There is no clear answer to the classic question of extended deterrence (the nuclear umbrella): "Will Washington protect Tokyo and Taipei at the risk of New York? Colby is rather optimistic about this issue. He believes that the competition for resolve between the U.S. and China over Taiwan is not necessarily in China's favor because "China is exceedingly unlikely to invite its own destruction, given that this would mean the loss of everything it values-and the United States can see that." (The Strategy of Denial, p. 93). However, because the stakes in Taiwan are asymmetric between China and the United States, the threat against China tends to be "cheap talk." For China, control of Taiwan concerns its "core interests." For the United States, on the other hand, Taiwan is a question of belonging to a political entity thousands of kilometers away from the U.S. mainland. The balance of interests over Taiwan is favorable to China and unfavorable to the US. This imbalance of interests could undermine the U.S. threat of deterring China in its defense of Taiwan.

Brands and Beckley argue that the U.S. should go one step further and pursue a low-yield nuclear counterforce strategy against China.

"Although the United States would obviously prefer to keep a war over Taiwan non-nuclear, it needs to have the limited nuclear options-the ability to use low-yield weapons against ports, airfields, fleets, and other military targets-that would allow it to credibly respond credibly to, and thereby deter, Chinese nuclear threats" (Danger Zone, p. 185).

The question is whether the U.S. will really have such a commitment to the deterrence of punishment. Mr. Doug Bandow (The Cato Institute) doubts this. He says, "Taiwan, to be sure, is a valued friend. But is it worth nuclear war?... The American people have little reason to fight over the fate of the island. It is a humanitarian and human-rights issue, and a majority of Americans support providing aid if it is attacked by China. However, they do not want to go to war on behalf of Taiwan. They have no reason to risk Los Angeles for Taipei...The island is of no intrinsic value to America’s defense." The same logic may apply to the Japan-China dispute over the Senkaku Islands.

In a pioneering study in Japan on U.S.-China relations entitled The U.S.-China Strategic Relations (Chikura Shobo, 2018), there is concern about Japan becoming "peripheral" if the United States accepts Chinese regional hegemony, but the above intellectual's analysis should dispel that worry. Rather, the question is likely to be what is "military power that Japan can strategically utilize" (ibid., p. 326), as pointed out by Dr. Tetsuya Umemoto (University of Shizuoka), and how to pursue it. In this context, the question of whether or not Japan go nuclear seems unavoidable.

Whether the U.S. will protect Japan even at the risk of nuclear retaliation from China depends on its national interests. It is a question of the credibility of the nuclear umbrella. Therefore, if the U.S. and Japan share nuclear weapons, it is likely to be more effective in dissuading China from invading Japan. This is because in nuclear sharing, the Self-Defense Forces (SDF), not the U.S. troops, would be in charge of delivering nuclear bombs, thus lowering the hurdle for the use of nuclear weapons. Of course, there is strong opposition to this nuclear sharing, but the counterarguments are contradictory and illogic.

Dr. Yoko Iwama (National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies) argues, "even under the scheme of nuclear sharing...even if Japan wanted to use nuclear weapons to defend its national interest, it is inconceivable that the US would easily go along.” In short, the U.S. will not allow the use of nuclear weapons for Japan's national interest. On the other hand, she also says, "The relationship of trust which makes the US nuclear umbrella work when the need arises and enables the US to help Japan when Japan needs help is the essence of the deterrence provided under the Japan-US alliance." In other words, the U.S. would be willing to help Japan at its own expense in extended deterrence. In the case of nuclear sharing, the US is unwilling to pay the cost for Japan's national interests, while in the case of extended deterrence, the Americans are prepared to give enormous amounts of their lives for Japan's national interests. One wonders why the US is suddenly willing to make sacrifices when it comes to extended deterrence. Is such a thing really possible?

The national interests of Japan and the US are not identical. The U.S. will pay a significant cost if it tries to protect Japan. To resolve this strategic dilemma, the above-mentioned Walt suggests the suspension of extended deterrence and the nuclear armament of Japan. He says, "While a U.S. halt to nuclear assurances might encourage some states to go nuclear themselves, it does not mean that a Japanese or German nuclear capability would be an obviously terrible outcome from a purely American point of view." In the end, it seems that what the Chinese challenge and the Taiwan contingency pose to the Japanese people is our "responsibility" and "resolve" for constructing a new security strategy.

NOGUCHI, Kazuhiko

In recent strategic studies, China is now the main actor. Rising China has grown into a superpower that threatens the position of the United States. After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States became the sole superpower in the international system. For the first time since the birth of modern nation-states, a unipolar system emerged. However, the unipolar system did not last long. As China became more powerful as an emerging superpower, the world is shifting back to a bipolar system, just as it did during the Cold War. How should the United States and Japan deal with China in this period of international structural change?

In addressing these problems of grand strategies, a number of important research books have been published to serve as references. The main books among them are The Strategy of Denial (Yale University Press, 2021) by Mr. Elbridge Colby, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Trump administration; Getting China Wrong (Polity, 2022) by Dr. Aaron Friedberg (Princeton University); Danger Zone (W. W. Norton, 2022) by Dr. Hal Brands (Johns Hopkins University) and Dr. Michael Beckley (Tufts University). The last book will be published next month in a Japanese translation by strategist/geopolitical researcher Dr. Masashi Okuyama.

A "Denial Strategy" to Prevent China's Regional Hegemony

Colby's "denial Strategy" advocates forming an anti-China coalition to prevent China from establishing regional hegemony in Asia. The United States plays the main role in this balancing coalition because China's expansion in the Western Pacific would surely threaten the vital national interests of the United States, thus it has a good strategic reason to counter China. This is almost the same as the containment policy recommendations for China advocated by realists such as Dr. John Mearsheimer (University of Chicago) and Dr. Stephen Walt (Harvard University).

Mearsheimer points out the usefulness of a strategy to contain China as follows.

"The optimal strategy for dealing with a rising China is containment. It calls for the United States to concentrate on keeping Beijing from using its military forces to conquer territory and more generally expand its influence in Asia. Toward that end, American policymakers would seek to form a balancing coalitions with as many of China's neighbors as possible...Containment is essentially a defensive strategy, since it does not call for starting wars against China. In fact, containment is an alternative to war with a rising China" (Tragedy of Great Power Politics, W. W. Norton, 2014, pp. 384-385).

Walt also argues that.

"The United States would maintain a significant military presence in Asia (primary air and naval forces) and continue to build cooperative security partnerships with its current Asian allies...maintaining the U.S. military presence in Asia also lays the foundation for a future effort to contain China, in the event that China's rising power eventually leads to a more ambitious attempt to establish a hegemonic positions in East Asia...the United States has no need to occupy or dominate these regions; it just needs to ensure that no other state (China) is able to do so (in Asia)" (Taming American Power, W. W. Norton, 2005, pp. 241-242).

Thus, containment is a strategy to deny the opportunity for China to establish regional hegemony. Please note that containment is a defensive strategy. It prevents China from making its territorial conquests in Asia a fait accompli; it does not intervene in China's domestic politics to overthrow the Communist regime or to democratize the country. In Colby's view, if China annexes Taiwan, it could then easily bring the Philippines under its control and isolate Japan. If this were to happen, China would expand its power in the Western Pacific and threaten the security of the U.S., so the invasion of Taiwan should be prevented as a springboard for such an expansion. To this end, Colby argues that the best strategy is for the U.S., Japan, Australia, and other Asian countries to cooperate in reminding China that an invasion of Taiwan would be too costly and to use a strategy of denial deterrence to prevent a war from starting.

Failure of Engagement Strategies with China

Friedberg's book, Getting China Wrong, argues how successive U.S. administrations in the post-Cold War era have been wrong in their engagement policies in the hope that China would democratize. He concludes, like the realists, that by favoring China, the U.S. has turned it into a huge rival country that threatens its own national interests, contrary to its expectations.

In his words, "Instead of a liberal and cooperative partner, China has become an increasingly wealthy and powerful competitor, repressive at home and aggressive abroad... successive US administrations sought to promote 'engagement' : ever-deepening commercial, diplomatic, scientific, educational, and cultural ties between China and West … By welcoming Beijing into the US-dominated, post-Cold War international system, American policy-makers hoped to persuade China's leaders that their interests lay in preserving the existing order... Finally, far from becoming a satisfied supporter of the international status quo, Beijing is now pursuing openly revisionist aims...engagement failed because its architects and advocates got China wrong" (Getting China Wrong, pp. 1-3).

The criticism by Mearsheimer is also harsh, as follows. Namely, "Engagement may have been the worst strategic blunder any country has made in recent history: there is no comparable example of a great power actively fostering the rise of a peer competitor. And it is now too late to do much about it."

In short, the U.S. engagement policy toward China has been a disaster that has helped China grow into a powerful revisionist power. To correct this mistake and get China right in the future, he argues, we must adopt a policy of containing a rising China, pulling Russia away from China, and imposing costs on its aggressive behavior. "The old Washington consensus in favor of engagement has finally broken down, giving rise to 'growing calls ...to contain China'...The immediate task confronting US and allied strategists is therefore to sore up the regional military balance, bolstering deterrence and reducing the likelihood that, even in a crisis, China's leaders could reasonably conclude that they stood to gain by using of force" (Getting China Wrong, pp. 147, 187).

Perhaps the significant difference between Colby's and Friedberg's analyses is that the former looks exclusively to China's moves toward regional hegemony as the source of the U.S.-China conflict, while the latter adds "the CCP's Leninist"(Getting China Wrong, pp. 174) to its ambition.

The "Danger Zone" Strategy.

Brands and Beckley, The Danger Zone, presents a somewhat different view of China than the two books mentioned above. That is, China's power is at its peak now and will decline in the future due to demographic changes and other factors. Since a declining superpower increases the motivation for "preventive war," the coming decade or so has been "dangerous," and the U.S. and its allies should prevent China from starting a war against Taiwan with a skillful "danger zone" strategy. To that end, they argue, democracies such as the United States and Japan should unite to prevent China from invading Taiwan.

The Taiwan contingency is also a major issue for Japan's security. The most serious challenge Japan faces is that China would use nuclear blackmail to prevent Japan from intervening in a Taiwan contingency. To this conundrum, Brands and Beckley boldly state a clear countermeasure. As discussed below, the U.S. would have options of attacking China's military assets with nuclear weapons to deter China from using nuclear weapons or threats in a punitive manner.

They also hope that if the unity of the world's democratic powers continues over the long term, China will eventually crumble and succumb. At the same time, in the medium or short term, they recommend a double containment of China in Asia and Russia in Europe. These conclusions are a hybrid of Brands' research analyzing the success of the containment strategy against the Soviet Union and Beckley's unique examination of the peculiarities of American power. In What Good Is Grand Strategy (Cornell University Press, 2014), Brands spoke highly of the containment strategy initiated by the Truman administration and the Reagan administration's strategy against the Soviet Union. In Unrivaled (Cornell University Press, 2018), Beckley analyzed that American power has unique advantages over other countries and will continue to do so.

As these research books suggest, it is certain that the U.S. is shifting to a strategy of containment against China, and preventing a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is surely the biggest strategic challenge in the near future. In any dispute over Taiwan, China will try to create a fait accompli within days or weeks. Therefore, the U.S. needs to dramatically strengthen deterrence and undermine Beijing's confidence in its ability to successfully conquer Taiwan. As Michelle Flournoy (Center for a New American Security) and Michael Brown (Stanford University) point out, "Time is running out for defending Taiwan."

The Cost of a Denial Strategy

As for the best strategy against China, Colby's proposal for a "denial strategy" seemed to me to be the most realistic. The gist of his proposed strategy is as follows.

"The United States cannot handle all of the world’s potential conflicts on its own, and certainly not simultaneously. It should concentrate on Asia and enable Europe to bolster its own defenses against the threat from Russia. And it is Germany that has to play the central role."

The problem with a denial deterrence strategy is that it is costly. First, to prevent China from launching an invasion abroad, allies such as the U.S. and Japan would have to deploy a conventional force large enough to clearly convince China that the cost of winning the war would be too great to justify it. Colby argues that this requires Japan to spend 3% of its GDP on defense to strengthen its military power. Japan is seriously short of forces. A senior Self-Defense Forces officer has stated, "If there is an emergency in the Nansei Islands, we would not last more than a few days [with our current forces]."

Second, it is unwise to bring democratic ideology into a containment strategy against China because it will alienate important nations such as Saudi Arabia, a major power in the Middle East, and Singapore, which faces the Strait of Malacca, a choke point in the region. Brands points out that "a war in which the U.S. leads a large coalition of democracies is probably one that China cannot win," but in order to counter China, we should gather many allies, not just democracies.

Third, since the unipolar era is over, the scarce strategic resources of the U.S. must be devoted to containment as a priority. In this regard, one researcher has critically stated, "the root cause of the so-called pivot to Asia’s failure is Washington’s continued belief that American power and interests are global and universal. If U.S. decisionmakers truly seek to reorient American strategic priorities, they need a clear hierarchy of the nation’s interests and obligations."

The dual containment of Russia and China overestimates American power. The U.S. does not have the capacity for a two-front military operation to fight Russia and China simultaneously. The shortage of ammunition in the U.S. military confirms this. Mark Cancian (Center for Strategic and International Studies) warned, "The United States has given Ukraine dozens of different munitions and weapon systems. In most instances, the amounts given to Ukraine are relatively small compared to U.S. inventories and production capabilities. However, some U.S. inventories are reaching the minimum levels needed for war plans and training. The key judgment for both munitions and weapons is how much risk the United States is willing to accept." If this weakening of supply capabilities continues, U.S. military capabilities will be severely impaired, and as a result, the U.S. will have difficulty containing China, which is much more powerful than Russia. In fact, the threat from Russia can be adequately addressed by the European nations alone. Russia's military budget is just one-fifth of NATO's, excluding the US, and just 6% of NATO's total. The delusions of Russophobia and liberal hegemony must be abandoned.

The Problem of Extended Deterrence in the Containment Strategy Against China

The challenge that still weighs heavily in the construction of a grand strategy will be China's nuclear threats against Japan and Taiwan. There is no clear answer to the classic question of extended deterrence (the nuclear umbrella): "Will Washington protect Tokyo and Taipei at the risk of New York? Colby is rather optimistic about this issue. He believes that the competition for resolve between the U.S. and China over Taiwan is not necessarily in China's favor because "China is exceedingly unlikely to invite its own destruction, given that this would mean the loss of everything it values-and the United States can see that." (The Strategy of Denial, p. 93). However, because the stakes in Taiwan are asymmetric between China and the United States, the threat against China tends to be "cheap talk." For China, control of Taiwan concerns its "core interests." For the United States, on the other hand, Taiwan is a question of belonging to a political entity thousands of kilometers away from the U.S. mainland. The balance of interests over Taiwan is favorable to China and unfavorable to the US. This imbalance of interests could undermine the U.S. threat of deterring China in its defense of Taiwan.

Brands and Beckley argue that the U.S. should go one step further and pursue a low-yield nuclear counterforce strategy against China.

"Although the United States would obviously prefer to keep a war over Taiwan non-nuclear, it needs to have the limited nuclear options-the ability to use low-yield weapons against ports, airfields, fleets, and other military targets-that would allow it to credibly respond credibly to, and thereby deter, Chinese nuclear threats" (Danger Zone, p. 185).

The question is whether the U.S. will really have such a commitment to the deterrence of punishment. Mr. Doug Bandow (The Cato Institute) doubts this. He says, "Taiwan, to be sure, is a valued friend. But is it worth nuclear war?... The American people have little reason to fight over the fate of the island. It is a humanitarian and human-rights issue, and a majority of Americans support providing aid if it is attacked by China. However, they do not want to go to war on behalf of Taiwan. They have no reason to risk Los Angeles for Taipei...The island is of no intrinsic value to America’s defense." The same logic may apply to the Japan-China dispute over the Senkaku Islands.

In a pioneering study in Japan on U.S.-China relations entitled The U.S.-China Strategic Relations (Chikura Shobo, 2018), there is concern about Japan becoming "peripheral" if the United States accepts Chinese regional hegemony, but the above intellectual's analysis should dispel that worry. Rather, the question is likely to be what is "military power that Japan can strategically utilize" (ibid., p. 326), as pointed out by Dr. Tetsuya Umemoto (University of Shizuoka), and how to pursue it. In this context, the question of whether or not Japan go nuclear seems unavoidable.

Whether the U.S. will protect Japan even at the risk of nuclear retaliation from China depends on its national interests. It is a question of the credibility of the nuclear umbrella. Therefore, if the U.S. and Japan share nuclear weapons, it is likely to be more effective in dissuading China from invading Japan. This is because in nuclear sharing, the Self-Defense Forces (SDF), not the U.S. troops, would be in charge of delivering nuclear bombs, thus lowering the hurdle for the use of nuclear weapons. Of course, there is strong opposition to this nuclear sharing, but the counterarguments are contradictory and illogic.

Dr. Yoko Iwama (National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies) argues, "even under the scheme of nuclear sharing...even if Japan wanted to use nuclear weapons to defend its national interest, it is inconceivable that the US would easily go along.” In short, the U.S. will not allow the use of nuclear weapons for Japan's national interest. On the other hand, she also says, "The relationship of trust which makes the US nuclear umbrella work when the need arises and enables the US to help Japan when Japan needs help is the essence of the deterrence provided under the Japan-US alliance." In other words, the U.S. would be willing to help Japan at its own expense in extended deterrence. In the case of nuclear sharing, the US is unwilling to pay the cost for Japan's national interests, while in the case of extended deterrence, the Americans are prepared to give enormous amounts of their lives for Japan's national interests. One wonders why the US is suddenly willing to make sacrifices when it comes to extended deterrence. Is such a thing really possible?

The national interests of Japan and the US are not identical. The U.S. will pay a significant cost if it tries to protect Japan. To resolve this strategic dilemma, the above-mentioned Walt suggests the suspension of extended deterrence and the nuclear armament of Japan. He says, "While a U.S. halt to nuclear assurances might encourage some states to go nuclear themselves, it does not mean that a Japanese or German nuclear capability would be an obviously terrible outcome from a purely American point of view." In the end, it seems that what the Chinese challenge and the Taiwan contingency pose to the Japanese people is our "responsibility" and "resolve" for constructing a new security strategy.