●

http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20110522x3.html

ジャパンタイムズ

Debate awaits on child custody pact

By MAYA KANEKO

Kyodo

After years of foreign pressure, Japan finally decided Friday to sign a treaty to settle cross-border child custody disputes, but a heated debate is expected to continue as proponents of the pact hope the move leads to the formation of a system that will guarantee children's access to both parents after a divorce.

Japan has long been labeled a "haven for parental abductions" and a "black hole" for children removed internationally, by foreign parents unable to see their children because they have been taken to Japan by their former Japanese spouses.

In Japan, the tendency is for the courts to award mothers sole custody of any children after divorce.

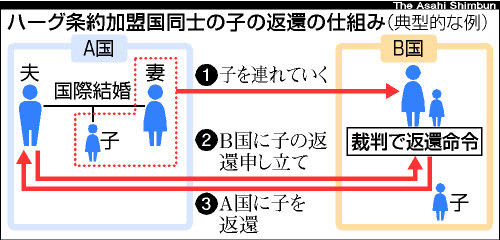

Among the Group of Seven countries, only Japan has not signed the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, which sets out the rules and procedures for promptly returning children under 16 to the country of their habitual residence in cases of international divorce. The pact currently has 84 parties.

The outcry from foreign parents separated from their children by failed marriages with Japanese has prompted 32 nations to jointly press Tokyo to join the treaty.

The government is now planning to submit bills by the end of this year to craft the legislation needed to accede to the convention.

But the move won't solve all of Japan's problems. Joining the pact will only provide a solution to parents abroad. Cases of "parental abductions" that occur in Japan, meanwhile, whil be left untouched.

Also, the pact's reach is unlikely to be retroactive, meaning it will only deal with future cases, in principle.

Out of concern that accession to the pact could endanger Japanese parties who have fled abusive relationships, Tokyo is considering stipulating in the domestic law that children will not have to be returned when they and their parent have suffered abuse by the other parent.

Japan is also thinking about exempting cases in which the Japanese parent could face criminal prosecution in his or her country of habitual residence and in which the former spouse abroad is deemed to have difficulty taking care of children.

Critics of the pact are calling on the government to carefully address the issue of abuse during the legislative process. Kazuko Ito, a lawyer who has opposed the signing of the convention, said Japan should specify the conditions for exempting the return of children when it drafts the domestic law.

Parents whose former spouses have taken their children — both Japanese and non-Japanese — are also carefully watching the process to see if it will lead to a change in their situation.

Such parents and their supporters have been lobbying for Japan to accede to the pact in the hope that it will change the customary situation in Japan, where it is not unusual for children to stop seeing their fathers after their parents break up.

Thierry Consigny, an elected member of the Assembly for French Overseas Nationals for Japan and North Asia, who has been supporting around 40 French parents officially recognized by Paris as having been separated from their children in Japan, said he hopes Tokyo will not unilaterally adopt criteria for recognizing cases of abuse.

"The 84 parties to the Hague Convention have their own criteria in identifying abuses, but they share international standards and make decisions on a case-by-case basis," he said. "We want Japanese courts to heed French standards as well in recognizing abuse cases to make a balance."

Consigny also said he expects joining the Hague Convention, which calls for securing children's access to both parents, will eventually lead to more exchanges between children and their noncustodial parents in Japan, which in his opinion will promote burden-sharing between divorced parents.

"The current sole custody system in Japan puts too much burden on child-rearing parents," he said. "Many single mothers who have abducted their children cannot enjoy private life as they bear heavy responsibility as breadwinners and are afraid of the possibility that their kids could be taken by exes."

France has adopted a joint custody system partly to lessen the child-rearing burden on working mothers by actively involving fathers, he said. Many of the countries that have pressured Japan — the 27-member European Union, the United States, Australia, Canada, Colombia and New Zealand — have such systems.

Mitsuru Munakata, a separated Japanese father who has been lobbying for a joint custody system in Japan, urged the government to address the plight of parents and children who cannot see each other in Japan while it prepares to join the Hague Convention.

"Honoring the spirit of the convention, the government should address the problems of separated parents and children in Japan. Otherwise, there is no meaning in signing the treaty that only deals with cross-border disputes because domestic cases would be discriminated against," he said.

Munakata said without real changes in the domestic situation, Japan's move to sign the pact will only be viewed as a way of dodging international pressure over child custody rows. He said in Japan, parents who do not have custody of their children are only allowed to spend two hours per month with their children on average.

Steve Christie, an American founder of a parental abduction victims association, said that his son, now 16, was abducted by the boy's Japanese mother when he was 10 and that a Japanese family court suggested Christie see his son only three times a year during vacations for a total of 36 hours.

As of January this year, the United States recognized 100 active cases of parental abduction to Japan involving 140 children. In addition, Washington is aware of 31 cases in which both parents and children live in Japan but one parent has been denied access.

Another American parent who has been lobbying the governments of both Japan and the United States to address the matter, said on condition of anonymity that the official figures represent only the tip of the iceberg, calling for efficient enforcement mechanisms to ensure access between separated parents and children.

In 2009, 146,408 couples with children under 20 were divorced in Japan, including couples composed of Japanese and foreigners, according to the latest government statistics. The number of divorces among Japanese and their foreign spouses reached about 19,404 cases that year.

Of the 146,408 divorces, 13.2 percent were cases in which fathers took sole care of children, while 83.2 percent were cases in which mothers did so. Only 3.6 percent involved both parents in child rearing.

2011年5月23日 JapanTimes

●Further debate awaits Japan after signing of child custody pact

http://www.japantoday.com/category/commentary/view/further-debate-awaits-japan-after-signing-of-child-custody-pact

TOKYO —

After years of foreign pressure, Japan finally decided Friday to sign a treaty to settle cross-border child custody disputes, but heated debate is expected to continue as proponents of the pact are hoping that the move will lead to a system that guarantees children’s access to both parents after divorce.

The Asian country has long been labeled by foreign parents who are unable to see their children after they have been taken to Japan by their former Japanese spouses as a ‘‘haven for parental abductions’’ and a ‘‘black hole’’ for children removed internationally, due to its failure to join the pact and its tendency to award mothers sole custody after divorce.

Among the Group of Seven countries, only Japan has not signed the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, which sets rules and procedures for the prompt return of children aged under 16 to the country of their habitual residence in cases of international divorce. The pact currently has 84 parties.

An outcry among foreign parents separated from their children after failed marriages with Japanese has prompted 32 nations to jointly press Tokyo to join the treaty.

Following Friday’s decision, the Japanese government aims to submit bills to the Diet by the end of this year to craft domestic legislation necessary to accede to the convention.

But Tokyo’s move would not solve all the problems. The pact would only provide a remedy to parents abroad, with cases of ‘‘parental abductions’’ occurring within Japan left untouched. Also, it would not be retroactive and would deal with future cases in principle.

Out of concern that accession to the pact could endanger Japanese parents and their children who have fled abusive relationships, Tokyo is considering stipulating in the domestic law that children will not have to be returned when they and their parent have suffered abuse by the other parent.

Japan is also thinking about exempting cases in which the Japanese parent could face criminal prosecution in his or her country of habitual residence and in which the former spouse abroad is deemed to have difficulties in taking care of children.

Critics of the pact are calling on the government to carefully address the issue of abuse in the legislative process. Kazuko Ito, a lawyer who has opposed Tokyo’s signing of the convention, said Japan should specify conditions for exempting the return of children in the planned domestic law.

Parents whose former spouses have taken their children—both Japanese and non-Japanese—are also carefully watching Japan’s domestic procedures to see if it would lead to a change in their situation.

Such parents and their supporters have been lobbying for Japan to accede to the pact in the hope that it would change the customary situation in the country, where it is not unusual for children to stop seeing their fathers after their parents break up.

Thierry Consigny, an elected member of the Assembly for French Overseas Nationals for Japan and North Asia, who has been supporting around 40 French parents officially recognized by Paris as having been separated from their children in Japan, said he hopes Tokyo will not unilaterally adopt criteria for recognizing cases of abuse.

‘‘The 84 parties to the Hague Convention have their own criteria in identifying abuses, but they share international standards and make decisions on a case-by-case basis,’’ he said. ‘‘We want Japanese courts to heed French standards as well in recognizing abuse cases to make a balance.’‘

Consigny also said he expects joining the Hague Convention, which calls for securing children’s access to both parents, will eventually lead to more exchanges between children and their noncustodial parents in Japan, which in his opinion would promote burden-sharing between divorced parents.

‘‘The current sole custody system in Japan puts too much burden on child-rearing parents,’’ he said. ‘‘Many single mothers who have abducted their children cannot enjoy private life as they bear heavy responsibility as breadwinners and are afraid of the possibility that their kids could be taken by exes.’‘

France has adopted a joint custody system partly to lessen the child-rearing burden on working mothers by actively involving fathers, he said. Many of the countries that have pressured Japan—the 27-member European Union, the United States, Australia, Canada, Colombia and New Zealand—have such systems.

Mitsuru Munakata, a Japanese separated father who has been lobbying for a joint custody system in Japan, urged the Japanese government to address the plight of parents and children who cannot see each other in Japan at the same time as it prepares to join the Hague Convention.

‘‘Honoring the spirit of the convention, the government should address the problems of separated parents and children in Japan. Otherwise, there is no meaning in signing the treaty that only deals with cross-border disputes as domestic cases would be discriminated against,’’ he said.

Munakata said without real changes in the domestic situation, Japan’s move to sign the pact will only be viewed as a way of dodging international pressure over child custody rows. He said in Japan, parents who do not have custody of their children are only allowed to spend two hours per month with their children on average.

Steve Christie, an American founder of a parental abduction victims association, said that his son, now 16, was abducted by the boy’s Japanese mother when he was 10 and that a Japanese family court suggested Christie see his son only three times a year during vacations for a total of 36 hours.

As of January this year, the United States recognized 100 active cases of parental abduction to Japan involving 140 children. In addition, Washington is aware of 31 cases in which both parents and children live in Japan but one parent has been denied access.

Another American parent who has been lobbying the governments of both Japan and the United States to address the matter, said on condition of anonymity that the official figures represent only the tip of the iceberg, calling for efficient enforcement mechanisms to ensure access between separated parents and children.

In 2009, 146,408 couples with children under 20 were divorced in Japan, including couples composed of Japanese and foreigners, according to the latest government statistics. The number of divorces among Japanese and their foreign spouses reached about 19,404 cases that year.

Of the 146,408 divorces, 13.2% were cases in which fathers took sole care of children, while 83.2% were cases in which mothers did so. Only 3.6% involved both parents in child rearing.

2011年5月23日 JapanToday