ガーディアンの記事「原発サムライ」の続きです。いい加減な意訳を載せておきました。間違いがたくさんあるかも知れませんが、他意はありません。宜しければ間違い箇所を教えてください。全体的に言えば、「原発サムライ」という言葉がちょっと気になる点を除けば、読むべき内容の記事だと思います。

The truth about the Fukushima 'nuclear samurai'

Japan's 'nuclear samurai' are risking their lives to avert catastrophe, but many are manual labourers unequal to the task

福島の「原発サムライ」の真実ーー日本の「原発サムライ」は命をかけて大災害を防ごうとしているが、多くはそういった仕事にはふさわしくない肉体労働者である。

To a world that doesn't know him, Shingo Kanno is one of the "nuclear samurai" – a selfless hero trying to save his country from a holocaust; to his family, Kanno is a new father whose life is in peril just because he wanted to earn some money on the side doing menial labour at the Fukushima nuclear plant.

原発侍カンノ・シンゴの紹介。

カンノのことを知らない外部の人間から見たら、自らの命を危険にさらしながらも、ホロコーストから国を救おうとする勇敢な「原発サムライ」に見えるかも知れない。だが、彼の家族からしたら全然そういう者ではない。子どもが出来たので、お金がちょっと欲しかったという理由だけで、福島原発での奴隷的労働者に従事してしまった男にすぎなかったのだ。

A tobacco farmer, Kanno had no business being anywhere near a nuclear reactor – let alone in a situation as serious as the one that has unfolded after the 11 March earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

カンノはたばこ農民だった。原子炉なんかには無関係だったし、ましてや今日の原発事故には関係ない。

His great-uncle, Masao Kanno, said: "People are calling them nuclear samurai because people are sacrificing their lives to try to fix a leak. But people like Shingo are amateurs: they can't really help. It shouldn't be people like Shingo."

シンゴの大叔父のカンノ・マサオが言うには、「放射能漏れを防ごうと命をかけているので、世間は彼らを原発さむらいと呼ぶかもしれないが、本当は素人で本当に力になることは出来ないんだよ。シンゴみたいのがやるべきじゃないんだ」。

(←「原発サムライ」のような言葉はないはずだ。「原発ジプシー」という言葉はあるが)。

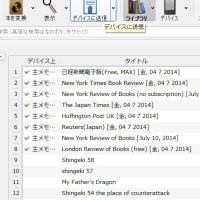

Masao Kanno is one of more than 500 people camped out on the hardwood floors of a sports centre in Yonezawa. The homes of most of them lie within 19 miles of the Fukushima plant. They worked at the plant, have family members who did, or passed it daily on the way to work or school.

カンノ・マサオは米沢(←福島県二本松市米沢のことだと思われる。場所的には原発とかなり近い)の体育館の床で仮住まいしている500人以上の避難者の一人だ。彼らの家の多くは福島原発30km以内にある。 (福島県二本松市米沢の地図)

(福島県二本松市米沢の地図)

彼らは原発で働いたり、家族の中に働く者がいたり、または通勤・通学の時に近くを通り過ぎる。

Before, they rarely thought about the down side to that proximity; now it rules their lives. Many of their homes are inside the evacuation zone, with radiation 17 times higher than background levels and tap water too contaminated to drink.

訳は省略

Those with a close personal connection to the crisis, like Masao Kanno, are moved and grateful for the personal courage of the 500 or so workers still at the plant. But where Japan's prime minister and others have conjured up cardboard heroes, he sees a flesh-and-blood relation.

カンノ・マサオのように原発に個人的に関わり合いのある者からすれば、500人もの労働者が今な原発で奮闘している姿は大いに感動的だ。しかし、総理たちヒーローをでっち上げようとしているにすぎない。

Shingo Kanno, who had been hired to do construction work, was released from his duties at Fukushima soon after the declaration of a nuclear emergency. As the crisis at the plant worsened, and the Japanese government widened the evacuation zone, he moved his wife and his infant daughter to his in-laws, where they would be safer.

カンノは原発事故後には原発から解放され、妻子たちを安全な場所に避難させた。

He also helped evacuate his extended family from their home town of Minamisoma, which is within the 30km exclusion zone, to the sports centre and other shelters. Then, his relatives say, Kanno got a call from the plant asking him to go back to work.

危険地域の南相馬からの避難がすんだと思ったら、原発側から仕事に戻ってくるように電話があったのだ。

His whole family took turns getting on the phone to tell him not to go. They reminded him that he was a farmer, not a nuclear engineer, that he did not have the skills for such a sophisticated crisis. They said he should think of his responsibilities to his parents and his baby daughter.

"I told him: 'You have a family now. You shouldn't be thinking about the company – you should be thinking about your own family,'" said Masao Kanno.

家族全員が「原発なんかに戻るんじゃない、お前はただの農民にすぎないじゃないか。自分の家族の責任を考えなさい」といった。

But on Friday Shingo Kanno went back anyway. The family have not heard from him since.

In the meantime, the cult of the nuclear samurai has only grown. Japanese television aired an interview with a plant worker on Monday offering a harrowing insider's account of the struggle for the reactors.

しかし、カンノシンゴは金曜日に戻ってしまい、それ以来消息を聞いていない。原発サムライ・カルト(←原発労働者を英雄視するメディア像のことか)が大きくなっただけだ。日本のテレビは、原発労働者のインタビューを放映した。

The worker, his face hidden from view, described sirens blaring, billowing smoke, explosions so powerful the earth rumbled, water sloshing in the pool of spent atomic fuel. Then he touched on his own complicated emotions before pulling out of the plant. "The people left behind – I feel really sorry for them," the worker said. "It was a hard decision to make, but I had a strong feeling that I wanted to get out."

労働者は匿名で、原発の中の凄まじい状況を語った。それから、彼が原発に残してきてしまった同僚に対する複雑な感情に触れた。「残してきた人には本当にすまないと思う。辛い決断だったけれども、どうしても出たかったんだ」。

Such scenes stir powerful emotions in this sports centre, where evacuees are re-examining their own relationship with the Fukushima plant.

"I think you could say those nuclear workers have been brainwashed," said Keiichi Yamomoto, who used to visit the plant regularly for business. "Japanese people are used to focusing their whole lives on their company, and their company takes priority over their own lives."

He said the power company had a policy of locating nuclear facilities in sparsely populated areas with little local industry. Local people got jobs; the power company was able to increase its supply of electricity for Tokyo.

「そういった原発労働者は洗脳されてしまったとも言えるんですよ。日本人は会社に人生をあずけちゃいますからね」と山本ケイイチは言った。電力会社は人口が少なくて産業のない土地に原発を建設し、そういう地元の人を雇うのだ。そして、電気は、東京を供給されるのだ。

The Japanese government assented to the Fukushima plant; the prefecture government assented to it; even local people assented to the plant, when they took jobs as inspectors there, Yamomoto said. "It was a trade-off."

Now they are experiencing the consequences of that assent.

日本政府、地方政府、地元民がトレードオフの合意をしたが、その帰結がこのとんでもない有様だった。

People who built their lives around the nuclear plant without ever fully acknowledging its presence are now signing up for text updates of radiation readings from their home town.

Some evacuees in the sports hall say they cannot rely on the power company to give them accurate information. They are going to wait for the Japanese government to issue an all-clear before they consider returning home.

よくわからないまま原発周辺を生活の拠点としてしまった人たちは困った状況にある。

Others are wondering whether they are also somehow culpable in the disaster. Yoshizo Endo moved to live near the plant in 1970, when he became one of the first workers at the then newly opened Fukushima.

He spent more than 20 years as an inspector, undergoing regular safety exercises: fire drills, earthquake evacuations. But, he said, they never contemplated the prospect of a nuclear disaster. "Looking back, it's easy to say now that we should have thought of that," he said.

His wife, Tori, said the crisis at the plant, and the struggle of the nuclear workers, had made her increasingly uncomfortable: her husband had made a good living for years at the plant, and they were living on his pension even now. "I feel guilty," she said.

自分たちにも非があるかもしれないと考える人もいる。遠藤・ヨシゾは1970年に原発付近に引っ越してきて最初の原発労働者になったのだ。

遠藤は20年以上働き安全訓練もしてきたが、核災害がおきるなんてことは考えたこともなかった。「振り返ってみれば、考えてみるべきだった」と遠藤。

妻のトリは、「原発のおかげで長年良い暮らしをし、今では年金があるなんて、罪深く思う」と述べる。

Had Endo been called, he would have gone too, albeit as part of a team, he said. But he added: "I can't really do anything in this kind of situation. The only thing I know how to do is hold a thermometer."

Did he think the nuclear samurai would succeed in taming the reactors? "What will be will be," said Endo.

もし遠藤に呼び出しがかかったら、たとえアルバイトだとしても、また出かけてしまっただろうと遠藤は言う。しかし、次の言葉も付け加えた。「こういった状況で何でもやりますというわけにはいかない。なにしろ温度計のチェックしか知らないんだからね」

その遠藤に、「原発サムライは原子炉を沈静化できると思うか」と訊いてみた。すると、「なるようにしかならないね」と答が返ってきた。

以上

The truth about the Fukushima 'nuclear samurai'

Japan's 'nuclear samurai' are risking their lives to avert catastrophe, but many are manual labourers unequal to the task

福島の「原発サムライ」の真実ーー日本の「原発サムライ」は命をかけて大災害を防ごうとしているが、多くはそういった仕事にはふさわしくない肉体労働者である。

To a world that doesn't know him, Shingo Kanno is one of the "nuclear samurai" – a selfless hero trying to save his country from a holocaust; to his family, Kanno is a new father whose life is in peril just because he wanted to earn some money on the side doing menial labour at the Fukushima nuclear plant.

原発侍カンノ・シンゴの紹介。

カンノのことを知らない外部の人間から見たら、自らの命を危険にさらしながらも、ホロコーストから国を救おうとする勇敢な「原発サムライ」に見えるかも知れない。だが、彼の家族からしたら全然そういう者ではない。子どもが出来たので、お金がちょっと欲しかったという理由だけで、福島原発での奴隷的労働者に従事してしまった男にすぎなかったのだ。

A tobacco farmer, Kanno had no business being anywhere near a nuclear reactor – let alone in a situation as serious as the one that has unfolded after the 11 March earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

カンノはたばこ農民だった。原子炉なんかには無関係だったし、ましてや今日の原発事故には関係ない。

His great-uncle, Masao Kanno, said: "People are calling them nuclear samurai because people are sacrificing their lives to try to fix a leak. But people like Shingo are amateurs: they can't really help. It shouldn't be people like Shingo."

シンゴの大叔父のカンノ・マサオが言うには、「放射能漏れを防ごうと命をかけているので、世間は彼らを原発さむらいと呼ぶかもしれないが、本当は素人で本当に力になることは出来ないんだよ。シンゴみたいのがやるべきじゃないんだ」。

(←「原発サムライ」のような言葉はないはずだ。「原発ジプシー」という言葉はあるが)。

Masao Kanno is one of more than 500 people camped out on the hardwood floors of a sports centre in Yonezawa. The homes of most of them lie within 19 miles of the Fukushima plant. They worked at the plant, have family members who did, or passed it daily on the way to work or school.

カンノ・マサオは米沢(←福島県二本松市米沢のことだと思われる。場所的には原発とかなり近い)の体育館の床で仮住まいしている500人以上の避難者の一人だ。彼らの家の多くは福島原発30km以内にある。

(福島県二本松市米沢の地図)

(福島県二本松市米沢の地図)彼らは原発で働いたり、家族の中に働く者がいたり、または通勤・通学の時に近くを通り過ぎる。

Before, they rarely thought about the down side to that proximity; now it rules their lives. Many of their homes are inside the evacuation zone, with radiation 17 times higher than background levels and tap water too contaminated to drink.

訳は省略

Those with a close personal connection to the crisis, like Masao Kanno, are moved and grateful for the personal courage of the 500 or so workers still at the plant. But where Japan's prime minister and others have conjured up cardboard heroes, he sees a flesh-and-blood relation.

カンノ・マサオのように原発に個人的に関わり合いのある者からすれば、500人もの労働者が今な原発で奮闘している姿は大いに感動的だ。しかし、総理たちヒーローをでっち上げようとしているにすぎない。

Shingo Kanno, who had been hired to do construction work, was released from his duties at Fukushima soon after the declaration of a nuclear emergency. As the crisis at the plant worsened, and the Japanese government widened the evacuation zone, he moved his wife and his infant daughter to his in-laws, where they would be safer.

カンノは原発事故後には原発から解放され、妻子たちを安全な場所に避難させた。

He also helped evacuate his extended family from their home town of Minamisoma, which is within the 30km exclusion zone, to the sports centre and other shelters. Then, his relatives say, Kanno got a call from the plant asking him to go back to work.

危険地域の南相馬からの避難がすんだと思ったら、原発側から仕事に戻ってくるように電話があったのだ。

His whole family took turns getting on the phone to tell him not to go. They reminded him that he was a farmer, not a nuclear engineer, that he did not have the skills for such a sophisticated crisis. They said he should think of his responsibilities to his parents and his baby daughter.

"I told him: 'You have a family now. You shouldn't be thinking about the company – you should be thinking about your own family,'" said Masao Kanno.

家族全員が「原発なんかに戻るんじゃない、お前はただの農民にすぎないじゃないか。自分の家族の責任を考えなさい」といった。

But on Friday Shingo Kanno went back anyway. The family have not heard from him since.

In the meantime, the cult of the nuclear samurai has only grown. Japanese television aired an interview with a plant worker on Monday offering a harrowing insider's account of the struggle for the reactors.

しかし、カンノシンゴは金曜日に戻ってしまい、それ以来消息を聞いていない。原発サムライ・カルト(←原発労働者を英雄視するメディア像のことか)が大きくなっただけだ。日本のテレビは、原発労働者のインタビューを放映した。

The worker, his face hidden from view, described sirens blaring, billowing smoke, explosions so powerful the earth rumbled, water sloshing in the pool of spent atomic fuel. Then he touched on his own complicated emotions before pulling out of the plant. "The people left behind – I feel really sorry for them," the worker said. "It was a hard decision to make, but I had a strong feeling that I wanted to get out."

労働者は匿名で、原発の中の凄まじい状況を語った。それから、彼が原発に残してきてしまった同僚に対する複雑な感情に触れた。「残してきた人には本当にすまないと思う。辛い決断だったけれども、どうしても出たかったんだ」。

Such scenes stir powerful emotions in this sports centre, where evacuees are re-examining their own relationship with the Fukushima plant.

"I think you could say those nuclear workers have been brainwashed," said Keiichi Yamomoto, who used to visit the plant regularly for business. "Japanese people are used to focusing their whole lives on their company, and their company takes priority over their own lives."

He said the power company had a policy of locating nuclear facilities in sparsely populated areas with little local industry. Local people got jobs; the power company was able to increase its supply of electricity for Tokyo.

「そういった原発労働者は洗脳されてしまったとも言えるんですよ。日本人は会社に人生をあずけちゃいますからね」と山本ケイイチは言った。電力会社は人口が少なくて産業のない土地に原発を建設し、そういう地元の人を雇うのだ。そして、電気は、東京を供給されるのだ。

The Japanese government assented to the Fukushima plant; the prefecture government assented to it; even local people assented to the plant, when they took jobs as inspectors there, Yamomoto said. "It was a trade-off."

Now they are experiencing the consequences of that assent.

日本政府、地方政府、地元民がトレードオフの合意をしたが、その帰結がこのとんでもない有様だった。

People who built their lives around the nuclear plant without ever fully acknowledging its presence are now signing up for text updates of radiation readings from their home town.

Some evacuees in the sports hall say they cannot rely on the power company to give them accurate information. They are going to wait for the Japanese government to issue an all-clear before they consider returning home.

よくわからないまま原発周辺を生活の拠点としてしまった人たちは困った状況にある。

Others are wondering whether they are also somehow culpable in the disaster. Yoshizo Endo moved to live near the plant in 1970, when he became one of the first workers at the then newly opened Fukushima.

He spent more than 20 years as an inspector, undergoing regular safety exercises: fire drills, earthquake evacuations. But, he said, they never contemplated the prospect of a nuclear disaster. "Looking back, it's easy to say now that we should have thought of that," he said.

His wife, Tori, said the crisis at the plant, and the struggle of the nuclear workers, had made her increasingly uncomfortable: her husband had made a good living for years at the plant, and they were living on his pension even now. "I feel guilty," she said.

自分たちにも非があるかもしれないと考える人もいる。遠藤・ヨシゾは1970年に原発付近に引っ越してきて最初の原発労働者になったのだ。

遠藤は20年以上働き安全訓練もしてきたが、核災害がおきるなんてことは考えたこともなかった。「振り返ってみれば、考えてみるべきだった」と遠藤。

妻のトリは、「原発のおかげで長年良い暮らしをし、今では年金があるなんて、罪深く思う」と述べる。

Had Endo been called, he would have gone too, albeit as part of a team, he said. But he added: "I can't really do anything in this kind of situation. The only thing I know how to do is hold a thermometer."

Did he think the nuclear samurai would succeed in taming the reactors? "What will be will be," said Endo.

もし遠藤に呼び出しがかかったら、たとえアルバイトだとしても、また出かけてしまっただろうと遠藤は言う。しかし、次の言葉も付け加えた。「こういった状況で何でもやりますというわけにはいかない。なにしろ温度計のチェックしか知らないんだからね」

その遠藤に、「原発サムライは原子炉を沈静化できると思うか」と訊いてみた。すると、「なるようにしかならないね」と答が返ってきた。

以上