The family court personnel no doubt also consider themselves to be protecting the rights of the child — there might be assertions of abuse, the visitation might turn into an abduction (or counter-abduction); all sorts of terrible things could happen, so a presumption of guilt may be the safest course — for the court, at least, since it means it will not be blamed for any negative result. The ability of courts to be "safe" in this fashion would be jeopardized if visitation were any sort of fundamental right, since then the court would be participating in its infringement.

The same dynamic can be seen when it comes to full custody (shinken), or "parental authority," as it is officially translated. A standard textbook description of parental authority goes something like this: "although on its face shinken appears to have the character of parental rights (the 'ken' in shinken being written with the kanji for 'right,' as in jinken, human rights), it is more appropriate to think of it in terms of parental duties: the duties of parents to raise their children properly, and their duties to raise the next generation of citizens."

On first glance this seems like a perfectly wholesome way to think about the subject. Indeed, it is a formulation that probably comes naturally to jurists who no doubt see more than their fair share of dysfunctional families, bad parents and messed-up kids (family courts also have jurisdiction over juvenile criminal cases). Yet it is also a formulation that results in the subtle conversion of parental authority from something that parents can assert against the government on behalf of their children, into the means by which well-meaning judges and other government employees tell misguided parents what they are doing wrong and why they are bad parents.

However, the description of parental authority as a set of duties rather than rights actually ignores the wording of Japan's Civil Code, which sets forth a small number of rights as well as duties that come with parental authority, including the right to specify where one's children live, and the right to discipline them. Yet these rights do not seem to mean anything to family courts once it comes to divorce and custody — parents left behind when their children are removed by the other parent may find that even though they supposedly have custody, they do not even have the right to know where their children are, let alone decide where they live.

Indeed, the only time parental authority seems to involve rights is when it is terminated for abuse ("abuse of rights" is a basic concept in the law of Japan and some of the European countries on which it modeled much of its legal system). While there are formal procedures for terminating parental authority, they may not be necessary in practice: All it can take for a parent to lose all contact with their children, and be denied all information about their education or whereabouts, is an unproven allegation of abuse. Once a government agency has decided to act, whether or not you have "parental authority" may mean very little. The formal legal termination of parental authority after a married couple separates may be nothing more than a procedural afterthought to be noted in the family register, which, as already noted, is more about form than substance.

Thus, in my view, the fact that courts might be inclined to ignore Civil Code provisions that describe parental authority as including parental rights is understandable for the same reason that they might not be keen on referring to the Children's Rights Convention: It is probably personally and professionally more satisfying to tell other people what they should be doing than the other way around.

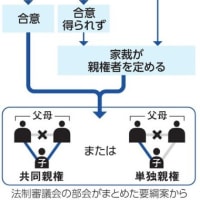

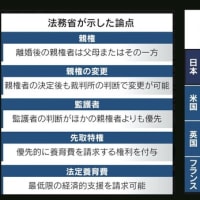

With rights being the principle way in which parents and other citizens could tell the courts and other government institutions what to do, their conversion into duties is also understandable. While in other countries courts provide a mechanism by which people assert their rights against bureaucracies, in Japan the courts tend to be more like bureaucracies themselves. The same logic may also explain why the Japanese government is able to advance plans to make it easier to terminate the rights of abusive parents at a time when growing calls for the adoption of joint custody, enforceable visitation and joining the Hague Convention on international child abduction remain unaddressed.

Consequently, parents and activists trying to address the problems of child abduction and parental alienation in Japan using arguments framed in terms of children's rights may not get very far with family courts or other bureaucracies. After all, they are the experts in the subject, and if you are in court they may presume you are a bad parent anyways. That being the case, they will tell you what is best for your child, not the other way around.

Furthermore, they may be able to do so without experiencing any apparent cognitive dissonance. An example of this is reported in a parents' group newsletter article about a recent case in the Saitama Family Court, in which the judge refused to award a father visitation on the grounds that it would cause his ex-wife emotional distress. In lieu of visitation, the judge decreed that the father should be sent three pictures of his child annually. On the court's web page, this same judge has posted a short column describing both how her family life is one of the foundations of her career, and her feelings of guilt about how her job keeps her from spending enough time with her two children. Three pictures a year, indeed . . .

Paradoxically, therefore, what may be needed in Japan is not more children's rights: it may have more than enough of those — they may just be being interpreted by the wrong people. Rather, what might actually be needed is stronger, more firmly defined parental rights — coupled with a clear understanding that it is first and foremost parents, not bureaucrats, who will decide what is best for their children before, during and after marriage, regardless of what it says in the family registry. Strong parents' rights are likely to be the key to stronger, more meaningful children's rights: Most parents — even the divorcing ones — are going to spend a lot more time thinking about what is best for their children than a judge or some other bureaucrat, no matter how well-intentioned.

Colin P. A. Jones is a professor at Doshisha Law School in Kyoto. Send comments and story ideas to community@japantimes.co.jp

We welcome your opinions. Click to send a message to the editor.

The Japan Times

(C) All rights reserved

The same dynamic can be seen when it comes to full custody (shinken), or "parental authority," as it is officially translated. A standard textbook description of parental authority goes something like this: "although on its face shinken appears to have the character of parental rights (the 'ken' in shinken being written with the kanji for 'right,' as in jinken, human rights), it is more appropriate to think of it in terms of parental duties: the duties of parents to raise their children properly, and their duties to raise the next generation of citizens."

On first glance this seems like a perfectly wholesome way to think about the subject. Indeed, it is a formulation that probably comes naturally to jurists who no doubt see more than their fair share of dysfunctional families, bad parents and messed-up kids (family courts also have jurisdiction over juvenile criminal cases). Yet it is also a formulation that results in the subtle conversion of parental authority from something that parents can assert against the government on behalf of their children, into the means by which well-meaning judges and other government employees tell misguided parents what they are doing wrong and why they are bad parents.

However, the description of parental authority as a set of duties rather than rights actually ignores the wording of Japan's Civil Code, which sets forth a small number of rights as well as duties that come with parental authority, including the right to specify where one's children live, and the right to discipline them. Yet these rights do not seem to mean anything to family courts once it comes to divorce and custody — parents left behind when their children are removed by the other parent may find that even though they supposedly have custody, they do not even have the right to know where their children are, let alone decide where they live.

Indeed, the only time parental authority seems to involve rights is when it is terminated for abuse ("abuse of rights" is a basic concept in the law of Japan and some of the European countries on which it modeled much of its legal system). While there are formal procedures for terminating parental authority, they may not be necessary in practice: All it can take for a parent to lose all contact with their children, and be denied all information about their education or whereabouts, is an unproven allegation of abuse. Once a government agency has decided to act, whether or not you have "parental authority" may mean very little. The formal legal termination of parental authority after a married couple separates may be nothing more than a procedural afterthought to be noted in the family register, which, as already noted, is more about form than substance.

Thus, in my view, the fact that courts might be inclined to ignore Civil Code provisions that describe parental authority as including parental rights is understandable for the same reason that they might not be keen on referring to the Children's Rights Convention: It is probably personally and professionally more satisfying to tell other people what they should be doing than the other way around.

With rights being the principle way in which parents and other citizens could tell the courts and other government institutions what to do, their conversion into duties is also understandable. While in other countries courts provide a mechanism by which people assert their rights against bureaucracies, in Japan the courts tend to be more like bureaucracies themselves. The same logic may also explain why the Japanese government is able to advance plans to make it easier to terminate the rights of abusive parents at a time when growing calls for the adoption of joint custody, enforceable visitation and joining the Hague Convention on international child abduction remain unaddressed.

Consequently, parents and activists trying to address the problems of child abduction and parental alienation in Japan using arguments framed in terms of children's rights may not get very far with family courts or other bureaucracies. After all, they are the experts in the subject, and if you are in court they may presume you are a bad parent anyways. That being the case, they will tell you what is best for your child, not the other way around.

Furthermore, they may be able to do so without experiencing any apparent cognitive dissonance. An example of this is reported in a parents' group newsletter article about a recent case in the Saitama Family Court, in which the judge refused to award a father visitation on the grounds that it would cause his ex-wife emotional distress. In lieu of visitation, the judge decreed that the father should be sent three pictures of his child annually. On the court's web page, this same judge has posted a short column describing both how her family life is one of the foundations of her career, and her feelings of guilt about how her job keeps her from spending enough time with her two children. Three pictures a year, indeed . . .

Paradoxically, therefore, what may be needed in Japan is not more children's rights: it may have more than enough of those — they may just be being interpreted by the wrong people. Rather, what might actually be needed is stronger, more firmly defined parental rights — coupled with a clear understanding that it is first and foremost parents, not bureaucrats, who will decide what is best for their children before, during and after marriage, regardless of what it says in the family registry. Strong parents' rights are likely to be the key to stronger, more meaningful children's rights: Most parents — even the divorcing ones — are going to spend a lot more time thinking about what is best for their children than a judge or some other bureaucrat, no matter how well-intentioned.

Colin P. A. Jones is a professor at Doshisha Law School in Kyoto. Send comments and story ideas to community@japantimes.co.jp

We welcome your opinions. Click to send a message to the editor.

The Japan Times

(C) All rights reserved