Why Cleaned Wastewater Stays Dirty In Our Minds

何故浄化された下水は、それでも汚いのか

感化思考(感染心理)非合理的ではあるが、人に備わった身を守る安全行動の一つでもあるそうだ

君子危うきに近寄らずという知恵だろう。この話をしたら、法律を学んでいる娘が面白い判例について話してくれた。

嫌がらせに食器におしっこをかけた犯人の罪状が「器物損壊」となった判例があるという、その判決理由は物理的に食器は破壊されていないが、食器本来の機能を使用者から奪ったという意味で損壊に等しいとしたもの。 話は変わるが、安全基準を下回っている放射能汚染土など、どこにでも捨てて(それこそ日本海溝にでも)よさそうなものだが、汚染というシミが感染心理に染みついているから、行き場を失う。民主主義とマスメディアは、安全地帯から声高に感染心理を後押しする。ちょっと飛躍しましたが根は同じところにあるような気がする。

by Alix Spiegel

August 16, 2011

Jeff Barnard/AP

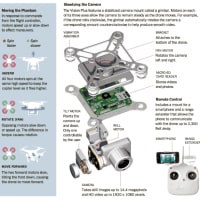

A boom sweeps around a tank at a sewage treatment plant in Coos Bay, Ore. Even though sewage water can be treated and cleaned, psychologists say getting the "cognitive sewage" out of the water is much more difficult.

オレゴン州、クースベイの下水処理施設でブームがタンクの水を掬って汚物除去をしている。

下水の水が処理され浄化されても、汚水から認知下水(飲料として受け入れられる水)を得るのはより大変だと心理学者は指摘する。

August 16, 2011

Brent Haddad studies water in a place where water is often in short supply: California.

Haddad is a professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. About 14 years ago, he became very interested in the issue of water reuse.

At the time, a number of California's local water agencies were proposing a different approach to the state's perennial water problems. They wanted to build plants that would clean local waste water — a.k.a. sewage water — and after that cleaning, make it available as drinking water. But, says Haddad, these proposals were consistently shot down by an unwilling public.

ブレント・ハダッドは水不足が頻繁な場所の水を研究している。 それはカルフォルニア州。 ハダッドはサンタクルズのカリフォルニア大学で環境学の教授をしている。約14年前、彼は水の再利用の問題に大変興味を持つようになった。

その時、幾つかのカリフォルニアの地域水道局(ローカル・ウォーター・エイジェンシー)が州の度重なる水問題に色々な対策を提案していた。 彼らは地域の排水(別名を下水)を浄化するプラントの建設を望んでいた。 そして、浄化した水を飲料水として利用できるようにと考えた。 しかし、ハダッドによると、これらの提案はことあるごとに、それを望まない住民によって潰された。

"The public wasn't really examining the science involved," Haddad says. "They were just saying no." This infuriated the water engineers, who believed that the public's response was fundamentally irrational, Haddad says.

"That's what I would hear at these water agency meetings," Haddad says, "these very frustrated water engineers saying, 'My public is irrational! They are irrational! They simply won't listen!"

For those unfamiliar with water reuse, it's a system by which water that's been used in your toilet, or sink, or shower is purified through a variety of technological processes that make it clean enough to drink. Then it's reused in the same location: It's used to water fields. It's put in reservoirs. It can also be used for drinking water.

It is quite difficult to get the cognitive sewage out of the water, even after the real sewage is gone.

「住民は、浄化に利用される科学技術を真面に検証してはいない。」「この方面の技術者たちは苛立ってこう述べている。“私たちの住民は理性的ではない。彼らは科学的ではない!彼らは単に耳を塞いでいるだけだ。」とハダッドは話す。

水の再利用に疎い方に改めて説明すると、それはトイレ、シンク、シャワーで使用された水を色々な技術的な処理を施して飲料に供することが出来るまでに浄化するシステムのことです。つまり、その水は元の場所で再利用されることになります。農業用水、貯水池、そして飲料用水にも使うことができます。

From the perspective of the water engineers Haddad was talking with, this kind of reuse was a no-brainer. The benefits were clear and the science suggested that the water would be safe. Clean Water Action, an environmental activist group, also supports reuse for drinking water, though it thinks there should be national regulatory standards.

But according to Haddad, no matter what the scientists or environmental organizations said, the public saw it differently: They thought that directly reusing former sewage water was just plain gross.

"A scientific answer is not going to satisfy someone who is feeling revulsion," says Haddad. "You have to approach it in a different way."

Which is why Haddad turned to a nonprofit called The WateReuse Foundation for funding for a study. He wanted to figure out more about the public's response to reused water, and for that he needed additional people. This was a job, Haddad concluded, for psychologists.

ハダッドが話した水利工学技術者の観点からは、この再利用は頭を悩ますような問題とは思えない。なぜなら利点は明確だし、科学的に水の安全性は保障されているのだから。環境問題の活動グループである、クリーンウォーター・アクションも、国家的基準設定があるべきとしながらも、この再利用計画を支持している。

しかし、ハダッドによると、科学者や環境団体がいくら支持しても、大衆は違った受け止め方をしているという。 彼らは、かつて下水だった、水の直接の再利用が単に気持ちが悪いと感じているのだ。

「科学的な回答では、嫌悪感を感じている人を説得することができないということです。」「ということは違うアプローチを考えなくてはならない。」とハダッドは言う

ハダッドがザ・ウォーターリユース・ファンデーションと呼ばれる非営利団体に対して、研究のための資金提供を呼びかけた理由はここにある。 彼は水の再利用に反応する大衆心理についてより詳らかにしたいと考えたが、そのためには専門の人々の助けを必要とした。これは心理学者の仕事だとハダッドは結論付けた。

Psychological Contagion 心理的感化

Carol Nemeroff is one of the psychologists whom Haddad recruited to help him with his research. She works at the University of Southern Maine and studies psychological contagion. The term refers to the habit we all have of thinking — consciously or not — that once something has had contact with another thing, their parts are in some way joined.

ハダッドが彼の研究補助として採用した心理学者の一人キャロル・ネメロフは南マイン大学で心理的感化について研究している。 そのチームは我々の考えることにおける「癖或いは習慣」に言及し、意識的である、ないにせよ、一旦、何かが他のものと接触すると、それらの部分としての特質は一緒のものとして、とにかく認識されると言っている。

How Wastewater Gets Cleaned どのようにして使用済水は浄化されるのか

In most large cities around the globe, sewage and wastewater gets processed at a treatment plant.

First, it passes through a filter to remove large materials like tree limbs, trash and leaves. Next up is the primary sedimentation tank, where sludge settles to the bottom and lighter liquids like grease, oil and soap rise to the top. The surface is skimmed off while the sludge is pumped away to a separate treatment facility.

Then it's on to another tank, where oxygen is bubbled in, enabling bacteria to break down any organic matter in the wastewater. After that comes another filtration — sometimes through sand or carbon.

地球上の殆どの大都市においては、下水と排水は処理工場で浄化される。

最初に、下水は木片、ゴミ、残物などを除去するためにフィルターを通過する。次に最初の沈澱池で汚泥を底に、油分やせっけんは表面に分離される。 分離された表面は掬い取られ、汚泥はポンプで他の分離施設に移される。

その後、もう一つのタンクに移行し、そこで酸素の泡が供給される。それにより下水中の有機物を活性化されたバクテリアが分解することができる。 そのあとで、更に細かい砂や木炭のフィルターを通過することになる。

During the final stage, the water is disinfected — by the addition of chlorine, hydrogen peroxide and other chemicals and by running it past ultraviolet lights. It's then drained into a nearby water supply, like a river, or pumped into the ground, where it is reintroduced into the below-ground water supply. Months to years later, water utilities extract the water from wells, which has now mixed with the wider supply. After standard testing and treatment for drinking water, this reclaimed water ends up in houses.

最後のフィルター透過中に塩素、酸化水素、その他の化学物質と紫外線照射により除菌される。 そして、近くの水供給用に回される、例えば河川水の中であり、地下水の中への再供給として。 数か月から数年後、水の供給施設は地下水から水を汲み上げることになるが、そこには再利用水も混じっていることになる。 飲料水としての標準テストと処理を施して、これらの水は家庭に供給されることになる。

— Andrew Prince

"It's a very broad feature of human thinking," Nemeroff explains. "Everywhere we look, you can see contagion thinking."

Contagion thinking isn't always negative. Often, we think that it is some essence of goodness that has somehow been transmitted to an object — think of a holy relic or a piece of family jewelry.

Nemeroff offers one example: "If I have my grandmother's ring versus an exact replica of my grandmother's ring, my grandmother's ring is actually better because she was in contact with it — she wore it. So we act like objects — their history is part of the object."

And according to Nemeroff, there are very good reasons why people think like this. As a basic rule of thumb for making decisions, when we're uncertain about realities in the world, contagion thinking has probably served us well. "If it's icky, don't touch it," says Nemeroff.

「それは人間の思考の非常に共通した特徴です。どこにおいても、我々はこの感化思考(感染心理)の現象を見ることができます。」と心理学者のネメロフは説明する。 感化思考はいつも否定的なものばかりとは限りません。しばしば、我々は対象物に何か善なるもののエッセンスが乗り移っていると考えることがあります。 神聖な遺物や家族の宝物を想像してみてください。

ネメロフは一つの例を挙げて説明してくれました。「もし私が祖母の指輪と、それと全く同じレプリカを持っていたとするでしょう。私にとっては祖母のリングが絶対に良いわけです、なぜならそのリングこそ祖母が接触していた・・・身に着けていたからです。 彼等の歴史は、その対象物の一部となっているのです。」

ネメロフによると、人々がそのように考えるにはちゃんとした理由があるということです。外界の不確かな現実に向き合って、物事を決定する基本的原則として、感化思考は多分機能し役だっているのです。 即ち「不快に感じたら触らない」ということです。

The researchers led by Haddad wanted to figure out more about how our beliefs about contagion in water work. And so they recruited more than 2,000 people and gave them a series of detailed questionnaires that sought to break down exactly what you would have to do to waste water to make it acceptable to the public to drink. The conclusion?

"It is quite difficult to get the cognitive sewage out of the water, even after the real sewage is gone," Nemeroff says.

Around 60 percent of people are unwilling to drink water that has had direct contact with sewage, according to their research.

But as Nemeroff points out, there is a certain irony to this position, at least when viewed from the perspective of a water engineer. You see, we are all already basically drinking water that has at one point been sewage. After all, "we are all downstream from someone else," as Nemeroff says. "And even the nice fresh pure spring water? Birds and fish poop in it. So there is no water that has not been pooped in somewhere."

ハダッドの研究チームは水再利用事業における感化思考について、更に明らかにしたいと考えました。そこで彼らは2000人事情の人に一連の詳細なアンケートを実施して、大衆が下水を飲み水とすることを受け入れるには、さらにどのようなことをすればよいのか研究しました。

結果ですか? 「それは、たとえ真の下水の部分を除去した後でも、下水から飲み水として受け入れられる水をつくりだすのは難しいということでした。」とネメロフは答えた。

彼らの調査によると、約60%以上の人が一度下水となった水を飲料水として飲むのは好まないと回答しています。

しかし、ネメロフは、この立場をとる人達に、ある皮肉(アイロニー)を指摘しています。少なくとも水利工学の技術者の観点でみると、我々は既に、基本的に飲料水の中にある時点で下水(汚水)だった過程を見ているのです。 結局のところ「我々は皆、どこかの下流で生きているのです。」「新鮮な良い純水に見える湧水でさえ、取や魚がその中で“うんち”をしています。「どこかで“うんち”に塗れてない水なんてものはないのです。」

Ridding Water Of Psychological 'Poop' 心理的な“うんち”を取り除く

Multnomah Falls in Oregon.

So what do you need to do to make reused water acceptable to the public?

Nemeroff says you need to change the identity of the water so that it's not the same water. "It's an identity issue, not a contents issue," she says. "So you have to break that perception. The water you're drinking has to not be the same water, in your mind, as that raw sewage going in."

One of the best ways to do that, Nemeroff and Haddad and their colleagues concluded, was to have people cognitively co-mingle the water with nature.

Apparently, if you have people imagine the water going into an underground aquifer, for example, and then sitting there for 10 years, the water becomes much more palatable to the public. It budges even those most unwilling to drink the water.

それでは再生水を大衆に受け入れられるようにするにはどうしたら良いのでしょうか?

ネメロフによると水のアイデンティティを変える必要があるとのこと、そうすることにより水は以前の水ではなくなるというのです。「これはコンテンツ(内容)の問題ではなく、アイデンティティ(出自)の問題なのです。」「だから、見方を変えなければなりません。 あなたの心のなかでは、飲んでいる水は、生の下水として流れていく水とは違うのです。」

ネメロフとハダッドのチームが辿り着いた、ベストな方策の一つは、人々に自然のなかで水を混ぜるという認識を持ってもらうことです。

水が地下の帯水層のとこまで行き、例えば、そこに10年も留まることを想像してみてください。その水はより受け入れられるものとなっているでしょう。 その水に最もこだわる人でさえ抵抗はないはずです。

This, Haddad says, is why people find it acceptable to get their water supply from their local river, even though that river water at one point mingled with the sewage of the town upstream. People see river water as natural.

But in fact, Haddad says, putting treated water back into nature can actually make it less clean.

"That's an interesting twist to all of this," Haddad says. "When you do introduce a river or even groundwater... you run the risk of deteriorating the water that's been treated. You can make the water quality worse."

In any case, say Nemeroff and Haddad, it's certainly true that our psychological relationship to water and our beliefs about contagion have an enormous impact on water policy in this country. We spend millions and millions of dollars for water that is cognitively, if not actually, free of contamination.

これは、人々が、たとえ水が上流の下水と混じっていようが、地域の川から取水することを受けいれる理由です。人々は川を自然として見ているのです。

しかし、実際は、処理水を自然に戻すことは、クリーンさを幾分損なっているのは事実なのです。「これは、全てにまつわる興味深い(循環の)屈曲なのですが、水を川や地下水から取り込むとき、人は既に処理された水を更に劣化させるリスクを背負っているのです。人は常に水を劣化させるものなのです。」とハダッドは言う。

いずれにせよ、水とそれに対する感化思考の間には心理的な関係が確かにあり、これが我が国の水政策に大きな影響力を持っています。我々は認識上、実際にそうなのだが、汚染されていない水に多大のお金をつぎ込んでいるのです。再利用せずに。

何故浄化された下水は、それでも汚いのか

感化思考(感染心理)非合理的ではあるが、人に備わった身を守る安全行動の一つでもあるそうだ

君子危うきに近寄らずという知恵だろう。この話をしたら、法律を学んでいる娘が面白い判例について話してくれた。

嫌がらせに食器におしっこをかけた犯人の罪状が「器物損壊」となった判例があるという、その判決理由は物理的に食器は破壊されていないが、食器本来の機能を使用者から奪ったという意味で損壊に等しいとしたもの。 話は変わるが、安全基準を下回っている放射能汚染土など、どこにでも捨てて(それこそ日本海溝にでも)よさそうなものだが、汚染というシミが感染心理に染みついているから、行き場を失う。民主主義とマスメディアは、安全地帯から声高に感染心理を後押しする。ちょっと飛躍しましたが根は同じところにあるような気がする。

by Alix Spiegel

August 16, 2011

Jeff Barnard/AP

A boom sweeps around a tank at a sewage treatment plant in Coos Bay, Ore. Even though sewage water can be treated and cleaned, psychologists say getting the "cognitive sewage" out of the water is much more difficult.

オレゴン州、クースベイの下水処理施設でブームがタンクの水を掬って汚物除去をしている。

下水の水が処理され浄化されても、汚水から認知下水(飲料として受け入れられる水)を得るのはより大変だと心理学者は指摘する。

August 16, 2011

Brent Haddad studies water in a place where water is often in short supply: California.

Haddad is a professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. About 14 years ago, he became very interested in the issue of water reuse.

At the time, a number of California's local water agencies were proposing a different approach to the state's perennial water problems. They wanted to build plants that would clean local waste water — a.k.a. sewage water — and after that cleaning, make it available as drinking water. But, says Haddad, these proposals were consistently shot down by an unwilling public.

ブレント・ハダッドは水不足が頻繁な場所の水を研究している。 それはカルフォルニア州。 ハダッドはサンタクルズのカリフォルニア大学で環境学の教授をしている。約14年前、彼は水の再利用の問題に大変興味を持つようになった。

その時、幾つかのカリフォルニアの地域水道局(ローカル・ウォーター・エイジェンシー)が州の度重なる水問題に色々な対策を提案していた。 彼らは地域の排水(別名を下水)を浄化するプラントの建設を望んでいた。 そして、浄化した水を飲料水として利用できるようにと考えた。 しかし、ハダッドによると、これらの提案はことあるごとに、それを望まない住民によって潰された。

"The public wasn't really examining the science involved," Haddad says. "They were just saying no." This infuriated the water engineers, who believed that the public's response was fundamentally irrational, Haddad says.

"That's what I would hear at these water agency meetings," Haddad says, "these very frustrated water engineers saying, 'My public is irrational! They are irrational! They simply won't listen!"

For those unfamiliar with water reuse, it's a system by which water that's been used in your toilet, or sink, or shower is purified through a variety of technological processes that make it clean enough to drink. Then it's reused in the same location: It's used to water fields. It's put in reservoirs. It can also be used for drinking water.

It is quite difficult to get the cognitive sewage out of the water, even after the real sewage is gone.

「住民は、浄化に利用される科学技術を真面に検証してはいない。」「この方面の技術者たちは苛立ってこう述べている。“私たちの住民は理性的ではない。彼らは科学的ではない!彼らは単に耳を塞いでいるだけだ。」とハダッドは話す。

水の再利用に疎い方に改めて説明すると、それはトイレ、シンク、シャワーで使用された水を色々な技術的な処理を施して飲料に供することが出来るまでに浄化するシステムのことです。つまり、その水は元の場所で再利用されることになります。農業用水、貯水池、そして飲料用水にも使うことができます。

From the perspective of the water engineers Haddad was talking with, this kind of reuse was a no-brainer. The benefits were clear and the science suggested that the water would be safe. Clean Water Action, an environmental activist group, also supports reuse for drinking water, though it thinks there should be national regulatory standards.

But according to Haddad, no matter what the scientists or environmental organizations said, the public saw it differently: They thought that directly reusing former sewage water was just plain gross.

"A scientific answer is not going to satisfy someone who is feeling revulsion," says Haddad. "You have to approach it in a different way."

Which is why Haddad turned to a nonprofit called The WateReuse Foundation for funding for a study. He wanted to figure out more about the public's response to reused water, and for that he needed additional people. This was a job, Haddad concluded, for psychologists.

ハダッドが話した水利工学技術者の観点からは、この再利用は頭を悩ますような問題とは思えない。なぜなら利点は明確だし、科学的に水の安全性は保障されているのだから。環境問題の活動グループである、クリーンウォーター・アクションも、国家的基準設定があるべきとしながらも、この再利用計画を支持している。

しかし、ハダッドによると、科学者や環境団体がいくら支持しても、大衆は違った受け止め方をしているという。 彼らは、かつて下水だった、水の直接の再利用が単に気持ちが悪いと感じているのだ。

「科学的な回答では、嫌悪感を感じている人を説得することができないということです。」「ということは違うアプローチを考えなくてはならない。」とハダッドは言う

ハダッドがザ・ウォーターリユース・ファンデーションと呼ばれる非営利団体に対して、研究のための資金提供を呼びかけた理由はここにある。 彼は水の再利用に反応する大衆心理についてより詳らかにしたいと考えたが、そのためには専門の人々の助けを必要とした。これは心理学者の仕事だとハダッドは結論付けた。

Psychological Contagion 心理的感化

Carol Nemeroff is one of the psychologists whom Haddad recruited to help him with his research. She works at the University of Southern Maine and studies psychological contagion. The term refers to the habit we all have of thinking — consciously or not — that once something has had contact with another thing, their parts are in some way joined.

ハダッドが彼の研究補助として採用した心理学者の一人キャロル・ネメロフは南マイン大学で心理的感化について研究している。 そのチームは我々の考えることにおける「癖或いは習慣」に言及し、意識的である、ないにせよ、一旦、何かが他のものと接触すると、それらの部分としての特質は一緒のものとして、とにかく認識されると言っている。

How Wastewater Gets Cleaned どのようにして使用済水は浄化されるのか

In most large cities around the globe, sewage and wastewater gets processed at a treatment plant.

First, it passes through a filter to remove large materials like tree limbs, trash and leaves. Next up is the primary sedimentation tank, where sludge settles to the bottom and lighter liquids like grease, oil and soap rise to the top. The surface is skimmed off while the sludge is pumped away to a separate treatment facility.

Then it's on to another tank, where oxygen is bubbled in, enabling bacteria to break down any organic matter in the wastewater. After that comes another filtration — sometimes through sand or carbon.

地球上の殆どの大都市においては、下水と排水は処理工場で浄化される。

最初に、下水は木片、ゴミ、残物などを除去するためにフィルターを通過する。次に最初の沈澱池で汚泥を底に、油分やせっけんは表面に分離される。 分離された表面は掬い取られ、汚泥はポンプで他の分離施設に移される。

その後、もう一つのタンクに移行し、そこで酸素の泡が供給される。それにより下水中の有機物を活性化されたバクテリアが分解することができる。 そのあとで、更に細かい砂や木炭のフィルターを通過することになる。

During the final stage, the water is disinfected — by the addition of chlorine, hydrogen peroxide and other chemicals and by running it past ultraviolet lights. It's then drained into a nearby water supply, like a river, or pumped into the ground, where it is reintroduced into the below-ground water supply. Months to years later, water utilities extract the water from wells, which has now mixed with the wider supply. After standard testing and treatment for drinking water, this reclaimed water ends up in houses.

最後のフィルター透過中に塩素、酸化水素、その他の化学物質と紫外線照射により除菌される。 そして、近くの水供給用に回される、例えば河川水の中であり、地下水の中への再供給として。 数か月から数年後、水の供給施設は地下水から水を汲み上げることになるが、そこには再利用水も混じっていることになる。 飲料水としての標準テストと処理を施して、これらの水は家庭に供給されることになる。

— Andrew Prince

"It's a very broad feature of human thinking," Nemeroff explains. "Everywhere we look, you can see contagion thinking."

Contagion thinking isn't always negative. Often, we think that it is some essence of goodness that has somehow been transmitted to an object — think of a holy relic or a piece of family jewelry.

Nemeroff offers one example: "If I have my grandmother's ring versus an exact replica of my grandmother's ring, my grandmother's ring is actually better because she was in contact with it — she wore it. So we act like objects — their history is part of the object."

And according to Nemeroff, there are very good reasons why people think like this. As a basic rule of thumb for making decisions, when we're uncertain about realities in the world, contagion thinking has probably served us well. "If it's icky, don't touch it," says Nemeroff.

「それは人間の思考の非常に共通した特徴です。どこにおいても、我々はこの感化思考(感染心理)の現象を見ることができます。」と心理学者のネメロフは説明する。 感化思考はいつも否定的なものばかりとは限りません。しばしば、我々は対象物に何か善なるもののエッセンスが乗り移っていると考えることがあります。 神聖な遺物や家族の宝物を想像してみてください。

ネメロフは一つの例を挙げて説明してくれました。「もし私が祖母の指輪と、それと全く同じレプリカを持っていたとするでしょう。私にとっては祖母のリングが絶対に良いわけです、なぜならそのリングこそ祖母が接触していた・・・身に着けていたからです。 彼等の歴史は、その対象物の一部となっているのです。」

ネメロフによると、人々がそのように考えるにはちゃんとした理由があるということです。外界の不確かな現実に向き合って、物事を決定する基本的原則として、感化思考は多分機能し役だっているのです。 即ち「不快に感じたら触らない」ということです。

The researchers led by Haddad wanted to figure out more about how our beliefs about contagion in water work. And so they recruited more than 2,000 people and gave them a series of detailed questionnaires that sought to break down exactly what you would have to do to waste water to make it acceptable to the public to drink. The conclusion?

"It is quite difficult to get the cognitive sewage out of the water, even after the real sewage is gone," Nemeroff says.

Around 60 percent of people are unwilling to drink water that has had direct contact with sewage, according to their research.

But as Nemeroff points out, there is a certain irony to this position, at least when viewed from the perspective of a water engineer. You see, we are all already basically drinking water that has at one point been sewage. After all, "we are all downstream from someone else," as Nemeroff says. "And even the nice fresh pure spring water? Birds and fish poop in it. So there is no water that has not been pooped in somewhere."

ハダッドの研究チームは水再利用事業における感化思考について、更に明らかにしたいと考えました。そこで彼らは2000人事情の人に一連の詳細なアンケートを実施して、大衆が下水を飲み水とすることを受け入れるには、さらにどのようなことをすればよいのか研究しました。

結果ですか? 「それは、たとえ真の下水の部分を除去した後でも、下水から飲み水として受け入れられる水をつくりだすのは難しいということでした。」とネメロフは答えた。

彼らの調査によると、約60%以上の人が一度下水となった水を飲料水として飲むのは好まないと回答しています。

しかし、ネメロフは、この立場をとる人達に、ある皮肉(アイロニー)を指摘しています。少なくとも水利工学の技術者の観点でみると、我々は既に、基本的に飲料水の中にある時点で下水(汚水)だった過程を見ているのです。 結局のところ「我々は皆、どこかの下流で生きているのです。」「新鮮な良い純水に見える湧水でさえ、取や魚がその中で“うんち”をしています。「どこかで“うんち”に塗れてない水なんてものはないのです。」

Ridding Water Of Psychological 'Poop' 心理的な“うんち”を取り除く

Multnomah Falls in Oregon.

So what do you need to do to make reused water acceptable to the public?

Nemeroff says you need to change the identity of the water so that it's not the same water. "It's an identity issue, not a contents issue," she says. "So you have to break that perception. The water you're drinking has to not be the same water, in your mind, as that raw sewage going in."

One of the best ways to do that, Nemeroff and Haddad and their colleagues concluded, was to have people cognitively co-mingle the water with nature.

Apparently, if you have people imagine the water going into an underground aquifer, for example, and then sitting there for 10 years, the water becomes much more palatable to the public. It budges even those most unwilling to drink the water.

それでは再生水を大衆に受け入れられるようにするにはどうしたら良いのでしょうか?

ネメロフによると水のアイデンティティを変える必要があるとのこと、そうすることにより水は以前の水ではなくなるというのです。「これはコンテンツ(内容)の問題ではなく、アイデンティティ(出自)の問題なのです。」「だから、見方を変えなければなりません。 あなたの心のなかでは、飲んでいる水は、生の下水として流れていく水とは違うのです。」

ネメロフとハダッドのチームが辿り着いた、ベストな方策の一つは、人々に自然のなかで水を混ぜるという認識を持ってもらうことです。

水が地下の帯水層のとこまで行き、例えば、そこに10年も留まることを想像してみてください。その水はより受け入れられるものとなっているでしょう。 その水に最もこだわる人でさえ抵抗はないはずです。

This, Haddad says, is why people find it acceptable to get their water supply from their local river, even though that river water at one point mingled with the sewage of the town upstream. People see river water as natural.

But in fact, Haddad says, putting treated water back into nature can actually make it less clean.

"That's an interesting twist to all of this," Haddad says. "When you do introduce a river or even groundwater... you run the risk of deteriorating the water that's been treated. You can make the water quality worse."

In any case, say Nemeroff and Haddad, it's certainly true that our psychological relationship to water and our beliefs about contagion have an enormous impact on water policy in this country. We spend millions and millions of dollars for water that is cognitively, if not actually, free of contamination.

これは、人々が、たとえ水が上流の下水と混じっていようが、地域の川から取水することを受けいれる理由です。人々は川を自然として見ているのです。

しかし、実際は、処理水を自然に戻すことは、クリーンさを幾分損なっているのは事実なのです。「これは、全てにまつわる興味深い(循環の)屈曲なのですが、水を川や地下水から取り込むとき、人は既に処理された水を更に劣化させるリスクを背負っているのです。人は常に水を劣化させるものなのです。」とハダッドは言う。

いずれにせよ、水とそれに対する感化思考の間には心理的な関係が確かにあり、これが我が国の水政策に大きな影響力を持っています。我々は認識上、実際にそうなのだが、汚染されていない水に多大のお金をつぎ込んでいるのです。再利用せずに。

※コメント投稿者のブログIDはブログ作成者のみに通知されます