Imperialists for “Human Rights”

by Bécquer Seguín

“Human rights” has become the language of Western aggression.

via mozu

いろんな論点があるので、他の記事で補うと、

Last Utopia: Human Rights in History. By

Samuel Moyn. (Cambridge: Belknap Press of

Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 337. $27.95

cloth.)

人権だ!、じゃんけんだ!とこうるさくいうようになったのはごく最近のことで、そもそも人権というのは自国政府との関係で政府が保障してくれる国民の権利であって、政府を超えて、人権だ、じゃんけんだ!と言われ始めたのは、脱植民地主義などのユートピアが失敗に終わり、それに幻滅した人々が、最後のユートピアとして、国家を乗り越えて請求できるものとして、人権だ、じゃんけんだ、と言い始めたのである、と。

で、最初の記事は、

いわゆる人権が、アメリカや西側諸国の政治のために恣意的に使われ、アメリカが数千の無辜の民を殺しても、罪に問われないが、イラクやソマリアやリビアの場合には軍事介入の理由になるのだ、と。

あとは、この本の著者のいわゆる人権批判は有効なところがあるけど、マルクス主義による批判にももっと耳と傾けるべきだ、みたいなかんじかな。

こっちはNYTによるレビュー

New Birth of Freedom

By BELINDA COOPER

Published: September 24, 2010

NYTでは、ニュルンベルク裁判での人権の役割を軽視しているし、また、人権がいまでも、政府を通じて保障されるものであることを見落としているみたい、な批判がある。

それはいいとして、慰安婦問題をみても、女性の人権なんて、自国が加害者の場合は屁とも思っていないわけですね。世界中の人権そのものを公平に、重要視しているわけではない。、

まあ、欧米が、他国について人権、じゃんけんと声高にいうときは、それ以外に政治目的があるのだろうな、と思ったほうがいいかもしれませんね。

by Bécquer Seguín

“Human rights” has become the language of Western aggression.

via mozu

いろんな論点があるので、他の記事で補うと、

Last Utopia: Human Rights in History. By

Samuel Moyn. (Cambridge: Belknap Press of

Harvard University Press, 2010. Pp. 337. $27.95

cloth.)

What are human rights? !e question of definitions too often elicits vague responses. Moyn, in contrast, is pithy and precise. He does not catalogue specific rights but defines human rights in terms of the way they make their claims. For most of modern history, Moyn contends, the claimants of rights have taken the nation-state to be a guarantor of rights and an agent of their fulfillment. What makes contemporary human rights so novel and distinct, Moyn proposes, is the claim, which became

widespread in the 1970s, that human rights precede and supersede the modern nation-state. So how did this come to pass?

!e rise of human rights in the 1970s depended on a vigorous, transnational social movement that brought the claims of universal rights to the fore. Moved by optimistic visions of a law-girded world, the movement for human rights proceeded from what Moyn calls a “utopian” vision.!e Amnesty International volunteers who wrote letters to despots on behalf of prisoners of conscience were concerned with individuals, but they also sought to change the world. !ey imagined a universal law, binding the power of governments, subjecting them to its writ, and exposing misdeeds to humankind.!is, Moyn writes, was a strident ambition and a

novel one—so much so that to speak of human rights prior to the 1970s is to indulge in anachronism.

Why was it that the 1970s brought a new vocabulary of human rights? !e question of origins,Moyn argues, is really a question of “displacement” (p. 116); it was the failure of other utopian schemes for the betterment of humankind that opened up the space for human rights.!e great epic of early postwar history, Moyn argues, was not the rise of human rights—a marginal theme—but the ascent of postcolonial nationalism, another utopia promising historical deliverance.!e postwar ascent of the sovereign state,

of course, inhibited rights claims that were transnational and antisovereign in nature. Only in the 1970s, as the legitimacy of postcolonial projects crumbled in an era of coups and military strongmen, did the space for human rights expand. In the Soviet sphere, meanwhile,Marxist-Leninism’s crisis of legitimacy during the 1970s cracked open the door to human rights, which Western activists helped to push further ajar.

For the disillusioned, human rights offered an alternative utopia, an opportunity for redemption and ethical purification.!is, Moyn suggests, was the real the appeal of the “anti-politics” that human rights proffered.Yet the notion of anti-politics is too often a fiction, Moyn concludes, and not necessarily a very useful one. As human rights have matured and as the appetites of their proponents have expanded, they have become burdened by the baggage—of politics, ideology, and interest—that they claimed to repudiate in the first place.

人権だ!、じゃんけんだ!とこうるさくいうようになったのはごく最近のことで、そもそも人権というのは自国政府との関係で政府が保障してくれる国民の権利であって、政府を超えて、人権だ、じゃんけんだ!と言われ始めたのは、脱植民地主義などのユートピアが失敗に終わり、それに幻滅した人々が、最後のユートピアとして、国家を乗り越えて請求できるものとして、人権だ、じゃんけんだ、と言い始めたのである、と。

で、最初の記事は、

Moyn’s goal in The Last Utopia is to specify, not broaden, the history of human rights. Against scholars who look back centuries to find its origins, he argues human rights only appeared with the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in 1948. And even then, it entered like a whisper into an international political and legal scene marked by demands for Holocaust reparations, the establishment of the welfare state, and an end to colonialism.

Much to Moyn’s chagrin, many in the US and elsewhere believe that human rights violations — anything that deprives an individual of “the right to life, liberty and the security of person,” according to Article Three of the Universal Declaration — ought to be handled by an international legal system that can override national laws. And when that kind of enforcement doesn’t work, it’s up to the most powerful states to intervene on behalf of violated citizens, who almost always come from poorer, “failed” states.

Though not entirely ignoble, such logic is invariably used selectively. Human rights NGOs and the UN may sporadically “condemn” the US and Western European countries, but it ultimately grants them impunity while judging others, like Venezuela, perpetual violators. The Westphalian assumptions that motivated the Universal Declaration — that the West or Western-friendly nations should never use international law to breach each other’s national sovereignty — also authorized the spate of US military interventions in the 1990s in places like Iraq, Somalia, Sierra Leone, and Yugoslavia.

During that time the US not only slaughtered thousands of innocent civilians through mass bombing raids, but also supported the leadership of right-wing war criminals like Agim Ceku. Much the same is happening today in places like Libya, where calls back in 2011 for intervention based on the Qaddafi government’s human rights violations have precipitated the current humanitarian crisis. And still, human rights-oriented interventionism blithely flourishes.

いわゆる人権が、アメリカや西側諸国の政治のために恣意的に使われ、アメリカが数千の無辜の民を殺しても、罪に問われないが、イラクやソマリアやリビアの場合には軍事介入の理由になるのだ、と。

あとは、この本の著者のいわゆる人権批判は有効なところがあるけど、マルクス主義による批判にももっと耳と傾けるべきだ、みたいなかんじかな。

こっちはNYTによるレビュー

New Birth of Freedom

By BELINDA COOPER

Published: September 24, 2010

NYTでは、ニュルンベルク裁判での人権の役割を軽視しているし、また、人権がいまでも、政府を通じて保障されるものであることを見落としているみたい、な批判がある。

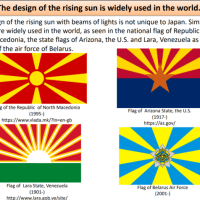

それはいいとして、慰安婦問題をみても、女性の人権なんて、自国が加害者の場合は屁とも思っていないわけですね。世界中の人権そのものを公平に、重要視しているわけではない。、

まあ、欧米が、他国について人権、じゃんけんと声高にいうときは、それ以外に政治目的があるのだろうな、と思ったほうがいいかもしれませんね。