Instead of jump-starting a conversation about the most effective approach to cancer research, Time distorted it beyond recognition. It’s certainly not the first time that’s happened. It’s been more than four decades since President Nixon signed the National Cancer Act of 1971, promising cancer sufferers that their “hopes will not be disappointed.” In 1998, mortality rates for all types of cancer had actually increased slightly, from 200.73 to 200.82 deaths per 100,000 people. That didn’t stop the New York Times from running Gina Kolata’s embarrassing front-page “special report,” which quoted James Watson as saying a researcher at Children’s Hospital in Boston would “cure cancer in two years.” Watson claimed he said no such thing―“When I read her article, I was horrified,” he told a reporter at the time.

Timeの4月1日付けの表紙、

癌をいかに治療するか ドリームチームのおかげで、もっと早く、よりよい結果を得ることができるようになった、とあるが、これは嘘であり、非常に苦しい治療を受けている患者にとっては残酷である、と。エイピリルフール記事ではないでしょうね?

Time とか、New York Times なんか、と聞くと、すごい権威がありそうですけど、産経やスポニチとかとそれほど変わらないのかもしれませんね。

フォロー

Mulboyne

@Mulboyne

Aya Tsukioka (vending machine dress) is back. This time with some office camouflage outfits: http://news.livedoor.com/article/detail/7541202/ …

Mulboyne

@Mulboyne

@Durf I do think the pigeon masks on the third page look a little unrealistic. I suspect they aren't being entirely serious.

返信 リツイート お気に入りに登録 その他

2013年3月29日 - 2:28

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript" src="http://kwout.com/cutout/a/34/74/x5a_bor.js"></script>

3ページ目の鳩をみるまでもなく、これは遊びでしょう。多少溶け込むかもしれないが、隠れるための役にはまったくたっていない。

これ、以前、NYTがトンデモ記事書いたやつですね。

、

Fearing Crime, Japanese Wear the Hiding Place

犯罪を恐れ、日本人は、隠れ家を着る

日本人は着る、となっているのに、

「瞬間自動販売機スカート」と言うものみたいです。今まで知りませんでしたが東京でちらほらと個展を開催されていたみたいです。

海外のメディアによればこの「忍者スカート」は女性が犯罪に遭うかもしれないという恐怖心を和らげるように願って考えたというデザインと報じています。

大抵の日本人は知らない。

そもそも

月岡さんも指摘しているように、犯罪者に追いかけられているときに素早く「自販機」に変身させることができるのかは疑問で、さらに、当然蛍光灯がついていないため夜だとバレてしまう危険性もあるのだ。

そもそも「瞬間自動販売機スカート」は防犯グッズではなく芸術作品で、こうしたインタビューへの回答も月岡さんのジョークなのかもしれない。

要するに、これも 遊び、である。

この記事は別に残酷な嘘ではありませんけど、間抜けな誤報 だったわけで、ジャーナリズムの教科書に恥かしい笑い話として掲載してもらいたいものです。

日本関連の英語記事ってわりにこんなのが多くて、日本人に対する偏見は大半、こうして日本関連記事を書く、日本人、外国人の記者が捏造したものであります。

もちろん、日本の記者やメディアも、海外について同様な罪を犯しているわけで、ちゃんと注意してもらいたいものであります。

Beyond multiculturalism

While multiculturalism aims for unity, we are still working towards tolerance - a fact made painfully clear post-9/11.

Last Modified: 28 Mar 2013 12:55

Maryana Hrushetska

The price tag for multiculturalism has been the ascent of rigid identity politics, where cultural groups proclaim either their "specialness" or "victimhood", continually setting themselves apart from others.

The result has been a backlash from those in the cultural majority and rivalry for resources amongst minorities. While multiculturalism aimed for unity, in truth we are still working towards tolerance - a fact made painfully clear in a post-9/11 landscape where fear is the dominant cultural marker and "the Other" is usually to blame.

A fundamental flaw of multiculturalism is the view that the broad concept of culture is pure and static. It elevates individual cultures as distinct self-contained universes when in reality they have long interacted and influenced one another.

The insight of this wise 9-year-old girl made me question the impact of my curatorial practice. Was I creating common ground or reinforcing "Otherness"? Would giving voice to the disenfranchised create understanding or distance? How could I contribute to unity while leaving room for uniqueness?

The insight of this wise 9-year-old girl made me question the impact of my curatorial practice. Was I creating common ground or reinforcing "Otherness"? Would giving voice to the disenfranchised create understanding or distance? How could I contribute to unity while leaving room for uniqueness?

これはちょっと面白かった。

そこで、引用されている本のレビューを2、3みてみると、

Book Review: Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, by Kwame Anthony Appiah

Having said this, the desire to eliminate differences is not a prima facie sign of cosmopolitanism. After all, fundamentalists who seek to make everyone conform to their religion (to the point of murdering those who resist) do wish to eliminate difference, but are certainly not cosmopolitans. The cosmopolitan ideal is far from this: it is to temper the respect for difference, with a respect for human beings. Its prescriptive element therefore does not just preach tolerance, but also generates obligations towards strangers

A Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers

By Kwame Anthony Appiah

W. W. Norton & Company

196 Pages

$23.95

By Jenny Jin

Though Appiah wants peace between countries, such peace should not come at the price of losing a healthy sense of nationalism and cultural pride. Appiah respects local customs and beliefs, challenging his readers to think about what these customs and beliefs mean to the people who hold them.

Indeed, some of the best writing in the book appears when Appiah describes his Asante family in Ghana. Because Appiah has the benefit of real experience, his stories about Ghanaian customs and beliefs are not simply novelty items, but human stories told to make a point. Appiah takes pains to show that Asante beliefs about spirits and witchcraft are as common and natural in Ghanaian society as Christian beliefs about God and angels in the United States. A cosmopolitan, a citizen of the world, would not be content to simply brush off Asante beliefs as "their way" and continue down his or her own, but would take the time to talk to a Ghanaian and try to understand how he or she thinks. Cosmopolitism is, above all, a philosophy of open conversation.

his is because he believes that all cultures already agree on certain moral universals. As he points out, most everyone accepts that universal wrongs, like murder, rape, and incest are, well, wrong. And most of us can very well distinguish between these sorts of absolute wrongs and the mere taboos of our local culture, like not being allowed to eat red peppers on Wednesdays or to shake a woman's hand when she is menstruating. It is the ability to make this distinction that allows one to sit down with someone from across the world and agree with him or her about what it means to be a good human being.

Local cultures have always changed and adapted in response to the influence of invading foreigners (whether military or commercial). To resist natural cultural evolution would be anticosmopolitanism of the most futile kind. A second related chapter continues this argument as it pertains to "cultural property." Appiah points out that in a global culture, works of ancient and historical significance belong to everyone, not to any single country or culture. It is absurd for countries less than a century old to claim that all ancient artifacts unearthed within their borders are national property. "Whose culture is it, anyway?" Appiah asks rhetorically.

Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers

This cosmopolitan ethic, which he traces from the Greek Cynics and through to the U.N.'s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, must inevitably balance universals with respect for particulars. This balance comes through "conversation," a term Appiah uses literally and metaphorically to signal the depth of encounters across national, religious and other forms of identity. At the same time, Appiah stresses conversation needn't involve consensus, since living together mostly entails just getting used to one another.

多文化主義ってのは、もう、限界がきているみたいですね。

自分たちと歴史や社会的条件が違う習慣、それを身につけた人々とどう接していくか、というのが、人々の交流が盛んになった現代世界の大きな一つの問題なわけですね

で、原理主義者というのは、他者との違いに接して、それを抹殺し、自分たちの原理を生活の隅々までひろく普及させようとする。

タリバンとかなんとかが原理主義者とか言われていますけど、キリスト教原理主義者もおり、また、欧米中心主義者、あるいは、帝国主義者というのは、たいてい、同時に、原理主義的なところがある。

要するに、自分たちの原理、視点が正しく、自分たちが違和感を感じる人々、そして、その人々がやっていることは間違っていて、それを正していかなくてはいけない、という態度が先行しているのであります。違いを違いとして尊重できない。

多文化主義というのは、これとは違って、違いは尊重するものの、各々の文化、あるいは民族が、固定的、自己充足的、他でもない己の独自性からなっているという前提のもと、お互い、統合できずに、バラバラになってしまう。

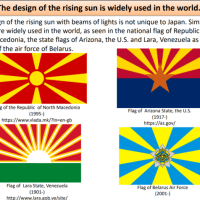

自分たちの民族性を被害者として自己規定して、それをもって、自己定義にしてしまうような民族もあるわけで、そういって憚らない大統領がいたことが記憶に新しいわけです。で、それだと、加害者と規定された国家と平行線をたどるだけになってしまう。

しかし、文化とか民族ってそんな純粋なものはそもそもなく、どれもが他者からつねにすでに影響を受けいる。

で、そこで、登場するのがコスモポリタ二ズムで、これは、普遍性・共通性を前提に各々の文化・民族の特殊性を尊重するんだ、と。

多文化主義、相対主義のように、根本的に違う、ということが前提ではなく、根本的には、共通性があるんだ、ということが大前提である、と。

そして、同じ人間だから、地球の裏の人間についても倫理的な義務があるんだ、と

人を殺しちゃいけないとか、約束をやぶっちゃいけない、などとういことはわりに普遍的な倫理法則なわけです。その上で、歴史や社会条件が違うから、特殊性がある。その特殊性も、たんに、ナショナリズムといって否定するのではなく、やはり、違いとして、尊重する。

違いの尊重の仕方ですけど、それは、開かれた会話を通じた、”慣れ”なんだ、というわけでしょうかね、レビューだけですから、詳しくはわかならいですけど、そんな感じじゃないでしょうか。

細かな議論はちょっとわからないですけど、大前提として、われわれはおおよそ同じ人間性をもっており、根本的な価値観というのも、かなり似通っているんだ、日常生活における信念体系なんかも、それほどちがったものじゃない。その大雑把な共通性を前提に、違いが目立ったりするわけですけど、この根本が同じ、とみるか、根本的に違う、とみるか、によって効果的にはかなり違ってくる。

欧米の記者たちの多くは、日本人、東洋人に対して、根本的に不気味な不安感があり、おかしい、変だ、奇怪だ、おれらとは根本的に違っている、という前提がある場合が多い。それを前提に記事を書いているわけですね。

外国人の記者の場合は、実際に日本人と接して会話しないで、他の英語の記事やら本を読んで固定観念的に記事を書く。英語圏で雇われている日本人の記者が日本について書くときも、上司や周囲がそんな感じなせいか、無意識に迎合、conform してしまって、固定観念、決まりきった枠組みで書く。

翻って、海外についての日本人による報道をみると、日本人の記者も、現地にいながら、現地の人に接触しているような形跡がある記事からはあまりみられない。英語記事の要約、翻訳みたいなのばっかであるーーーまあ、そんな印象をぼくはもっています。

これでは、世界はバラバラになってしまうのは当然ですね。