いくつか権利に関する記事を読んで(*)いたら、なんや、

Rights stanford.edu

これがよくまとまっているやないけ、と思ってメモ風にまとめた。

定義

権利とは、自分が何らかの行為をする、あるいは、何らかの状態にある資格であり、また、他人に何らかの状態をさせ、あるいは、何らかの状態にする資格である。

構造・要素

権利には自由・請求権などの要素からなる内部構造がある。

一次的規則ー何かをし、あるいは何かをしないようにする規則

自由権

A has a privilege to φ if and only if A has no duty not to φ.

Aは φ する自由権を有する⇔ Aは φ をしない義務がない

請求権

A has a claim that B φ if and only if B has a duty to A to φ

AはBが φ する請求権を有する⇔BはAにφする義務がある。

二次的規則 一次的規則を発生・変更・移転・消滅させる規則

権限

A has a power if and only if A has the ability within a set of rules to alter her own or another's Hohfeldian incidents.

Aは権限がある ⇔Aは規則の範囲内で自分あるいは他人の法律関係を変更する能力がある。

例

船長は船員にデッキの掃除を命令する権限を行使することによって 船員にある義務を発生させ、ある自由を消滅させる

諾約者はある約束をする権限を行使することで、受約者にあることをする義務を発生させる。

家主はお隣さんを招待する権限を行使することで、彼が家に入らない義務を放棄する。

司令官は船長の権限を剥奪する権限がある。

免責権

B has an immunity if and only if A lacks the ability within a set of rules to alter B's Hohfeldian incidents.

Bは免責権がある。⇔AにはBの要素を変更する能力がない。

例

議会は国民が十字架の前に跪かせる能力がない。⇔国民は(跪かない)免責権がある。

自由権・請求権・権限・免責権などの原子的要素は単独で、権利になりうるが、ある構造をなして、分子的権利を構成することもある。

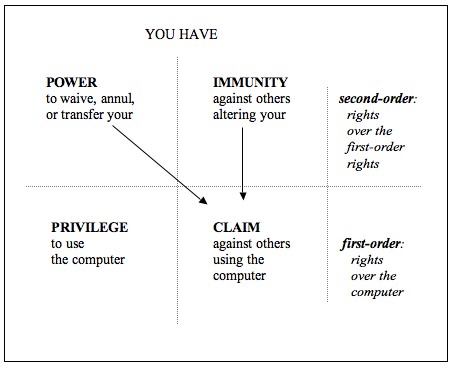

例 所有権

Aはコンピューターの所有権がある。

⇔

一次的権利

Aはコンピューターを使う自由権があり、使わない義務はない。

Aは他人がコンピューターを使わせない請求権があり、他人は使わない義務がある。

二次的権利

Aは他人がこのコンピューターを使わせない請求権を放棄して、義務を解除する権限があり、所有権に対する請求権を放棄し、あるいは、移転する権限がある。また、

他人がAのこのコンピューターの所有権に関する請求権を消滅・移転させない、免責権がある。

自由権・権限は権利の保持者が何かをする能動的権利であり、請求権・免責権は他人に何をしてもらう受動的権利である。

他人から介入されない資格は否定的権利、また、何らかの財やサービスを受ける資格は肯定的権利である。

機能ーー権利の保持者に対して何をするか

意志説

権利の保持者は権利によって、他人の義務について支配権を与えられる。コンピューターの所有権をもっている人は、他人の義務を消滅・移転などさせる権限をもっている。いわば、コンピュータの”統治者”であり、自分の裁量で、他人がそのコンピューターに触ることを許可することができる。受約者は、諾約者の義務を解除することができる。要するに、他人がある仕方で行動する義務を支配する能力が授与されているのである。

批判

奴隷にならないことなど、放棄できない権利もある。

幼児や動物などの権利を説明できない。

利益説

権利の保持者は、権利によってその利益が促進されるのである。所有者が選択肢を持っているからではなく、所有権によって所有者の利益が高まるのである。受約者は諾約者が約束を守ることによって利益がある。

批判

利益関係はあっても権利がない場合もある。例 宝くじにあたった配偶者の賞金を支払ってもらう利益

ある裁判官が被告人に死刑を宣告するどんな利益があってもだからといって、その権限が正当化されるわけではなく、権限とは無関係

権利と理由

切り札としての権利

権利を持っているということは、ある社会政策をくつがえす切り札として規範的強制力があり、権利を支える理由は、他の理由よりも強力である。

もっとも、

権利同士では、 トランプの切り札ジャック(11)は7や3を負かすように、例えば、信号での黄色が点灯している場合、歩行者の歩行する権利の方が、赤信号に直面している自動車が運行する権利より優先する。もっとも、両者の権利は救急車が走行する権利には及ばない、というように権利同士では優先関係がある。

とすれば、なによりも最優先される絶対的権利があるか、という疑問がわくが、例えば、殺害されない権利を絶対的な例として論者もいる。もっとも、100万人を救うためには1人の犠牲は致し方ないのではないか、その意味ではそうした権利も絶対的とはいえないのではないか、という論者もいる。

ある権利が他の権利に優先する場合があるとすれば、衝突する場合もあるようにも思える。例えば、人々がデモする権利は政府の公共の秩序を守る権利と衝突するようにも思える。

これに対して、例えば、デモする権利というのは、実際には、他人の生命財産を侵害しない、致死病を蔓延させない など の場合に行使できる権利であり、政府の公共の場所に対する権限も、平和的デモを阻害しないで、致死病の蔓延につながらない など の場合に限り行使できる権利である、といった具合に条件を特定すればジグゾーパズルが断片同士がぶつかりあわずうまく組みあうように権利同士も衝突することはないのだ、という論者もいる。これに対して、「など」というのがくせ者で、そもそもすべての条件を列挙して特定化することはできない、と反論するものもいる。

権利は衝突する場合だけでなく、ある権利が他の権利を支える場合もある。

一方の権利を認めて他方の権利を認めないと実際的、論理的に不整合になる場合、他方は一方を強く支え、他方が一方の権利に本質的と言えないまでも有益な場合には、弱い支えになっている。例えば、身体上の安全が確保される権利は集会の自由を強く支え、教育を受ける権利は、公正な裁判を受ける権利の弱い支えになっている。また、同じ権利でもそれが強化されれば、他の権利の強い支えになるが、いい加減だと弱い支えにしかならない。適正手続の権利は、平等に扱われる権利の支えているが、しかし、適正手続きの権利がいい加減に施行されていると、支えは軟弱なものにならざるえない。

権利の正当化

1)地位説

ある地位・属性を有するからその権利は尊重される。

批判

地位の根拠が宗教的、形而上学的で不確かである。

不可侵の権利についてどれがそれか、合意がない。

2)手段説

権利が尊重されるのは、それが全体の福利、あるいは最善の利益の配分を実現するからである。

批判

福利のために権利が浅薄なものになる。(暴動を避けるために無実のひとを犠牲にしてよいか?)

最善の利益の配分をどうすればよいか、について、また個人の利益がなにかについて、合意がない。

3)契約説

権利が尊重されるのは、ある条件(ーーー無知のベール、誰も理不尽には拒絶しないであろうーー)のもと、自分たちが合意した権利関係の原則が決まるからである。

権利に対する批判

権利はバラバラで地域社会から孤立した人間観を前提としており、あまりにも個人主義的で、また、エゴイズムを増長させている。もっとも、集団の権利なども認められており、個人主義的とは言えない、という論者もいる。

ただ、権利が強調される言説が支配的になり、権利の保持者に焦点があつまりすぎて、個人の責任が軽視されがちになる、という論者もいる。

(*)

Wesley Hofeld,

Legal Rights

PDF] 1 Rights and What We Owe to Each Other

なお、

自由・義務・権利の論理関係参照

Rights stanford.edu

これがよくまとまっているやないけ、と思ってメモ風にまとめた。

定義

Rights are entitlements (not) to perform certain actions, or (not) to be in certain states; or entitlements that others (not) perform certain actions or (not) be in certain states.

権利とは、自分が何らかの行為をする、あるいは、何らかの状態にある資格であり、また、他人に何らかの状態をさせ、あるいは、何らかの状態にする資格である。

構造・要素

権利には自由・請求権などの要素からなる内部構造がある。

一次的規則ー何かをし、あるいは何かをしないようにする規則

自由権

A has a privilege to φ if and only if A has no duty not to φ.

Aは φ する自由権を有する⇔ Aは φ をしない義務がない

請求権

A has a claim that B φ if and only if B has a duty to A to φ

AはBが φ する請求権を有する⇔BはAにφする義務がある。

二次的規則 一次的規則を発生・変更・移転・消滅させる規則

権限

A has a power if and only if A has the ability within a set of rules to alter her own or another's Hohfeldian incidents.

Aは権限がある ⇔Aは規則の範囲内で自分あるいは他人の法律関係を変更する能力がある。

例

船長は船員にデッキの掃除を命令する権限を行使することによって 船員にある義務を発生させ、ある自由を消滅させる

諾約者はある約束をする権限を行使することで、受約者にあることをする義務を発生させる。

家主はお隣さんを招待する権限を行使することで、彼が家に入らない義務を放棄する。

司令官は船長の権限を剥奪する権限がある。

免責権

B has an immunity if and only if A lacks the ability within a set of rules to alter B's Hohfeldian incidents.

Bは免責権がある。⇔AにはBの要素を変更する能力がない。

例

議会は国民が十字架の前に跪かせる能力がない。⇔国民は(跪かない)免責権がある。

自由権・請求権・権限・免責権などの原子的要素は単独で、権利になりうるが、ある構造をなして、分子的権利を構成することもある。

例 所有権

Aはコンピューターの所有権がある。

⇔

一次的権利

Aはコンピューターを使う自由権があり、使わない義務はない。

Aは他人がコンピューターを使わせない請求権があり、他人は使わない義務がある。

二次的権利

Aは他人がこのコンピューターを使わせない請求権を放棄して、義務を解除する権限があり、所有権に対する請求権を放棄し、あるいは、移転する権限がある。また、

他人がAのこのコンピューターの所有権に関する請求権を消滅・移転させない、免責権がある。

自由権・権限は権利の保持者が何かをする能動的権利であり、請求権・免責権は他人に何をしてもらう受動的権利である。

他人から介入されない資格は否定的権利、また、何らかの財やサービスを受ける資格は肯定的権利である。

機能ーー権利の保持者に対して何をするか

意志説

More specifically, a will theorist asserts that the function of a right is to give its holder control over another's duty. Your property right diagrammed in the figure above is a right because it contains a power to waive (or annul, or transfer) others' duties. You are the “sovereign” of your computer, in that you may permit others to touch it or not at your discretion.

権利の保持者は権利によって、他人の義務について支配権を与えられる。コンピューターの所有権をもっている人は、他人の義務を消滅・移転などさせる権限をもっている。いわば、コンピュータの”統治者”であり、自分の裁量で、他人がそのコンピューターに触ることを許可することができる。受約者は、諾約者の義務を解除することができる。要するに、他人がある仕方で行動する義務を支配する能力が授与されているのである。

批判

奴隷にならないことなど、放棄できない権利もある。

幼児や動物などの権利を説明できない。

利益説

Interest theorists maintain that the function of a right is to further the right-holder's interests. An owner has a right, according to the interest theory, not because owners have choices, but because the ownership makes owners better off. A promisee has a right because promisees have some interest in the performance of the promise, or (alternatively) some interest in being able to form voluntary bonds with others. Rights, the interest theorist says, are the Hohfeldian incidents you have that are good for you.

権利の保持者は、権利によってその利益が促進されるのである。所有者が選択肢を持っているからではなく、所有権によって所有者の利益が高まるのである。受約者は諾約者が約束を守ることによって利益がある。

批判

利益関係はあっても権利がない場合もある。例 宝くじにあたった配偶者の賞金を支払ってもらう利益

ある裁判官が被告人に死刑を宣告するどんな利益があってもだからといって、その権限が正当化されるわけではなく、権限とは無関係

権利と理由

切り札としての権利

The reasons that rights provide are particularly powerful or weighty reasons, which override reasons of other sorts. Dworkin's metaphor is of rights as “trumps.” (Dworkin 1984) Rights give reasons to treat their holders in certain ways or permit their holders to act in certain ways, even if some social aim would be served by doing otherwise

権利を持っているということは、ある社会政策をくつがえす切り札として規範的強制力があり、権利を支える理由は、他の理由よりも強力である。

もっとも、

Dworkin's metaphor suggests that rights trump non-right objectives, such as increasing national wealth. What of the priority of one right with respect to another? We can keep to the trumps metaphor while recognizing that some rights have a higher priority than others. Within the trump suit, a jack still beats a seven or a three. Your right of way at a flashing yellow light has priority over the right of way of the driver facing a flashing red; and the right of way of an ambulance with sirens on trumps you both.

権利同士では、 トランプの切り札ジャック(11)は7や3を負かすように、例えば、信号での黄色が点灯している場合、歩行者の歩行する権利の方が、赤信号に直面している自動車が運行する権利より優先する。もっとも、両者の権利は救急車が走行する権利には及ばない、というように権利同士では優先関係がある。

とすれば、なによりも最優先される絶対的権利があるか、という疑問がわくが、例えば、殺害されない権利を絶対的な例として論者もいる。もっとも、100万人を救うためには1人の犠牲は致し方ないのではないか、その意味ではそうした権利も絶対的とはいえないのではないか、という論者もいる。

ある権利が他の権利に優先する場合があるとすれば、衝突する場合もあるようにも思える。例えば、人々がデモする権利は政府の公共の秩序を守る権利と衝突するようにも思える。

これに対して、例えば、デモする権利というのは、実際には、他人の生命財産を侵害しない、致死病を蔓延させない など の場合に行使できる権利であり、政府の公共の場所に対する権限も、平和的デモを阻害しないで、致死病の蔓延につながらない など の場合に限り行使できる権利である、といった具合に条件を特定すればジグゾーパズルが断片同士がぶつかりあわずうまく組みあうように権利同士も衝突することはないのだ、という論者もいる。これに対して、「など」というのがくせ者で、そもそもすべての条件を列挙して特定化することはできない、と反論するものもいる。

権利は衝突する場合だけでなく、ある権利が他の権利を支える場合もある。

Nickel (2008) develops a typology of supporting relations between rights. One right strongly supports another when it is logically or practically inconsistent to endorse the implementation of second right without endorsing the simultaneous implementation of the first. For example, the right to bodily security strongly supports the right to freedom of assembly. One right weakly supports another when it is useful but not essential to it. The right to education, for example, weakly supports the right to a fair trial. Nickel argues that the strength of supporting relations between rights varies with quality of implementation. Poorly implemented rights provide little support to other rights, while ones that are more effectively implemented tend to provide greater support to other rights. The right to due process supports the right to equal treatment for members of different racial and ethnic groups―but the support will be soft if the right to due process is only weakly implemented.

一方の権利を認めて他方の権利を認めないと実際的、論理的に不整合になる場合、他方は一方を強く支え、他方が一方の権利に本質的と言えないまでも有益な場合には、弱い支えになっている。例えば、身体上の安全が確保される権利は集会の自由を強く支え、教育を受ける権利は、公正な裁判を受ける権利の弱い支えになっている。また、同じ権利でもそれが強化されれば、他の権利の強い支えになるが、いい加減だと弱い支えにしかならない。適正手続の権利は、平等に扱われる権利の支えているが、しかし、適正手続きの権利がいい加減に施行されていると、支えは軟弱なものにならざるえない。

権利の正当化

1)地位説

ある地位・属性を有するからその権利は尊重される。

批判

地位の根拠が宗教的、形而上学的で不確かである。

不可侵の権利についてどれがそれか、合意がない。

2)手段説

権利が尊重されるのは、それが全体の福利、あるいは最善の利益の配分を実現するからである。

批判

福利のために権利が浅薄なものになる。(暴動を避けるために無実のひとを犠牲にしてよいか?)

最善の利益の配分をどうすればよいか、について、また個人の利益がなにかについて、合意がない。

3)契約説

権利が尊重されるのは、ある条件(ーーー無知のベール、誰も理不尽には拒絶しないであろうーー)のもと、自分たちが合意した権利関係の原則が決まるからである。

権利に対する批判

権利はバラバラで地域社会から孤立した人間観を前提としており、あまりにも個人主義的で、また、エゴイズムを増長させている。もっとも、集団の権利なども認められており、個人主義的とは言えない、という論者もいる。

ただ、権利が強調される言説が支配的になり、権利の保持者に焦点があつまりすぎて、個人の責任が軽視されがちになる、という論者もいる。

(*)

Wesley Hofeld,

Legal Rights

PDF] 1 Rights and What We Owe to Each Other

なお、

自由・義務・権利の論理関係参照