MONDAY, SEP 8, 2014 12:30 AM +0900

We still lie about slavery: Here’s the truth about how the American economy and power were built on forced migration and torture

All these decades later, our history books are filled with myths and mistruths. It is time for a true reckoning

EDWARD E. BAPTIST

奴隷制度によってアメリカは経済的に強大な国家になったにもかかわらず、奴隷の自由のために南北戦争があったが、アメリカが強大な国になったことについても、また、奴隷の解放についても、黒人はたいした役割は果たさなかったかのようにしか語られない、と。

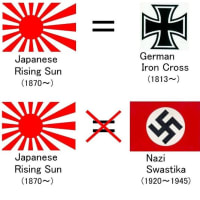

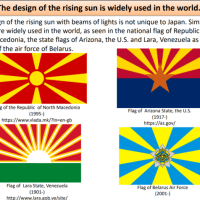

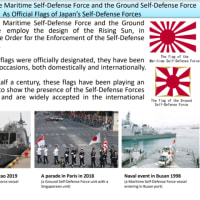

性奴隷問題についても同じですね、

Thanks to U.S. journalists such as Fackler(NYT), Americans know only sanitized version of the past.

(歴史問題)

We still lie about slavery: Here’s the truth about how the American economy and power were built on forced migration and torture

All these decades later, our history books are filled with myths and mistruths. It is time for a true reckoning

EDWARD E. BAPTIST

By the 1930s, most white Americans had been demanding for decades that they hear only a sanitized version of the past into which Lorenzo Ivy had been born.

So although anti- and proslavery conclusions about slavery’s morality were different, their premises about slavery-as- a-business model matched. Both agreed that slavery was inherently unprofitable. It was an old, static system that belonged to an earlier time. Slave labor was inefficient to begin with, slave productivity did not increase to keep pace with industrialization, and enslavers did not act like modern profit- seeking businessmen. As a system, slavery had never adapted or changed to thrive in the new industrial economy—let alone to play a premier role as a driver of economic expansion—and had been little more than a drag on the explosive growth that had built the modern United States. In fact, during the Civil War, northerners were so convinced of these points that they believed that shifting from slave labor to free labor would dramatically increase cotton productivity.

It didn’t. But even though the data of declining productivity over the ensuing three score and ten years suggested that slavery might have been the most efficient way to produce the world’s most important crop, no one let empirical tests change their minds.

Instead, historians of Woodrow Wilson’s generation imprinted the stamp of academic research on the idea that slavery was separate from the great economic and social transformations of the Western world during the nineteenth century

The way that Americans remember slavery has changed dramatically since then. In tandem with widespread desegregation of public spaces and the assertion of black cultural power in the years between World War II and the 1990s came a new understanding of the experience of slavery. No longer did academic historians describe slavery as a school in which patient masters and mistresses trained irresponsible savages for futures of perpetual servitude. Slavery’s denial of rights now prefigured Jim Crow, while enslaved people’s resistance predicted the collective self-assertion that developed into first the civil rights movement and later, Black Power.

But perhaps the changes were not so great as they seemed on the surface. The focus on showing African Americans as assertive rebels, for instance, implied an uncomfortable corollary. If one should be impressed by those who rebelled, because they resisted, one should not be proud of those who did not. And there were very few rebellions in the history of slavery in the United States.

The first major assumption is that, as an economic system—a way of producing and trading commodities—American slavery was fundamentally different from the rest of the modern economy and separate from it. Stories about industrialization emphasize white immigrants and clever inventors, but they leave out cotton fields and slave labor. This perspective implies not only that slavery didn’t change, but that slavery and enslaved African Americans had little long-term influence on the rise of the United States during the nineteenth century, a period in which the nation went from being a minor European trading partner to becoming the world’s largest economy—one of the central stories of American history.

And once the violence of slavery was minimized, another voice could whisper, saying that African Americans, both before and after emancipation, were denied the rights of citizens because they would not fight for them.

All these assumptions lead to still more implications, ones that shape attitudes, identities, and debates about policy. If slavery was outside of US history, for instance—if indeed it was a drag and not a rocket booster to American economic growth—then slavery was not implicated in US growth, success, power, and wealth

Did Ivy know if any slaves had been sold here? Now, perhaps, the room grew darker.

For more than a century, white people in the United States had been singling out slave traders as an exception: unscrupulous lower-class outsiders who pried apart paternalist bonds.

But Ivy spilled out a rush of very different words. “They sold slaves here and everywhere. I’ve seen droves of Negroes brought in here on foot going South to be sold. Each one of them had an old tow sack on his back with everything he’s got in it. Over the hills they came in lines reaching as far as the eye can see. They walked in double lines chained together by twos. They walk ‘em here to the railroad and shipped ’em south like cattle.”

Then Lorenzo Ivy said this: “Truly, son, the half has never been told.”

The returns from cotton monopoly powered the modernization of the rest of the American economy, and by the time of the Civil War, the United States had become the second nation to undergo large-scale industrialization. In fact, slavery’s expansion shaped every crucial aspect of the economy and politics of the new nation—not only increasing its power and size, but also, eventually, dividing US politics, differentiating regional identities and interests, and helping to make civil war possible.

The idea that the commodification and suffering and forced labor of African Americans is what made the United States powerful and rich is not an idea that people necessarily are happy to hear

奴隷制度によってアメリカは経済的に強大な国家になったにもかかわらず、奴隷の自由のために南北戦争があったが、アメリカが強大な国になったことについても、また、奴隷の解放についても、黒人はたいした役割は果たさなかったかのようにしか語られない、と。

性奴隷問題についても同じですね、

Thanks to U.S. journalists such as Fackler(NYT), Americans know only sanitized version of the past.

(歴史問題)