NEWS & POLITICS

It's Not All About Democracy: The Very Dark Side of American History

This tradition goes back to the treatment of Native Americans in the 19th century.

By Robert Parry, Peter Dale Scott / Consortium News January 6, 2015

一般人を虐殺し、インフラまで粉砕するテロ作戦、かつ、総力戦は、アメリカインディアン虐殺した当初からの、アメリカの軍事戦術の伝統である、と。

敵は、暴力や残忍な力によってしか、わからない、野蛮人であり、もし、殺戮していなければ、もっとひどいことになっていただろう、という発想は、ずっと続いているような気もしますね。

目的は手段を正当化する、というのが一概間違いとは言いませんが、例えば、目的を達成するために必要最小限の手段であったか、もし、それをしていなかったら本当にそんな酷い事態になっていたかなどは問われてよい。

例えばの話、日本もアジアで残忍な殺戮を繰り返し、それを制止する必要があったとしても、あの時点で、原爆を落とす必要があったか、原爆を落とさなければ、アメリカやアジアはもっとひどいことになっていたか、というと、そんなことはまるでないわけで、日本人に対する差別意識および、皆殺しの総力戦の発想での戦争だったわけです。

これは、別に、アメリカだけの問題ではなく、日本も、無差別空襲したり、捕虜虐待したり、人体実験したり、非道の限りを尽くしたわけですけど、アメリカは単に勝利したために無罪放免、戦後も同じ過ちを繰り返し、NYTのファクラー記者と、APの山口記者らが、協力して、米軍の罪について、一般のアメリカ人には知られないようになっていて、一般人は、アメリカは正義の戦争をしている、と思っている人もかなり多い。

勝てばなんでも赦される、というイデオロギーは何とかしてほしい、と思うのであります。

It's Not All About Democracy: The Very Dark Side of American History

This tradition goes back to the treatment of Native Americans in the 19th century.

By Robert Parry, Peter Dale Scott / Consortium News January 6, 2015

The American people are largely oblivious to this hidden tradition because most of the literature advocating state-sponsored terror is carefully confined to national security circles and rarely spills out into the public debate, which is instead dominated by feel-good messages about well-intentioned U.S. interventions abroad.

Yet the historical record shows that terror tactics have long been a dark side of U.S. military doctrine.

Some historians trace the formal acceptance of those brutal tenets to the 1860s when the U.S. Army was facing challenge from a rebellious South and resistance from Native Americans in the West. Out of those crises emerged the modern military concept of "total war" -- which considers attacks on civilians and their economic infrastructure an integral part of a victorious strategy.

"They were scalped; their brains knocked out; the men used their knives, ripped open women, clubbed little children, knocked them in the head with their guns, beat their brains out, mutilated their bodies in every sense of the word." [U.S. Cong., Senate, 39 Cong., 2nd Sess., "The Chivington Massacre," Reports of the Committees.]

NEWS & POLITICS

It's Not All About Democracy: The Very Dark Side of American History

This tradition goes back to the treatment of Native Americans in the 19th century.

By Robert Parry, Peter Dale Scott / Consortium News January 6, 2015

4 COMMENTS

Editor's Note: Many Americans view their country and its soldiers as the "good guys" spreading "democracy" and "liberty" around the world. When the United States inflicts unnecessary death and destruction, it's viewed as a mistake or an aberration.

In the following article, Peter Dale Scott and Robert Parry examine the long history of these acts of brutality, a record that suggests they are neither a "mistake" nor an "aberration" but rather conscious counterinsurgency doctrine on the "dark side."

There is a dark -- seldom acknowledged -- thread that runs through U.S. military doctrine, dating back to the early days of the Republic.

This military tradition has explicitly defended the selective use of terror, whether in suppressing Native American resistance on the frontiers in the 19th Century or in protecting U.S. interests abroad in the 20th Century or fighting the "war on terror" over the last decade.

The American people are largely oblivious to this hidden tradition because most of the literature advocating state-sponsored terror is carefully confined to national security circles and rarely spills out into the public debate, which is instead dominated by feel-good messages about well-intentioned U.S. interventions abroad.

Over the decades, congressional and journalistic investigations have exposed some of these abuses. The recent release of the Senate torture report is one example. But when that does happen, the cases are usually deemed anomalies or excesses by out-of-control soldiers.

Yet the historical record shows that terror tactics have long been a dark side of U.S. military doctrine. The theories survive today in textbooks on counterinsurgency warfare, "low-intensity" conflict and "counter-terrorism."

Some historians trace the formal acceptance of those brutal tenets to the 1860s when the U.S. Army was facing challenge from a rebellious South and resistance from Native Americans in the West. Out of those crises emerged the modern military concept of "total war" -- which considers attacks on civilians and their economic infrastructure an integral part of a victorious strategy.

In 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman cut a swath of destruction through civilian territory in Georgia and the Carolinas. His plan was to destroy the South's will to fight and its ability to sustain a large army in the field. The devastation left plantations in flames and brought widespread Confederate complaints of rape and murder of civilians.

Meanwhile, in Colorado, Colonel John M. Chivington and the Third Colorado Cavalry were employing their own terror tactics to pacify Cheyennes. A scout named John Smith later described the attack at Sand Creek, Colorado, on unsuspecting Indians at a peaceful encampment:

"They were scalped; their brains knocked out; the men used their knives, ripped open women, clubbed little children, knocked them in the head with their guns, beat their brains out, mutilated their bodies in every sense of the word." [U.S. Cong., Senate, 39 Cong., 2nd Sess., "The Chivington Massacre," Reports of the Committees.]

Though Smith's objectivity was challenged at the time, today even defenders of the Sand Creek raid concede that most women and children there were killed and mutilated. [See Lt. Col. William R. Dunn, I Stand by Sand Creek.]

Yet, in the 1860s, many whites in Colorado saw the slaughter as the only realistic way to bring peace, just as Sherman viewed his "march to the sea" as necessary to force the South's surrender.

The brutal tactics in the West also helped clear the way for the transcontinental railroad, built fortunes for favored businessmen and consolidated Republican political power for more than six decades, until the Great Depression of the 1930s. [See Consortiumnews.com's "Indian Genocide and Republican Power."]

Four years after the Civil War, Sherman became commanding general of the Army and incorporated the Indian pacification strategies -- as well as his own tactics -- into U.S. military doctrine. General Philip H. Sheridan, who had led Indian wars in the Missouri territory, succeeded Sherman in 1883 and further entrenched those strategies as policy. [See Ward Churchill, A Little Matter of Genocide.]

By the end of the 19th Century, the Native American warriors had been vanquished, but the Army's winning strategies lived on.

Imperial America

When the United States claimed the Philippines as a prize in the Spanish-American War, Filipino insurgents resisted. In 1900, the U.S. commander, General J. Franklin Bell, consciously modeled his brutal counterinsurgency campaign after the Indian wars and Sherman's "march to the sea."

Bell believed that by punishing the wealthier Filipinos through destruction of their homes -- much as Sherman had done in the South -- they would be coerced into helping convince their countrymen to submit.

Learning from the Indian wars, he also isolated the guerrillas by forcing Filipinos into tightly controlled zones where schools were built and other social amenities were provided.

"The entire population outside of the major cities in Batangas was herded into concentration camps," wrote historian Stuart Creighton Miller. "Bell's main target was the wealthier and better-educated classes. … Adding insult to injury, Bell made these people carry the petrol used to burn their own country homes." [See Miller's "Benevolent Assimilation."]

For those outside the protected areas, there was terror. A supportive news correspondent described one scene in which American soldiers killed "men, women, children … from lads of 10 and up, an idea prevailing that the Filipino, as such, was little better than a dog. …

"Our soldiers have pumped salt water into men to 'make them talk,' have taken prisoner people who held up their hands and peacefully surrendered, and an hour later, without an atom of evidence to show they were even insurrectos, stood them on a bridge and shot them down one by one, to drop into the water below and float down as an example to those who found their bullet-riddled corpses.

Defending the tactics, the correspondent noted that "it is not civilized warfare, but we are not dealing with a civilized people. The only thing they know and fear is force, violence, and brutality." [Philadelphia Ledger, Nov. 19, 1900]

While psy-war included propaganda and disinformation, it also relied on terror tactics of a demonstrative nature. An Army psy-war pamphlet, drawing on Lansdale's experience in the Philippines, advocated "exemplary criminal violence -- the murder and mutilation of captives and the display of their bodies," according to Michael McClintock's Instruments of Statecraft.

On to Vietnam

"I recall a phrase we used in the field, MAM, for military-age male," Powell wrote in his much-lauded memoir, My American Journey. "If a helo [a U.S. helicopter] spotted a peasant in black pajamas who looked remotely suspicious, a possible MAM, the pilot would circle and fire in front of him. If he moved, his movement was judged evidence of hostile intent, and the next burst was not in front, but at him.

The secret U.S.-Indonesian military connections paid off for Washington when a political crisis erupted, threatening Sukarno's government.

To counter Indonesia's powerful Communist Party, known as the PKI, the army's Red Berets organized the slaughter of tens of thousands of men, women and children. So many bodies were dumped into the rivers of East Java that they ran red with blood.

U.S. Media Sympathy

Elite U.S. reaction to the horrific slaughter was muted and has remained ambivalent ever since. The Johnson administration denied any responsibility for the massacres, but New York Times columnist James Reston spoke for many opinion leaders when he approvingly termed the bloody developments in Indonesia "a gleam of light in Asia."

The American denials of involvement held until 1990 when U.S. diplomats admitted to a reporter that they had aided the Indonesian army by supplying lists of suspected communists.

Kadane's story provoked a telling response from Washington Post senior editorial writer Stephen S. Rosenfeld. He accepted the fact that American officials had assisted "this fearsome slaughter," but then justified the killings.

"Though the means were grievously tainted, we -- the fastidious among us as well as the hard-headed and cynical -- can be said to have enjoyed the fruits in the geopolitical stability of that important part of Asia, in the revolution that never happened." [Washington Post, July 13, 1990]

The fruit tasted far more bitter to the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago, however. In 1975, the army of Indonesia's new dictator, Gen. Suharto, invaded the former Portuguese colony of East Timor. When the East Timorese resisted, the Indonesian army returned to its gruesome bag of tricks, engaging in virtual genocide against the population.

A Catholic missionary provided an eyewitness account of one search-and-destroy mission in East Timor in 1981.

"We saw with our own eyes the massacre of the people who were surrendering: all dead, even women and children, even the littlest ones. … Not even pregnant women were spared: they were cut open. …. They did what they had done to small children the previous year, grabbing them by the legs and smashing their heads against rocks. …

Public Revulsion

Through television in the 1960-70s, the Vietnam War finally brought the horrors of counterinsurgency home to millions of Americans. They watched as U.S. troops torched villages and forced distraught old women to leave ancestral homes.

Camera crews caught on film brutal interrogation of Viet Cong suspects, the execution of one young VC officer, and the bombing of children with napalm.

In effect, the Vietnam War was the first time Americans got to witness the pacification strategies that had evolved secretly as national security policy since the 19th Century. As a result, millions of Americans protested the war's conduct and Congress belatedly compelled an end to U.S. participation in 1974

Reagan also added an important new component to the mix. Recognizing how graphic images and honest reporting from the war zone had undercut public support for the counterinsurgency in Vietnam, Reagan authorized an aggressive domestic "public diplomacy" operation which practiced what was called "perception management" -- in effect, intimidating journalists to ensure that only sanitized information would reach the American people.

What is clear from these experiences in Indonesia, Vietnam, Central America and elsewhere is that the United States, for generations, has sustained two parallel but opposed states of mind about military atrocities and human rights: one of U.S. benevolence, generally held by the public, and the other of ends-justify-the-means brutality embraced by counterinsurgency specialists.

(歴史問題)

一般人を虐殺し、インフラまで粉砕するテロ作戦、かつ、総力戦は、アメリカインディアン虐殺した当初からの、アメリカの軍事戦術の伝統である、と。

敵は、暴力や残忍な力によってしか、わからない、野蛮人であり、もし、殺戮していなければ、もっとひどいことになっていただろう、という発想は、ずっと続いているような気もしますね。

目的は手段を正当化する、というのが一概間違いとは言いませんが、例えば、目的を達成するために必要最小限の手段であったか、もし、それをしていなかったら本当にそんな酷い事態になっていたかなどは問われてよい。

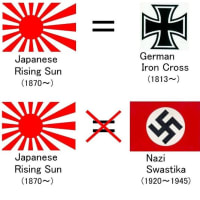

例えばの話、日本もアジアで残忍な殺戮を繰り返し、それを制止する必要があったとしても、あの時点で、原爆を落とす必要があったか、原爆を落とさなければ、アメリカやアジアはもっとひどいことになっていたか、というと、そんなことはまるでないわけで、日本人に対する差別意識および、皆殺しの総力戦の発想での戦争だったわけです。

これは、別に、アメリカだけの問題ではなく、日本も、無差別空襲したり、捕虜虐待したり、人体実験したり、非道の限りを尽くしたわけですけど、アメリカは単に勝利したために無罪放免、戦後も同じ過ちを繰り返し、NYTのファクラー記者と、APの山口記者らが、協力して、米軍の罪について、一般のアメリカ人には知られないようになっていて、一般人は、アメリカは正義の戦争をしている、と思っている人もかなり多い。

勝てばなんでも赦される、というイデオロギーは何とかしてほしい、と思うのであります。