Bull Market Blues

(ブル・マーケット・ブルース)

Paul Krugman

NYT:JULY 15, 2016

(ブル・マーケット・ブルース)

Paul Krugman

NYT:JULY 15, 2016

Like most economists, I don't usually have much to say about stocks. Stocks are even more susceptible than other markets to popular delusions and the madness of crowds, and stock prices generally have a lot less to do with the state of the economy or its future prospects than many people believe. As the economist Paul Samuelson put it, "Wall Street indexes predicted nine out of the last five recessions."

殆どのエコノミストと同じように、僕は普段、株について余り言うことがありません。

株は世間の思い込みだの群衆のキチガイ沙汰に対して、他のマーケットよりも更に影響を受け易いものであり、株価と経済状態や今後の見通しとの関係性は通常、多くの人が考えているよりも遥かに低いのです。

エコノミストのポール・サミュエルソンが言ったように、「ウォール街の指数は過去5回の不況のうち9回予測した」わけですから。

Still, we shouldn't completely ignore stock prices. The fact that the major averages have lately been hitting new highs — the Dow has risen 177 percent from its low point in March 2009 — is newsworthy and noteworthy. What are those Wall Street indexes telling us?

とはいえ、株価を完全に無視するべきではありません。

主要な平均指数が最近新高値を付けているという事実(ダウジョーンズは2009年3月の安値比+177%)は、ニュースにも注意にも値するものです。

さて、それらのウォール街の指数は僕らに何を語っているのか?

The answer, I'd suggest, isn't entirely positive. In fact, in some ways the stock market's gains reflect economic weaknesses, not strengths. And understanding how that works may help us make sense of the troubling state our economy is in.

その答えは、そうですね、完全にポジティブではないと申し上げましょう。

実は、株価の上昇は或る意味、経済の強さではなく弱さを反映します。

そしてそれがどのように動くのかを理解することは、僕らの経済が困った状態になっていることを理解する助けになるかもしれません。

O.K., let's start with the myth Samuelson was debunking, the claim that stock prices are the measure of the economy as a whole. That myth used to be popular on the political right, with prominent conservative economists publishing articles with titles like "Obama's Radicalism Is Killing the Dow."

ってことで、サミュエルソンが暴いた神話、株価は経済全体の評価基準だという主張から始めましょう。

その神話はかつて、政治的右派に人気があり、著名な保守派エコノミストによる『オバマの改革主義がダウを殺す』なんてタイトルを付けた記事が発表されていました。

Strange to say, however, we began hearing that line a lot less once stock prices turned around and began their huge surge — which started just six weeks after President Obama was inaugurated. (But polling suggests that a majority of self-identified Republicans still haven't noticed that surge, and believe that stocks have gone down in the Obama era.)

でも奇妙かもしれませんが、株価が好転して急上昇を始めた途端に、オバマ大統領の就任後たった6週間で、そんな論調が全然聞こえなくなってきました。

(でも世論調査からは、自称共和党員の大半は今もその急上昇に気付いておらず、オバマ時代に株は下がったと信じていることがわかります。)

The truth, in any case, is that there are three big points of slippage between stock prices and the success of the economy in general. First, stock prices reflect profits, not overall incomes. Second, they also reflect the availability of other investment opportunities — or the lack thereof. Finally, the relationship between stock prices and real investment that expands the economy's capacity has gotten very tenuous.

いずれにせよ、株価と全体的な経済の成功の間には、大きなズレのポイントが3つあるというのが真実です。

一つ目は、株価は全体的な所得ではなく利益を反映しているということ。

二つ目は、株価は他の投資機会の存在または欠落も反映しているということ。

最後に、株価と経済のキャパを拡大する実物投資の関係は非常に乏しくなってしまったということ。

On the first point: We measure the economy's success by the extent to which it generates rising incomes for the population. But stocks don't reflect incomes in general; they only reflect the part of income that shows up as profits.

一つ目についてですが、僕らは人々の所得をどのくらい増やしているかで、経済の成功度合いを測ります。

でも株は一般的な所得を反映しておらず、利益となる所得の一部分のみを反映しています。

This wouldn't matter if the share of profits in overall income were stable; but it isn't. The share of profits in national income fluctuates, but it has been a lot higher in recent years than it was during the great stock surge of the late 1990s — that is, we've had a profits boom without a comparably large economic boom, making the relationship between profits and prosperity weak at best. We are not, in fact, partying like it's 1999.

所得全体における利益の割合が一定ならかまわないのですが、そうではありません。

国民所得における利益の割合は変動しますが、近年は1990年代終盤の大株価高の間をも遥かに上回るまでに高くなっています…それはつまり、同程度の大きな好況なくして利益増大があり、利益と豊かさの関係を良く言って弱いものにしたということです。

実際、僕らは1999年のように浮かれていません。

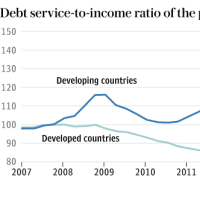

On the second point: When investors buy stocks, they're buying a share of future profits. What that's worth to them depends on what other options they have for converting money today into income tomorrow. And these days those options are pretty poor, with interest rates on long-term government bonds not only very low by historical standards but zero or negative once you adjust for inflation. So investors are willing to pay a lot for future income, hence high stock prices for any given level of profits.

二つ目について。

投資家が株を買う時、彼らは将来の利益の一部を買っているのです。

彼らにとっての価値は、今日あるお金を明日の収益に換える以外の選択肢次第です。

また、この頃は、そのような選択肢が非常に乏しく、政府の長期債の金利など歴史的水準を大きく下回っているだけでなく、インフレ調整後はマイナスになってしまいます。

ですから投資家は将来の収益に大金を喜んで支払うのであり、従ってどの利益の水準に対しても株価が割高になるというわけです。

But why are long-term interest rates so low? As I argued in my last column, the answer is basically weakness in investment spending, despite low short-term interest rates, which suggests that those rates will have to stay low for a long time.

とはいえ、何故長期金利がこれほど低いのでしょう?

前回のコラムで書いた通り、その答えは基本的に、低い短期金利にも拘らずの投資支出低迷にあり、それらの金利は長期に亘って低い水準であり続けなければならないことを示唆しています。

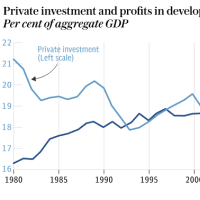

This may seem, however, to present a paradox. If the private sector doesn't see itself as having a lot of good investment opportunities, how can profits be so high? The answer, I'd suggest, is that these days profits often seem to bear little relationship to investment in new capacity. Instead, profits come from some kind of market power — brand position, the advantages of an established network, or good old-fashioned monopoly. And companies making profits from such power can simultaneously have high stock prices and little reason to spend.

しかしそれは矛盾を提示しているように見受けられるかもしれません。

民間部門が自分達に優良な投資案件が沢山あると思っていないのならば、どうして利益をあれほど沢山出せるのでしょう?

昨今の利益は新しい生産能力に対する投資と殆ど関係性がないように見受けられることが多い、と言うのが答えだと思います。

その代わりに、利益は何らかの市場の力から来るものであり、それはブランド・ポジションや、確立されたネットワークのアドバンテージや、昔ながらの独占です。

それに、そのような力から利益を出している企業は、高い株価を保ちながら支出する理由を殆ど持たずにいられるのです。

Consider the fact that the three most valuable companies in America are Apple, Google and Microsoft. None of the three spends large sums on bricks and mortar. In fact, all three are sitting on huge reserves of cash. When interest rates go down, they don't have much incentive to spend more on expanding their businesses; they just keep raking in earnings, and the public becomes willing to pay more for a piece of those earnings.

米国で最も時価総額の高い企業はアップル、グーグル、マイクロソフトだという事実を考えてみてください。

3社のいずれも煉瓦やモルタルに巨額を注ぎ込んでいません。

実は、3社とも莫大な手元資金を抱えています。

金利が下がっても、これらの企業には事業拡大に支出を増やすインセンティブも余りありません。

収益番付をキープするだけであり、世間もそのような収益のおこぼれをもらうために、喜んでもっと金を出すようになります。

In other words, while record stock prices do put the lie to claims that the Obama administration has been anti-business, they're not evidence of a healthy economy. If anything, they're a sign of an economy with too few opportunities for productive investment and too much monopoly power.

要するに、記録的な株価はオバマ政権はアンチ・ビジネスだという主張が嘘だと暴いてくれますが、経済が健全であるという証拠ではありません。

あるとすれば、それは生産的投資の機会が余りに乏しく、独占力が余りに強い経済のサインです。

So when you read headlines about stock prices, remember: What's good for the Dow isn't necessarily good for America, or vice versa.

ですから、株価に関する見出しを目にしたら、これを思い出してください。

ダウにとって良いことが必ずしも米国にとって良いことではなく、その逆もまたしかりだと。