Bernadette Roberts (バーナデット・ロバーツ) 1931~ (02)

前の内容:

Bernadette Roberts (バーナデット・ロバーツ) 1931~ (01)

2013-06-10 00:54:26 | 話題 (opinion)

Self

An Outline (Part One)

This is a complex chapter in which layers of insight blend and

(con)fuse, only to find an attempt at separation in her next book: 'What

is Self?'. Of course, that separation is attained by further layers of

insight, but at least that way there's bound to be something for

everyone.

By way of outline, I'll attempt to do some separation for the reader

here, but expect to sense what I sense: that blending of layers of

insight. Help from fellow Roberts watchers is openly sought! Here

goes...

In discussing self, Roberts makes clear that her knowledge of self comes

from the perspective of no-self. Traditionally, self is known by

not-self, which may otherwise be known as the personal unconscious or

the collective unconscious.

She recognizes that her view of self is so different from that of the

traditional view, that it may appear "incomprehensible and

unacceptable."

The true object of consciousness, Roberts says, is consciousness. This

is the knowing-self.

The other dimension composing the whole of consciousness is the

feeling-self, in which the object of consciousness is the senses.

Roberts compares the nature of consciousness and the nature of the

sensory system. The nature of consciousness is that of the self which

arises from the reflexive action of the mind, or the action of the mind

attending to itself. Out of this action the self arises, or thinker,

doer, feeler arises. This is the knowing-self, consciousness attending

to consciousness.

The sensory system looks not inward at itself, but outward to its

environment, for which is stands ready to respond.

The problem here, Roberts declares, is that we may fail to distinguish

between the self and sensory objects in the environment. This occurs

because the sensory objects are not seen as they are; they are seen as

filtered through the mind, and, therefore, as receivers of a stamp of

subjectivity.

This problem exists as long as the self exists, as long as the mind

bends on itself or attends to itself, as long as thinker, feeler, doer,

stand together as self.

The difference between consciousness and the senses becomes clear once

the self is no more, once the mind ceases to bend on itself.

Such was Roberts' experience. When the self disappeared into a void;

when the mind could no longer attend to itself, or look within, the

senses took over without falling into the same void as consciousness.

However, it was not only the self that had disappeared, but God too: the

union forming the Divine Awareness aspect of consciousness had

disappeared. Now it felt as though all life energy had been depleted.

This sense of life, she says, constitutes the feeling-self, which is

subtle energy located at the center of consciousness or center of being,

and whose existence depends upon the knowing-self, even as a planet

depends upon gravitational force for its placement.

It is these two divisions, the knowing self and feeling self, which form

the whole of consciousness.

With the disappearance of self and God, the entire affective system of

feeling and emotion disappeared, for it could not be kept in place any

longer.

This disappearance of the affective system, and the recognition that it

could not be resurrected, was the basis for Roberts' feelings of terror.

Once confronted, however, the terror went away and never reappeared.

And Roberts then discovered that the stillness of no-self was not

effected or moved by any terror or element of the unknown at all. She

learned, too, that the mind is ineffectual without an affective system

to work upon. And she came to see how the affective system itself is

built around a hard-nut nucleus known as "the indefinable, personal

sense of subjective energy and life."

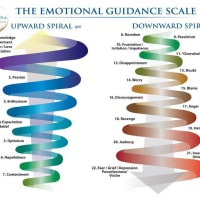

Summarizing, Roberts says, "...self includes the entire affective

emotional network of feelings from the most subtle unconscious stirrings

of energy to the obvious extremes of passionate outbursts. Though

separate from the cognitive system, the affective life so infiltrates

the mind and all its processes that we can never separate our energies

from the cognitive faculties as long as consciousness or self remains."

In the next portion of this chapter entitled Self, Roberts continues to

develop and add to these layers of psycho-spiritual insight.

Self (Part Two)

Based upon her personal discovery, Roberts asserts that self includes

the affective system of willing, feeling, emotion, as these are

expressed along a spectrum of energy ranging from the subtle and

unconscious, to the obvious outbursts of passion. This system is

separate from the cognitive system, but it so greatly infiltrates the

mind (cognitive system) and the entire mental apparatus, that these

energies of the affective system cannot be separated from the cognitive

faculties until the no-self is experienced.

Roberts states that the extent of infiltration by the affective system

is hardly known, as we tend to believe we can be objective about it.

She looks further into the nature of the affective system. She says that

a child feels before it thinks, and in time discovers the separation

between seer and seen, and becomes self-conscious. At this point,

Roberts says, feelings become fused with knowing.

There is more to the understanding of self, she says, than being aware

of self. There must be a sense of personal feeling behind it, which

says, "this is me," "I am myself." This personal energy becomes a core

feeling, or that which makes us human. And it claims all psychic and

physical energy for its own. But it is only self, Roberts says, and "man

is more than self, more than consciousness."

So when the reflexive mechanism, or self-consciousness, closes down or

ceases to exist, the experience of psychic and physical energy goes as

well; or at least they are not experienced as before. This results in a

sense of weightlessness, of being detached from action, and this sense

continues as long as one notices or chooses to remember life prior to

the disappearance of self-consciousness, or the abilities of mind to

bend upon itself. In time, Roberts says, she acclimated to the lack of

feeling any energy.

Summarizing, Roberts says, "In the history of the self, then, physical

energy comes first, the reflexive mechanism comes next and regards this

energy as its own being. With this recognition a division is created

between physical energy and what we will now call 'self-energy', will,

mental or psychic energy, which some people believe is beyond the

physical realm."

So now instead of only the energy of the body, there arises energy of

the mind, "which resulted when the sense of personal energy infiltrated

the cognitive system to energize its thoughts and acts."

Self, then, is not merely the thinking process; it is the doer, the

experience of energy. Considering that self is the intimacy of

connection between the reflexive mechanism (knowing-self) and the

experience of energy (feeling-self), and that this intimacy is necessary

for life, it is not conceivable, Roberts says, that self can bring about

its demise.

"To think...self can get rid of itself is a contradiction," she says.

"...when the time is ripe," there is no need of self. Self seems to

outgrow its usefulness. This does not mark a falling back to an

infantile form of life, but a leap forward, a seeing of what lies beyond

the self, beyond the fulfilled human potential.

But because self cannot bring about its own demise, intervention by an

outside agent is required. This intervention ideally occurs when one

reaches the limit of human potential, for it is then when one may be

able to live without a self.

Roberts concludes that self is the "way" by which one moves to a higher

life. "Obviously, then," she says, "the purpose of having a self is to

eventually go beyond it."

She compares the oneness of self with God, and the Oneness that remains

when there is no self. The former is an experience relative to the

experiences of fragmentation or lack of wholeness. The latter Oneness is

non-relative, simply indescribable. Yet Roberts admits that a whole

self, a self that is one with God, is a necessary preparation for the

Oneness of no-self.

Self (Part Three)

This is dedicated to my friend David H.

So the core or seed of self "is our deepest experience of life and

energy." Out of this seed grows the affective system, the feeling-self,

the will, emotions and feelings.

Consider a board balanced on a fulcrum, like a child's seesaw ride,

Roberts suggests. The fulcrum is the cognitive system, the knowing-self.

The board is the affective system, the feeling self. The ends of the

board represent the extremes of attraction and repulsion, while the part

closest to the unmoving center represents subtle, unconscious

movements.

Optimum stability exists at the center of the two systems. The

non-contemplative one gains and maintains equilibrium despite forces

that exist to unbalance the whole system.

The contemplative seeks to go a step further and move from awareness of

the center point of equilibrium of the affective system, to the still

point or true center of being (I AM).

Now the will is the center of the affective system, Roberts says, and

the provider of energy for the affective system. Also, underlying the

will is the still point or true center of being. So when the will does

not move, or is free of desire, the affective system does not move, a

state of desirelessness exists, and it is easier to access the

still-point (I AM).

This center or will, can be known independent of the cognitive system,

which also touches the center of the affective system.

Once the contemplative knows the still-point (IAM) and turns attention

there, the movement of the affective system comes to a stop, and there

is a sense of stillness and peace.

The nature of this unitive state is union of human and divine will and

power, so that will is now God's will, not contrary to that. Here is

where one may become further tested by the world. Now situations arise

that would test movement of the will, test the integrity of the unitive

state. The requirement is for attention to be unceasingly on the

still-point (I AM).

What Roberts learned is that while there was no more wavering from

abidance at the still-point, no longer any tipping of the board symbolic

of the affective system, there was still the movement of the

ever-horizontal board up and down. This was Roberts way of saying that

she was tested at her innermost core.

And what she observed and discovered was that there was a gap between

herself and God. What demonstrated this gap was the initial spontaneous

movements in response to life events. These movements were automatic and

harmless, yet mystifying to Roberts, as she was not sure of their

source, whether it was herself, or God, or some subtle instinct.

But these movements demonstrated that there was a gap between herself

and God. Within that gap between the center of the board or affective

continuum, and the still-point (I AM), was the battleground between the

forces of self-preservation and self-extinction. This battleground

appeared to be separate from consciousness and untouchable, not under

one's control or will.

Seeing this battle for what it was, understanding it, the battle simply

ceased. Roberts found that the initial spontaneous movements also

stopped, and the still-point (I AM) was then able to further draw the

affective system into its silence.

When the 'drawing' was complete, the continuum was no more, self was no

more, and the still-point was no more. The gap between the still center

of the affective continuum (self) and the still-point (God) was no more.

Therefore, no self, no God there remained. Only what Is.

Self (Part Four of four)

The affective system, Roberts says, is the cause of all suffering. Out

of it arises all fear, anxiety, and psychological suffering.

It would follow, she suggests, that those who have lost the affective

system, are free of psychological disorders and would have no reason to

seek professional help, and that is why the psychiatric literature has

no description of those who have gone beyond the self.

Among the questions that arise is the concern that the lack of an

affective system might lead to lives that are cold, detached,

robot-like. Roberts says that one has to live the no-self life to

understand it.

She says, "All that need be said is that it is a dynamic, intense state

of taking care of whatever arises in the now-moment. It is a continuous

waking state in which the physical organism remains sensitive,

responsive, and totally unimpaired. When fully adjusted to the dimension

of no-self, nothing is found to be missing or wanting. It is only in the

encounter with other selves that a self or affective system is a

reminder of what >was<."

She says that one of the reasons people cannot imagine life without an

affective system is that few grasp the whole picture of what the

affective system is. It is not merely the extremes of love and hate. It

is personal energy and will, and these giving rise to all desire, and

these desires or expectations coloring our world, our thoughts and

perceptions, our experiences, our spiritual experiences of love, bliss,

lights, visions, sounds, ecstasies, etc.

It is all the self, the affective system. It is who we are fooled into

believing who we are.

So when the affective system, our psychological familiarity, our

spiritual feeling, our desires, our self, falls away, what is left to

serve as a standard? There are no standards, no values, from the

perspective of the no-self.

The no-self needs no values. It is already in the now moment. There are

no options to consider, no standards to consult. The no-self is so empty

that is is empty of love, bliss and joy, and empty of hate, sadness and

evil. It is in the now moment. The practice of virtue is absent. Virtue

is simply present. The bottom line is that the will, which is the core

of the affective system, disappears, and it was will that had put virtue

and vice into motion in the first place.

This was Roberts' major discovery about the self: "that its very nucleus

is the will or volitional faculty." When the affective system first

falls away, it is the will that abruptly goes, and later the emotions

and feelings.

One of the difficult aspects of the journey, then, is acclimating to a

lack of movement of the will, or the complete dissipation of personal

energy. That is why lifelessness and lack of energy were experienced by

her along with the disappearance of the self.

In fact, much of Roberts' journey was the process of becoming accustomed

to life without personal energy (or will) and without the experiences

personal energy draws and gathers. And when personal energy is no more,

perhaps, Roberts suggest, it is easier to see how there would be no

results of that energy: no virtues, no vices.

So there is only living in the now moment, without feelings or practice

of virtue, without struggling or the measuring of action. Roberts says,

"Somehow each moment contains within itself the appropriate action for

each tiny event in life without the need for thought or feeling."

She calls the preceding description, "doing." Because of the extreme

condition out of which "doing" arises, it is very difficult to

understand, and it raises many questions pertaining to ethics, morals,

society, and so on.

>From all this, Roberts asserts, it follows that there is a better way of

knowing a person than by the fruits of their actions (which sounds, and

is, contrary to a Christian standard.) And that better way is by knowing

God, and not by knowing the person at all.

For how can we know another when there is no self, no other, as such?

And how, then, can there be a relationship? Again, this becomes very

difficult to grasp as virtually everyone is dependent upon

relationships, even those who have strong inner resources may not be

strong enough to be independent (not absent) of relationships.

People who are dependent upon relationships tend to view life as an "I"

and an "other" affair. The true Other, and therefore the true "I", is

found by turning within, not outward toward another.

Once wholeness is won by the turning within, then one can withstand

relationships with other people, be truly generous, and be conscious in

love, wanting only growth for the other, whatever that may mean.

And what is the true Other? It is the still-point at the center of our

being. "The real problem in life, then, is not between people, but

between the individual and his true Other," says Roberts.

And so having found the Other, relationships are founded on That. We now

love not the affective, emotional self of the one with whom we are in

relationship, but the true Other, the still-point, God in others.

Roberts admits that is not so straightforward a seeing. First one must

face and see the individual. And, secondly, see God.

It is only after the self disappears that the self in others disappears,

and that only God is seen in the other, and the individual fades into

still-point awareness.

This sameness of seeing God, and the goneness of emotion is not as plain

and boring as it sounds. Roberts points out that infinite varieties of

shapes and forms are made out of the same clay. Even individuality

exists in the absence of self. People with no self, and snowflakes, have

no self.

What is really plain and boring, Roberts says, is the self, the

emotions, self-identity, self-possession, the 'I am this', and the 'I am

that'.

The life beyond the self is more free, open and diverse, as it is

centered in the right place: the still point, the I AM.

Summarizing what she learned about the self, Roberts says that a self is

necessary in order to know, feel, and experience. It protects us against

death. It is necessary for survival and existence.

Just as self is developed, a time comes when it passes and fades away.

This movement, all movement through all steps of growth, is the only

thing that neither changes nor passes away.

The contemplative is one who is aware of the movement, first working at

going with it, later discovering he is effortlessly moving with it,

finally realizing that he is the movement Itself.

Conclusion

Roberts reveals that she had not taken her journey alone, but that her

friend and neighbor Lucille, who was 85 at the time, had also undergone

an experience of losing the self. Lucille understood it to be part of

the aging process, a preparation for death. And the stages Lucille went

through paralleled the experiences of Roberts.

The major differences were that Lucille's loss of self occurred slowly

over a period of years, whereas Roberts' changes were abrupt and within

a narrow time frame of two years; and that for Roberts the mystery lie

in what remains when the self is gone, and for Lucille the mystery lie

in how much of her self she could live without; and for Lucille, the

complete loss of self meant presence in God and the end of her life,

while for Roberts loss of self meant the beginning of life.

Roberts states the two broad views afforded by her spiritual journey.

One is that the loss of self and the realization of what remains is the

second part of a journey to God; The second view is that loss of self is

a natural part of the life span, as one prepares to meet what lies

beyond the self.

Whether the self is lost through the contemplative tradition or as the

result of aging, what lies beyond the self invites one not to an end of

any sort, but to a new beginning.

The contemplative's role in society, she believes, is to tell us about a

transition or crossing over that each one of us will make, that some may

be in the midst of making.

Roberts very briefly compares her experiences to those of the mystics.

She says St. Theresa and St. John of the Cross had glimpses of the

no-self and perceived them as transitory, not a doorway to the greatest

depth.

Only Meister Eckhart, Roberts says, spoke of the step beyond union of

self and God. Eckhart, she says, picked-up where St. Thomas Aquinas left

off. She says the two should be studied together in order to gain

knowledge of a full contemplative system.

The Spanish mystics, Roberts contends, in order to uphold theological

propriety, revealed only as much as Thomistic or speculative confines

would allow.

Roberts points out that the mystic depends upon the separation of God

and self for his mysticism, for his oneness experience that he or she so

values. But the no-self experience becomes the Only God experience, and

with God eternally accessible, where is the mystical experience, the

lights and visions? It is the end of the mystical life and the beginning

of real life.

And that is what Roberts is talking about all along. She repeats that

there is the theologically defined oneness of self with God, known in

its highest category by the mystics; and there is "undefineable

essential Oneness" beyond self and God, which theology does not deal

with. It is the becoming of God, not merely the relationship with God.

These are the two ways of seeing and knowing.

In concluding her book, Roberts states that it clears the ground for

much more to be said about this contemplative movement of the loss of

self and Divine Oneness.

She says she is concerned for others who may find themselves moving

beyond the mystical union, beyond the union of self and God. And she

feels it is a grave mistake to think that mystical union is the final

stage.

She urges the mystic to release the experience of unity and all the

feelings associated with it, and to move beyond. She urges that any self

at all, even the divine self, must be released.

That crossing of the line into the unknown is done by God alone. The

self never crosses the line, it simply ceases to exist. (Aside: it

reminds of a mug I have that says upon it, "Old waitresses don't die,

they just give up their stations.")

"For if truth be known," Roberts says, "only Christ dies and only Christ

rises."

She quotes Matthew 10:39: "He who seeks only himself brings himself to

ruin, whereas he who brings himself to naught for me discovers who he

is."

Roberts adds that he will discover not only 'who' he is, but 'what',

'where', and 'that' he is, in God, and that outside God, nothing is.

NONDUALITY.COM

THE FIRST INDEPENDENT NONDUALITY SITE

FOUNDED 1997

前の内容:

Bernadette Roberts (バーナデット・ロバーツ) 1931~ (01)

2013-06-10 00:54:26 | 話題 (opinion)

Self

An Outline (Part One)

This is a complex chapter in which layers of insight blend and

(con)fuse, only to find an attempt at separation in her next book: 'What

is Self?'. Of course, that separation is attained by further layers of

insight, but at least that way there's bound to be something for

everyone.

By way of outline, I'll attempt to do some separation for the reader

here, but expect to sense what I sense: that blending of layers of

insight. Help from fellow Roberts watchers is openly sought! Here

goes...

In discussing self, Roberts makes clear that her knowledge of self comes

from the perspective of no-self. Traditionally, self is known by

not-self, which may otherwise be known as the personal unconscious or

the collective unconscious.

She recognizes that her view of self is so different from that of the

traditional view, that it may appear "incomprehensible and

unacceptable."

The true object of consciousness, Roberts says, is consciousness. This

is the knowing-self.

The other dimension composing the whole of consciousness is the

feeling-self, in which the object of consciousness is the senses.

Roberts compares the nature of consciousness and the nature of the

sensory system. The nature of consciousness is that of the self which

arises from the reflexive action of the mind, or the action of the mind

attending to itself. Out of this action the self arises, or thinker,

doer, feeler arises. This is the knowing-self, consciousness attending

to consciousness.

The sensory system looks not inward at itself, but outward to its

environment, for which is stands ready to respond.

The problem here, Roberts declares, is that we may fail to distinguish

between the self and sensory objects in the environment. This occurs

because the sensory objects are not seen as they are; they are seen as

filtered through the mind, and, therefore, as receivers of a stamp of

subjectivity.

This problem exists as long as the self exists, as long as the mind

bends on itself or attends to itself, as long as thinker, feeler, doer,

stand together as self.

The difference between consciousness and the senses becomes clear once

the self is no more, once the mind ceases to bend on itself.

Such was Roberts' experience. When the self disappeared into a void;

when the mind could no longer attend to itself, or look within, the

senses took over without falling into the same void as consciousness.

However, it was not only the self that had disappeared, but God too: the

union forming the Divine Awareness aspect of consciousness had

disappeared. Now it felt as though all life energy had been depleted.

This sense of life, she says, constitutes the feeling-self, which is

subtle energy located at the center of consciousness or center of being,

and whose existence depends upon the knowing-self, even as a planet

depends upon gravitational force for its placement.

It is these two divisions, the knowing self and feeling self, which form

the whole of consciousness.

With the disappearance of self and God, the entire affective system of

feeling and emotion disappeared, for it could not be kept in place any

longer.

This disappearance of the affective system, and the recognition that it

could not be resurrected, was the basis for Roberts' feelings of terror.

Once confronted, however, the terror went away and never reappeared.

And Roberts then discovered that the stillness of no-self was not

effected or moved by any terror or element of the unknown at all. She

learned, too, that the mind is ineffectual without an affective system

to work upon. And she came to see how the affective system itself is

built around a hard-nut nucleus known as "the indefinable, personal

sense of subjective energy and life."

Summarizing, Roberts says, "...self includes the entire affective

emotional network of feelings from the most subtle unconscious stirrings

of energy to the obvious extremes of passionate outbursts. Though

separate from the cognitive system, the affective life so infiltrates

the mind and all its processes that we can never separate our energies

from the cognitive faculties as long as consciousness or self remains."

In the next portion of this chapter entitled Self, Roberts continues to

develop and add to these layers of psycho-spiritual insight.

Self (Part Two)

Based upon her personal discovery, Roberts asserts that self includes

the affective system of willing, feeling, emotion, as these are

expressed along a spectrum of energy ranging from the subtle and

unconscious, to the obvious outbursts of passion. This system is

separate from the cognitive system, but it so greatly infiltrates the

mind (cognitive system) and the entire mental apparatus, that these

energies of the affective system cannot be separated from the cognitive

faculties until the no-self is experienced.

Roberts states that the extent of infiltration by the affective system

is hardly known, as we tend to believe we can be objective about it.

She looks further into the nature of the affective system. She says that

a child feels before it thinks, and in time discovers the separation

between seer and seen, and becomes self-conscious. At this point,

Roberts says, feelings become fused with knowing.

There is more to the understanding of self, she says, than being aware

of self. There must be a sense of personal feeling behind it, which

says, "this is me," "I am myself." This personal energy becomes a core

feeling, or that which makes us human. And it claims all psychic and

physical energy for its own. But it is only self, Roberts says, and "man

is more than self, more than consciousness."

So when the reflexive mechanism, or self-consciousness, closes down or

ceases to exist, the experience of psychic and physical energy goes as

well; or at least they are not experienced as before. This results in a

sense of weightlessness, of being detached from action, and this sense

continues as long as one notices or chooses to remember life prior to

the disappearance of self-consciousness, or the abilities of mind to

bend upon itself. In time, Roberts says, she acclimated to the lack of

feeling any energy.

Summarizing, Roberts says, "In the history of the self, then, physical

energy comes first, the reflexive mechanism comes next and regards this

energy as its own being. With this recognition a division is created

between physical energy and what we will now call 'self-energy', will,

mental or psychic energy, which some people believe is beyond the

physical realm."

So now instead of only the energy of the body, there arises energy of

the mind, "which resulted when the sense of personal energy infiltrated

the cognitive system to energize its thoughts and acts."

Self, then, is not merely the thinking process; it is the doer, the

experience of energy. Considering that self is the intimacy of

connection between the reflexive mechanism (knowing-self) and the

experience of energy (feeling-self), and that this intimacy is necessary

for life, it is not conceivable, Roberts says, that self can bring about

its demise.

"To think...self can get rid of itself is a contradiction," she says.

"...when the time is ripe," there is no need of self. Self seems to

outgrow its usefulness. This does not mark a falling back to an

infantile form of life, but a leap forward, a seeing of what lies beyond

the self, beyond the fulfilled human potential.

But because self cannot bring about its own demise, intervention by an

outside agent is required. This intervention ideally occurs when one

reaches the limit of human potential, for it is then when one may be

able to live without a self.

Roberts concludes that self is the "way" by which one moves to a higher

life. "Obviously, then," she says, "the purpose of having a self is to

eventually go beyond it."

She compares the oneness of self with God, and the Oneness that remains

when there is no self. The former is an experience relative to the

experiences of fragmentation or lack of wholeness. The latter Oneness is

non-relative, simply indescribable. Yet Roberts admits that a whole

self, a self that is one with God, is a necessary preparation for the

Oneness of no-self.

Self (Part Three)

This is dedicated to my friend David H.

So the core or seed of self "is our deepest experience of life and

energy." Out of this seed grows the affective system, the feeling-self,

the will, emotions and feelings.

Consider a board balanced on a fulcrum, like a child's seesaw ride,

Roberts suggests. The fulcrum is the cognitive system, the knowing-self.

The board is the affective system, the feeling self. The ends of the

board represent the extremes of attraction and repulsion, while the part

closest to the unmoving center represents subtle, unconscious

movements.

Optimum stability exists at the center of the two systems. The

non-contemplative one gains and maintains equilibrium despite forces

that exist to unbalance the whole system.

The contemplative seeks to go a step further and move from awareness of

the center point of equilibrium of the affective system, to the still

point or true center of being (I AM).

Now the will is the center of the affective system, Roberts says, and

the provider of energy for the affective system. Also, underlying the

will is the still point or true center of being. So when the will does

not move, or is free of desire, the affective system does not move, a

state of desirelessness exists, and it is easier to access the

still-point (I AM).

This center or will, can be known independent of the cognitive system,

which also touches the center of the affective system.

Once the contemplative knows the still-point (IAM) and turns attention

there, the movement of the affective system comes to a stop, and there

is a sense of stillness and peace.

The nature of this unitive state is union of human and divine will and

power, so that will is now God's will, not contrary to that. Here is

where one may become further tested by the world. Now situations arise

that would test movement of the will, test the integrity of the unitive

state. The requirement is for attention to be unceasingly on the

still-point (I AM).

What Roberts learned is that while there was no more wavering from

abidance at the still-point, no longer any tipping of the board symbolic

of the affective system, there was still the movement of the

ever-horizontal board up and down. This was Roberts way of saying that

she was tested at her innermost core.

And what she observed and discovered was that there was a gap between

herself and God. What demonstrated this gap was the initial spontaneous

movements in response to life events. These movements were automatic and

harmless, yet mystifying to Roberts, as she was not sure of their

source, whether it was herself, or God, or some subtle instinct.

But these movements demonstrated that there was a gap between herself

and God. Within that gap between the center of the board or affective

continuum, and the still-point (I AM), was the battleground between the

forces of self-preservation and self-extinction. This battleground

appeared to be separate from consciousness and untouchable, not under

one's control or will.

Seeing this battle for what it was, understanding it, the battle simply

ceased. Roberts found that the initial spontaneous movements also

stopped, and the still-point (I AM) was then able to further draw the

affective system into its silence.

When the 'drawing' was complete, the continuum was no more, self was no

more, and the still-point was no more. The gap between the still center

of the affective continuum (self) and the still-point (God) was no more.

Therefore, no self, no God there remained. Only what Is.

Self (Part Four of four)

The affective system, Roberts says, is the cause of all suffering. Out

of it arises all fear, anxiety, and psychological suffering.

It would follow, she suggests, that those who have lost the affective

system, are free of psychological disorders and would have no reason to

seek professional help, and that is why the psychiatric literature has

no description of those who have gone beyond the self.

Among the questions that arise is the concern that the lack of an

affective system might lead to lives that are cold, detached,

robot-like. Roberts says that one has to live the no-self life to

understand it.

She says, "All that need be said is that it is a dynamic, intense state

of taking care of whatever arises in the now-moment. It is a continuous

waking state in which the physical organism remains sensitive,

responsive, and totally unimpaired. When fully adjusted to the dimension

of no-self, nothing is found to be missing or wanting. It is only in the

encounter with other selves that a self or affective system is a

reminder of what >was<."

She says that one of the reasons people cannot imagine life without an

affective system is that few grasp the whole picture of what the

affective system is. It is not merely the extremes of love and hate. It

is personal energy and will, and these giving rise to all desire, and

these desires or expectations coloring our world, our thoughts and

perceptions, our experiences, our spiritual experiences of love, bliss,

lights, visions, sounds, ecstasies, etc.

It is all the self, the affective system. It is who we are fooled into

believing who we are.

So when the affective system, our psychological familiarity, our

spiritual feeling, our desires, our self, falls away, what is left to

serve as a standard? There are no standards, no values, from the

perspective of the no-self.

The no-self needs no values. It is already in the now moment. There are

no options to consider, no standards to consult. The no-self is so empty

that is is empty of love, bliss and joy, and empty of hate, sadness and

evil. It is in the now moment. The practice of virtue is absent. Virtue

is simply present. The bottom line is that the will, which is the core

of the affective system, disappears, and it was will that had put virtue

and vice into motion in the first place.

This was Roberts' major discovery about the self: "that its very nucleus

is the will or volitional faculty." When the affective system first

falls away, it is the will that abruptly goes, and later the emotions

and feelings.

One of the difficult aspects of the journey, then, is acclimating to a

lack of movement of the will, or the complete dissipation of personal

energy. That is why lifelessness and lack of energy were experienced by

her along with the disappearance of the self.

In fact, much of Roberts' journey was the process of becoming accustomed

to life without personal energy (or will) and without the experiences

personal energy draws and gathers. And when personal energy is no more,

perhaps, Roberts suggest, it is easier to see how there would be no

results of that energy: no virtues, no vices.

So there is only living in the now moment, without feelings or practice

of virtue, without struggling or the measuring of action. Roberts says,

"Somehow each moment contains within itself the appropriate action for

each tiny event in life without the need for thought or feeling."

She calls the preceding description, "doing." Because of the extreme

condition out of which "doing" arises, it is very difficult to

understand, and it raises many questions pertaining to ethics, morals,

society, and so on.

>From all this, Roberts asserts, it follows that there is a better way of

knowing a person than by the fruits of their actions (which sounds, and

is, contrary to a Christian standard.) And that better way is by knowing

God, and not by knowing the person at all.

For how can we know another when there is no self, no other, as such?

And how, then, can there be a relationship? Again, this becomes very

difficult to grasp as virtually everyone is dependent upon

relationships, even those who have strong inner resources may not be

strong enough to be independent (not absent) of relationships.

People who are dependent upon relationships tend to view life as an "I"

and an "other" affair. The true Other, and therefore the true "I", is

found by turning within, not outward toward another.

Once wholeness is won by the turning within, then one can withstand

relationships with other people, be truly generous, and be conscious in

love, wanting only growth for the other, whatever that may mean.

And what is the true Other? It is the still-point at the center of our

being. "The real problem in life, then, is not between people, but

between the individual and his true Other," says Roberts.

And so having found the Other, relationships are founded on That. We now

love not the affective, emotional self of the one with whom we are in

relationship, but the true Other, the still-point, God in others.

Roberts admits that is not so straightforward a seeing. First one must

face and see the individual. And, secondly, see God.

It is only after the self disappears that the self in others disappears,

and that only God is seen in the other, and the individual fades into

still-point awareness.

This sameness of seeing God, and the goneness of emotion is not as plain

and boring as it sounds. Roberts points out that infinite varieties of

shapes and forms are made out of the same clay. Even individuality

exists in the absence of self. People with no self, and snowflakes, have

no self.

What is really plain and boring, Roberts says, is the self, the

emotions, self-identity, self-possession, the 'I am this', and the 'I am

that'.

The life beyond the self is more free, open and diverse, as it is

centered in the right place: the still point, the I AM.

Summarizing what she learned about the self, Roberts says that a self is

necessary in order to know, feel, and experience. It protects us against

death. It is necessary for survival and existence.

Just as self is developed, a time comes when it passes and fades away.

This movement, all movement through all steps of growth, is the only

thing that neither changes nor passes away.

The contemplative is one who is aware of the movement, first working at

going with it, later discovering he is effortlessly moving with it,

finally realizing that he is the movement Itself.

Conclusion

Roberts reveals that she had not taken her journey alone, but that her

friend and neighbor Lucille, who was 85 at the time, had also undergone

an experience of losing the self. Lucille understood it to be part of

the aging process, a preparation for death. And the stages Lucille went

through paralleled the experiences of Roberts.

The major differences were that Lucille's loss of self occurred slowly

over a period of years, whereas Roberts' changes were abrupt and within

a narrow time frame of two years; and that for Roberts the mystery lie

in what remains when the self is gone, and for Lucille the mystery lie

in how much of her self she could live without; and for Lucille, the

complete loss of self meant presence in God and the end of her life,

while for Roberts loss of self meant the beginning of life.

Roberts states the two broad views afforded by her spiritual journey.

One is that the loss of self and the realization of what remains is the

second part of a journey to God; The second view is that loss of self is

a natural part of the life span, as one prepares to meet what lies

beyond the self.

Whether the self is lost through the contemplative tradition or as the

result of aging, what lies beyond the self invites one not to an end of

any sort, but to a new beginning.

The contemplative's role in society, she believes, is to tell us about a

transition or crossing over that each one of us will make, that some may

be in the midst of making.

Roberts very briefly compares her experiences to those of the mystics.

She says St. Theresa and St. John of the Cross had glimpses of the

no-self and perceived them as transitory, not a doorway to the greatest

depth.

Only Meister Eckhart, Roberts says, spoke of the step beyond union of

self and God. Eckhart, she says, picked-up where St. Thomas Aquinas left

off. She says the two should be studied together in order to gain

knowledge of a full contemplative system.

The Spanish mystics, Roberts contends, in order to uphold theological

propriety, revealed only as much as Thomistic or speculative confines

would allow.

Roberts points out that the mystic depends upon the separation of God

and self for his mysticism, for his oneness experience that he or she so

values. But the no-self experience becomes the Only God experience, and

with God eternally accessible, where is the mystical experience, the

lights and visions? It is the end of the mystical life and the beginning

of real life.

And that is what Roberts is talking about all along. She repeats that

there is the theologically defined oneness of self with God, known in

its highest category by the mystics; and there is "undefineable

essential Oneness" beyond self and God, which theology does not deal

with. It is the becoming of God, not merely the relationship with God.

These are the two ways of seeing and knowing.

In concluding her book, Roberts states that it clears the ground for

much more to be said about this contemplative movement of the loss of

self and Divine Oneness.

She says she is concerned for others who may find themselves moving

beyond the mystical union, beyond the union of self and God. And she

feels it is a grave mistake to think that mystical union is the final

stage.

She urges the mystic to release the experience of unity and all the

feelings associated with it, and to move beyond. She urges that any self

at all, even the divine self, must be released.

That crossing of the line into the unknown is done by God alone. The

self never crosses the line, it simply ceases to exist. (Aside: it

reminds of a mug I have that says upon it, "Old waitresses don't die,

they just give up their stations.")

"For if truth be known," Roberts says, "only Christ dies and only Christ

rises."

She quotes Matthew 10:39: "He who seeks only himself brings himself to

ruin, whereas he who brings himself to naught for me discovers who he

is."

Roberts adds that he will discover not only 'who' he is, but 'what',

'where', and 'that' he is, in God, and that outside God, nothing is.

NONDUALITY.COM

THE FIRST INDEPENDENT NONDUALITY SITE

FOUNDED 1997