未だ危機でしょ。

面白いけど、同じことの繰り返し。

そこはかとないネタ切れ感が切ない。

なんかとんでもないことが起こってくれないと、Lame Duckなユーロ危機。

皆飽きてきちゃった感がたまらないけど、ドイツ総選挙が終わるとなんかあるのかな?

要点

ユーロは宗教

ヨーロッパ(ドイツを含む)はドM

英国:ばーか、ばーか、ばーかwww

でしょ?

Is Europe still in crisis?

(ヨーロッパは未だ危機ですか?)

By Jeremy Warner

Telegraph: 8:00PM BST 24 Aug 2013

面白いけど、同じことの繰り返し。

そこはかとないネタ切れ感が切ない。

なんかとんでもないことが起こってくれないと、Lame Duckなユーロ危機。

皆飽きてきちゃった感がたまらないけど、ドイツ総選挙が終わるとなんかあるのかな?

要点

ユーロは宗教

ヨーロッパ(ドイツを含む)はドM

英国:ばーか、ばーか、ばーかwww

でしょ?

Is Europe still in crisis?

(ヨーロッパは未だ危機ですか?)

By Jeremy Warner

Telegraph: 8:00PM BST 24 Aug 2013

"Eurogeddon" was the buzzword on everyone's lips in 2011. But is a euro recovery real or imagined?

2011年、誰もが口にしていた流行語は「ユーロゲドン」でした。でも、ユーロの回復は本物?それとも妄想?

Rewind to two years ago, and it seemed to be all over for the beleaguered euro. Spreads were off the scale, the banking system looked close to collapse, and words such as "eurogeddon" were part of the everyday lexicon. The single currency's obituaries were being widely prepared, while here in the UK they had already been written.

2年前を思い出してみましょう。

ボロボロのユーロのおかげで何もかもお終いのようでした。

金利はとんでもないことになっていましたし、銀行システムは崩壊寸前みたいでしたし、「ユーロゲドン」なんて言葉が普通に使われていました。

統一通貨のための追悼文が広く準備され、ここ英国では既に書き上げられていました。

Originally in a state of denial, even the politicians had by November 2011 apparently accepted the inevitable. Confronted by the announcement of a Greek plebiscite on the terms of the latest bail-out, an exasperated Nicolas Sarkozy, then President of France, broke the final taboo and publicly acknowledged that some countries would be unable to make the cut.

当初は認めなかった政治家までが、2011年11月には、否応ない結末を受け容れました。

最新の支援条件に関するギリシャの国民投票結果を突き付けられ、激怒したニコラス・サルコジ仏大統領は最後のタブーをぶち破り、一部の国は基準を満たすことが出来ないだろうと公で認めてしまいました。

This admission set in train a mass panic in financial markets as the full implications of a break-up began to sink in. If Greece had to leave, then other, bigger distressed economies such as Spain or even Italy might be forced out, too, triggering complete meltdown in Europe's banking system. The economic abyss seemed to beckon.

ユーロ崩壊の影響がじわじわと理解され始めた時に、こう認めたことが金融市場大パニックの引き金を引きました。

ギリシャが離脱しなければならないのなら、スペインやイタリアといったその他のもっと大きな重債務国も放り出されて、ヨーロッパの銀行システムは完全にメルトダウンするかもしれません。

経済の奈落の底が手招きしているようでした。

Now fast-forward to today, and much of Europe's economy is engulfed by a depression of unprecedented intensity, the euro still exists in its original form, and talk of a break-up has receded to the point of virtual invisibility. Not a single member has been forced out. In fact, the currency has even gained a new member – Estonia – and there seems to be a long queue of others apparently keen to sign up. What's more, there are even signs of economic revival. In the second quarter of this year, eurozone GDP rose by 0.3pc, or an annualised rate of 1.2pc. Business surveys last week suggested that this upturn has continued into the third quarter. So can we finally bid farewell to Europe's most serious crisis since the Second World War?

さて、現在まで早送りしましょう。

ヨーロッパ経済の大半は前代未聞の激しい不況に飲み込まれ、ユーロは今も当初の形のままで存在していて、ユーロ崩壊話は殆ど消え去りました。

一つの加盟国も追放されていません。

実際、ユーロは新しい加盟国すら得たのです(エストニア)。

しかも熱心に加盟を望む国の列は長々としているようです。

かてて加えて、景気回復の兆しすら見られます。

2013年第2四半期、ユーロ圏のGDPは0.3%、年率にして1.2%成長しました。

先週の企業の景況感調査によれば、この回復は第3四半期も続くようです。

というわけで、ヨーロッパは遂に第二次世界大戦以来、最も深刻な危機を脱したのでしょうか?

Would that it were so. For the next flashpoint, look again to Greece, site of the original infection. With the German general election looming next month, there's been a determined, though not entirely successful, attempt among eurozone leaders to pretend that the Greek problem has been solved, and that it's all onwards and upwards from here on in. Unfortunately, it is only a matter of months before it rears its head again.

だったら良いんですけどね。

次の発火点として、そもそもの感染源であるギリシャに再び目を向けてみましょう。

ドイツ総選挙が来月に迫る中、ユーロ圏首脳陣は、完全に成功しているとは言えないものの断固として、ギリシャ問題は解決した、未来は明るい、というふりをしています。

残念ながら、数か月もすれば問題は再燃するでしょう。

This article attempts to answer four questions: how the euro has managed to survive thus far; whether the European economy genuinely is on the road to recovery; what still needs to be done to ensure a sustainable and successful monetary union, and how likely it is that these things will be done. None of the answers gives much cause for optimism.

ここでは4つの疑問に答えてみようと思います。

どうやってユーロはここまで生き延びたのか。

ヨーロッパ経済は本当に回復に向かっているのか。

通貨同盟を持続可能にし成功させるために何をしなければならないのか。

そして、これらのことが実施される可能性はどうなのか。

いずれの疑問への答えも楽観的にさせてくれません。

The first question is perhaps most interesting, for the euro's resilience seems to defy Margaret Thatcher's dictum that when politics and economics collide, it's always the economics that will win.

一番興味深いのは、最初の疑問でしょう。

というのも、ユーロの耐久性は、政治と経済がぶつかれば経済が常に勝利する、というマーガレット・サッチャーの格言を否定しているようなのです。

The most important thing to recognise about the euro is that it is primarily a political project, not an economic one. If economics had ruled, then it would never have been attempted in the first place, or not on the ambitious scale embarked upon. Even among supporters of the single currency, there is now widespread recognition that the euro in its current form was at best premature; Europe wasn't ready for monetary union, and as a collection of still proud sovereign nations with very different cultures, legal systems and more, perhaps it never will be. Many of the countries that joined at the turn of the century were nowhere near fit for the euro's disciplines, with inflexible labour markets, bloated welfare systems and endemic levels of corruption. That these economies could happily co-exist with a highly competitive German core was always something of a case of wishful thinking.

ユーロについて認識すべき最重要事項は、ユーロはそもそも経済プロジェクトではなく、政治プロジェクトだということです。

経済プロジェクトであったのなら、そもそも作ろうともしなかったでしょうし、これほど野心的なスケールで作ろうとしなかったでしょう。

統一通貨サポーターの間ですら、現在の形のユーロは良く言って未熟だ、ヨーロッパに通貨同盟はまだ早い、非常に様々な文化、法律制度などを有する今も誇り高い主権国の集合体として、永遠に無理だろうという認識が広がっています。。

世紀の変わり目に加盟した国の多くはユーロの規律を満たすには程遠く、硬直した労働市場と膨張した社会保障制度と慢性的な腐敗を抱えています。

これらの経済が極めて競争力の高いドイツなどのコア諸国と共存することは、常に夢のまた夢なのです。

Yet outside Britain, Sweden and Denmark, everyone appeared desperate to join – it seemed against the spirit of "ever-closer union" to deny them. It was also widely believed that the euro would act as a galvanising force, compelling necessary reform and disciplines.

それでも、英国、スウェーデン、デンマークを除き、誰も彼もが加盟したくてしかたないようであり、これらの国を加盟させないのは「統合推進」の精神に反するようです。

また、ユーロは刺激剤となり、必要な改革や規律を余儀なくさせると広く考えられています。

As a result, the rules were widely manipulated to allow all-comers to join. Reluctantly, Germany went along with the pretence, even though it was more aware than any of the dangers.

その結果、全ての加盟希望国を受け容れるべく、規則は大いに操作されました。

その危険に一番気付いていたものの、ドイツもいやいや付き合いました。

Nevertheless, the euro chugged along happily enough for the first five or six years. The launch was a triumph of German efficiency and planning, and for some formerly highly unstable economies, such as Spain and Italy, the new currency seemed to be an overwhelming positive.

それでも、ユーロは最初の5-6年間は上手くやって来ました。

その発足はドイツの効率と計画の大勝利であり、スペインやイタリアといった、もともと極めて不安定な経済にとっては、新通貨は圧倒的に前向きなもののようでした。

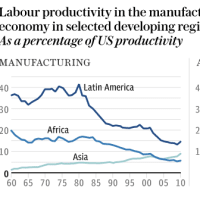

From the start, however, the straitjacket of monetary union was incubating serious problems, imbalances, and in some countries, potentially destabilising credit booms. Far from providing once-wayward economies with the necessary disciplines to succeed, the euro did the reverse, by removing the constraints markets normally impose. Eventually, the single currency became like a pressure cooker ready to explode. With no means of adjustment through the natural market remedy of free-floating exchange rates, major trade and capital imbalances established themselves. Low interest rates led to construction and consumer booms in the eurozone periphery, adding to wage inflation and making deficit nations ever less competitive against the German core. These deficits were financed by a matching savings glut in surplus nations.

しかし、当初から金融同盟の拘束服は深刻な問題、不均衡、そして一部の国では不安定化をもたらしかねない信用ブームを生み出しました。

気まぐれな経済に、成功のために必要な規律を提供するには程遠く、ユーロはいつもの市場に対する規制を排除して、その真逆を行いました。

最終的に、統一通貨は爆発寸前の圧力鍋のようになってしまいました。

自由変動為替制度という市場の自然治癒力による調整力もなく、大規模な貿易不均衡と資本不均衡が出来上がりました。

低金利はユーロ圏周辺国に建設、消費ブームを引き起こし、賃金上昇を煽り、債務国のドイツに対する競争力を益々衰退させました。

このような債務の財源は、黒字国の過剰貯蓄でした。

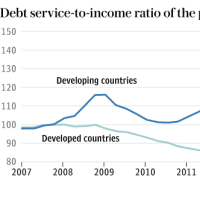

The banking crisis cut these flows off, further weakening the banks in deficit nations and creating a parallel sovereign debt crisis. Europe seemed to be in meltdown.

銀行危機はこれらの流れを断ち切り、債務国の銀行を更に弱体化させ、同時にソブリン債務危機を生み出しました。

ヨーロッパはメルトダウンしているようでした。

Yet though much criticised for a slow and inadequate response, the reality is that Europe has moved with a quite surprising degree of resolve and effectiveness to patch up the project. No one would pretend that the raft of institutions and initiatives put in place to keep the show on the road does any more than paper over the cracks, but given the obvious difficulties of achieving consensus between 17 member states with very different priorities and interests, progress has been remarkable.

とはいえ、対応の遅さと不適切さに対して非常に批判されたものの、現実には、ヨーロッパは驚くほどの決意と手際の良さを以って、ユーロ・プロジェクトを応急処置すべく動きました。

プロジェクトを存続させるために投入された数多の制度やイニシアチブが、亀裂を紙で覆い隠す以上のことはしていない、ということは誰もが認めることです。

しかし、優先事項や利益の非常に異なる17加盟国で合意をまとめることの明らかな難しさを考えれば、素晴らしい進歩でした。

A bail-out fund was quite quickly established and applied to countries denied market access. In the teeth of fierce opposition from the German Bundesbank, the European Central Bank has also begun to operate like a proper central bank should, by offering unlimited liquidity to the banking system and promising to do the same in sovereign bond markets should governments need it. Together, these measures have succeeded in calming the storm.

支援基金はかなり迅速に立ち上げられ、市場から資金を調達出来なくなった国に融資されました。

ドイツ中銀の猛反対にも拘わらず、ECBも銀行システムに無制限の流動性を提供したり、政府が必要とした場合にはソブリン債市場でも同じことを約束したりして、まともな中央銀行のように動き始めました。

これらの対策によって、嵐は鎮まりました。

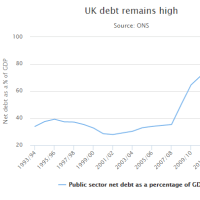

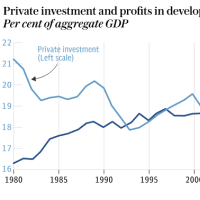

But although these actions have undoubtedly bought time, they have not addressed underlying problems of solvency, competitiveness and imbalances in trade. Furthermore, the austerity programmes imposed on eurozone nations in an effort to halt the rise in sovereign indebtedness has deepened the economic malaise, causing unemployment in deficit countries to reach socially intolerable levels.

しかし、上記の対策は確かに時間を稼いだものの、支払い能力、競争力、貿易不均衡といった根本的な問題には取り組んでいません。

その上、政府の債務増大を阻止するためにユーロ諸国に課した緊縮政策は、経済危機を悪化させて、重債務国の失業率を社会的に容認不可能な水準にまで押し上げました。

Yes, some sort of a recovery seems to be establishing itself – albeit one focused mainly on the already relatively robust German core. In the depression-engulfed periphery, it is more a case of the rate of contraction merely slowing.

確かに、回復のようなものは確立しつつあるようです…まあ、既に比較的堅調なドイツに注目してしまいますが…。

どちらかといえば、不況に飲み込まれた周辺国は、縮小速度が鈍化している状況です。

In Spain, where unemployment is at a scarcely believable 27pc; in Greece, where more than half of the nation's youth is unemployed; and in Ireland, where property prices have crashed, there is little to cheer about.

スペインでは、失業率が27%という信じ難い水準にあり、ギリシャでは若年層の半分以上が失業中であり、アイルランドでは不動産価格が暴落しており、喜ぶような理由は殆どありません。

What cannot be denied, however, is that none of this seems to have shaken political, or even popular, faith in the euro. Here in Britain, we find it impossible to understand why any nation should wish to inflict such punishment on itself. But to many Europeans, the euro is about so much more than a mere monetary mechanism. However malfunctioning it might be, it also seems to represent liberation from past tyrannies, modernity, relevance, and that most precious thing of all, European cohesion and solidarity after centuries of warring destruction.

とはいえ、否定出来ないことがあります。

それは、このいずれも政治的、または世論のユーロへの信仰を揺るがしていないらしい、ということです。

ここ英国では、国がそんな処罰を自国に行いたいと思う理由が到底理解出来ません。

しかし多くのヨーロッパ人にとって、ユーロはただの通貨制度ではないのです。

どれだけ機能不全であろうが、ユーロは過去の独裁者からの解放、近代化、関連性、そして何よりも、数世紀の対立による破壊の後の、ヨーロッパの結合と団結を表しているらしいのです。

It has become something of a cliché to call the euro a religion, but few other words better describe its blind disregard for economic realities. People want to believe. There is another reason, too, why it has held together – fear of the consequences of leaving.

決まり文句のように、ユーロは宗教と呼ばれるようになりましたが、経済的な現実のスルーっぷりをこれ以上に良く表現する言葉は殆どありません。

人々は信じたいのです。

そして、ユーロが維持されている理由はもう一つあります。

それは離脱した結果への恐怖です。

Even the deprivations of depression, loss of fiscal sovereignty, and in some cases the removal of democratically elected governments, seem preferable to the economic chaos that would undoubtedly await any exiting country. More solvent members are equally wary of the crippling losses any exit might impose on their own banking systems. There is a sense in which countries would not be allowed to exit even if they wanted to.

不況の苦しみ、財政主権の喪失、そして場合によっては民主的に選挙で選ばれた政府の排除ですら、ユーロを離脱する国を間違いなく待ち受ける経済的混乱よりはマシのようです。

より財政的に健全な国も、離脱が自国の銀行システムに与えるかもしれない巨額の損失を同じくらい警戒しています。

離脱を望んでも認められない国には、それなりの意味があるのです。

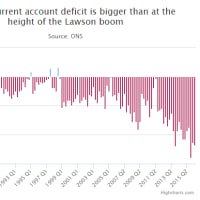

In any case, the patient has been prevented from dying on the operating table, but only to relapse into a state of chronic, long-term illness. Current account deficits have been closed – even Greece is now back in surplus – but only via the brutality of stifling internal demand, causing unemployment to rocket. This in turn has further increased the real burden of public and private indebtedness. If shrinking the economy counts as improved competitiveness – which is what Olli Rehn, Europe's economic commissioner, implies when he says that policy is working – then things really have reached a pretty pass.

いずれにせよ、患者は手術台で死なないようにされていますが、死なないまでも慢性的で長期的な病に戻るだけなのです。

経常赤字は解消されました(ギリシャですらもう黒字に戻りました)が、それは失業率を青天井に上昇させる内需崩壊によってなのです。

これは次に、官民両方の実質債務負担を一層増大させています。

縮小する経済が競争力を改善しているとされるのなら(オッリ・レーン経済・通貨担当委員は政策が上手く行っているなどとのたまわった時に、そうほのめかしているわけですが)、確かに合格点に達したということになります。

With economic contraction doubling up the task, and pain, of deficit reduction, there has of late been some paring back of the austerity agenda.

経済の縮小は債務削減の負担と痛みを倍増させており、最近は緊縮政策がやや縮小されました。

Most countries have been given more time to reach deficit reduction targets. But since they weren't going to meet them anyway, this only recognises a practical reality, rather than amounting to a significant change of heart or policy.

殆どの国は財政赤字削減目標の達成期間延長を認められました。

しかし、どうせ達成しないのですから、これは大きな心変わりや政策転換というよりも、現実を認めたに過ぎません。

Europe still has no convincing answer to destructive levels of unemployment. Nor does it offer debt-encumbered peripheral economies a plausible path back to growth.

ヨーロッパは、破壊的水準の失業率への納得のいく回答を出していません。

また、債務に苦しむ周辺国が成長に立ち戻るための、まともな道筋も提示していません。

Some hedge fund managers believe that once safely re-elected, Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, will finally feel safe enough to provide the kind of leadership necessary to bring about a sustainable monetary union. Such measures must include fairly rapid movement towards a fully-functioning banking union, with a single bail-out mechanism, common deposit insurance and a unified resolution regime.

一部のヘッジファンド・マネジャーは、アンゲラ・メルケル独首相が無事再選を果たせば、持続可能な通貨同盟を作るために必要な指導力を提供出来るだけの安心感を遂に得るだろうと考えています。

それには、全面的な銀行同盟、統一支援機構、共通預金保険、統一決済制度の設立へのかなり急速な動きが含まれなければなりません。

Some form of sovereign debt mutualisation is also required to stabilise markets and bring about the requisite degree of burden-sharing between creditor and debtor nations. None of these things would be possible without the political institutions to give them democratic legitimacy. Yet there is nothing in the German chancellor's rhetoric or policy record to think any of them remotely likely.

何らかのソブリン債の相互化も、市場を安定させて債権国と債務国の間で必要なレベルの負担共有をもたらすために必要です。

このいずれもそれに民主的正当性を与える政治制度なしには不可能でしょう。

それでも、ドイツ首相の言葉にも政策にも、その可能性を僅かでも想像させるものは何もありません。

A cautious politician by nature, there is no evidence that Merkel might be considering such a revolutionary series of changes, even if she thought them appropriate, and there is even less evidence of that. For her, the euro is Germany's new Deutschemark. A certain amount of accommodation and compromise is regarded as necessary, but there are red lines beyond which she will not tread.

本質的に慎重な政治家のメルケルが、そのような革命的な変化の数々を検討しているかもしれない、という証拠は一切ありませんし、たとえ彼女がそれを適切だと思っているとしても、その証拠は一層見受けられません。

彼女にとって、ユーロはドイツの新ドイツ・マルクなのです。

或る程度の寛容と妥協は必要だと考えられていますが、彼女が限界を超えることはありません。

But hasn't her position throughout this crisis been characterised by retreat? This is true enough. On a number of occasions she has dug in her heels, only eventually to be pushed into more concessions.

とはいえ、今回の危機を通じた彼女のポジションは、退却という文字が打倒ではないでしょうか?

これはその通りです。

何度も何度も彼女は踏み留まりましたが、結局は更なる妥協を余儀なくされました。

Another such denouement is threatened soon after she is re-elected, with the epicentre of the crisis returning to its old stamping ground, Greece. Athens needs both more money on top of existing programmes and a further restructuring to stand any chance of reaching debt sustainability. Throughout the election campaign, Ms Merkel's Christian Democrats have studiously tried to avoid all discussion of this politically toxic issue. When it could be avoided no longer, her finance minister, Wolfgang Schaeuble, mentioned it only to insist that although another programme for Greece was inevitable, there could be no question of further debt forgiveness.

またまたいつもの場所、つまりギリシャが危機の震源地となって、彼女は再選直後にまたまたそのようなことになりそうです。

ギリシャ政府は既存の支援融資のお代わりと、債務を持続可能にするために必要な構造改革のお代わりが必要です。

選挙運動を通じて、メルケル夫人のキリスト教民主同盟は、この政治的に猛毒な問題の議論を徹底的に回避しようとしています。

これ以上回避不能になると、ウォルフガング・ショイブレ独財務相が、更なるギリシャ支援は避けられないが追加の債務免除は言語道断だろう、と言い張るだけでした。

This is not what the International Monetary Fund, or indeed Germany's own Bundesbank, believes. A recently leaked Bundesbank report on the issue observed that not only would there have to be further restructuring, but since virtually all Greek sovereign debt was now owned by eurozone bail-out funds and the European Central Bank, the next write-off would obviously have to involve previously immune official creditors.

IMFもドイツ中銀も、そう考えてはいません。

つい先日リークされたドイツ中銀のギリシャ追加支援問題に関するレポートによれば、更なる構造改革が必要というだけでなく、ほぼ全てのギリシャ債は今やユーロ圏の支援基金とECBが抱えているのだから、次の償却にはこれまで損害を免れていた公の債権者も巻き込まれざるを得ないそうでうs。

The Greek bail-out would thereby transition from the present charade of lent money, which will at some stage be repaid, to an outright fiscal transfer. This would be a breach not just of European treaties, but more significantly, the German constitution.

ギリシャ支援は、従って、いずれ返済される融資という現在の茶番劇から、全面的な財政移譲に変わるのです。

これは欧州条約違反と言うだけでなく、もっと重大なことに、ドイツ憲法違反になるのです。

On several levels, then, the belief that the eurozone crisis has gone away, or even that Europe is on the mend, is just more wishful thinking.

そうなれば、いくつかの意味において、ユーロ危機は解消された、またはヨーロッパは回復に向かっているという考えも、ただの妄想に過ぎなくなります。