Mass immigration has made Britain a less competitive economy

(大量移民のおかげで英国経済は競争力を失った)

By Jeremy Warner

Telegraph: 9:00PM BST 02 Sep 2013

(大量移民のおかげで英国経済は競争力を失った)

By Jeremy Warner

Telegraph: 9:00PM BST 02 Sep 2013

When Mark Carney went to Nottingham last week to make his first speech as Governor of the Bank of England, media attention focused, naturally enough, on his reference to Jake Bugg, who we are told is a pop singer of some sort. Amazingly, Mr Carney had been to one of his gigs.

マーク・カーニー英中銀総裁が先週、イングランド銀行総裁就任後初めてのスピーチを行うべくノッティンガムへ行った時、メディアは、まあ当然のことながら、ジェイク・バッグに関する発言に釘付けでした(ウタウタイらしいですね)。ビックリなことに、カーニー総裁は彼のコンサートに行ったことがあったのです。

Yet Mr Carney's more serious point was that UK productivity, which has been trailing other major advanced economies for decades, is no higher today than it was in 2005, when Mr Bugg got his first guitar. This appears to be the longest period of stagnation in UK productivity growth on record. Economists have widely described this phenomenon as a "puzzle", a word they tend to use for any trend that breaks with past norms.

でも、カーニー総裁がもっと真剣に指摘したことは、何十年も前から主要先進国に後れを取っている英国の生産性は、バッグ氏が初めてギターを手に取った2005年よりも今の方がましだってことです。

この生産性の低迷期間は史上最長みたいですね。

エコノミストはこぞってこれを「謎」だと言ってますが、エコノミストってのは今まで基準に外れる傾向は何でもかんでも謎扱いするものです。

To most of us, however, it doesn't seem in the least bit mysterious – it's basically about the triumph in public policy of demand management over serious supply side reform. Unfortunately, this has got worse since the financial crisis began, not better.

でも僕らの大半にとっちゃ、ちっとも謎なんかじゃありませんから。

基本的に、需要抑制政策が供給管理改革に勝っちゃったってことです。

不運なことに、金融危機が始まってからというもの、これは悪化する一方で、ちっとも改善しやしません。

Demand stimulus through monetary and fiscal policy is the politically easy option when an economy hits the buffers and perhaps vital in preventing a contraction turning into a depression but, as Britain's nascent recovery gathers pace, it is worth reiterating that it doesn't of itself lead to sustainable long-term growth or to rising living standards. These require more difficult choices.

金融財政政策による需要押し上げは、経済がバッファーに突き当たってる時には、政治的には楽なオプションですし、景気縮小が不況にならないようにするには重要かもしれないのですが、英国の初期段階にある景気回復が加速する中、それそのものが持続可能な長期的成長や生活水準の向上をもたらすもんじゃないんですよ、ってことは繰り返すに値しますね。

これにはもっと難しい選択を要するのです。

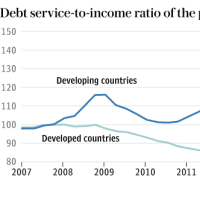

An OECD assessment of the UK economy earlier this year attributed Britain's poor productivity record since the crisis began to a number of factors, all of which are no doubt part of the explanation. To an extent, it's plainly linked to the UK's still impaired banking system, which, as Ben Broadbent, a member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, has argued, hampers the reallocation of capital across sectors.

今年先のOECDによる英国経済評価は、危機勃発後の英国の生産性の低迷の原因を多くの要因のせいだとしており、その全てが原因の一部であることは疑いようもありません。

或る程度までは、英国の未だにボロカスな銀行システムと繋がっているのは明白です。

イングランド銀行金融政策委員会のベン・ブロードベント理事が主張しているように、様々な分野で資本の再配分が行われるのを邪魔する、銀行システムです。

Recessions normally weed out weaker companies and industries, allowing stronger, more productive ones to thrive more effectively. Reluctance to recognise bad debts, for fear of what this might do to banking solvency, has got in the way of this process. Easy monetary policy has also supported the overstretched, which again disrupts the Darwinian disciplines of market forces.

通常、不況は弱小企業や弱小産業を潰して、より強く、より生産性の高い企業や産業がより効率的に儲かるようにしてくれます。

支払い能力への影響を危惧して不良債権を認識しようとしないことが、このプロセスを邪魔しています。

金融緩和政策もこのやり過ぎを助長しまして、これまたダーウィン的な市場原理の働きを邪魔しています。

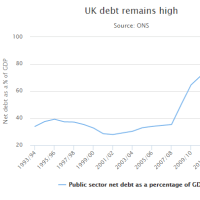

As we now know, trend growth ahead of the crisis wasn't in any case as good as Labour made out; a lot of it was down simply to financial and housing market froth, now blown away by the banking implosion.

今では皆知ってますが、危機前の成長傾向は、労働党が吹聴してるほど良くなかったんですよ。

殆ど金融市場と住宅市場のフロスのおかげじゃありませんか。

今じゃそれも銀行崩壊で吹き飛ばされてますけどね。

Hoarding of skilled labour, declines in North Sea oil production and statistical omissions in capturing the growth in Britain's digital economy, may also have played their part.

高技能労働者の囲い込み、北海油田の生産量減少、英国のデジタル経済の成長記録におけるデータ脱漏も、一役買っていたかもしれません。

Yet none of these things adequately explains Britain's dismal long-term productivity performance.

でも、この中のどれも英国のだらだらと低迷する生産性をきちんと説明していません。

In the search for answers, I want to highlight two other aspects of the problem – the negative impact of mass immigration on productivity and the failure to address simple supply side deficiencies in planning, education, infrastructure, public sector efficiency, the tax system and a perennially weak export performance.

答えを求めて、僕はこの問題の2つの見方にスポットを当てたいと思います。

つまり、大量移民の生産性に対する悪影響と、供給側の計画下手、教育、インフラ、公共部門の効率性、税制、貿易パフォーマンス万年低迷への対応に失敗したことです。

On the whole, business leaders tend to support an open door immigration policy, which helps address skills shortages in key industries. But, more particularly, it also puts downward pressure on wage costs. The effect is similar to having permanently high levels of unemployment, since it creates an inexhaustible supply of cheap labour.

財界のリーダーは総じて、主要産業の技術不足への対応を助けてくれる放置プレーの移民政策を支持する傾向があります。

でも、とりわけ、それは賃金コストを抑え込んでくれるのです。

その効果は万年高失業率と似ていますが、それというのも、これは安価な労働力を無尽蔵に供給してくれるからです。

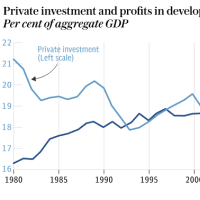

This may or may not be good for corporate profits but it is certainly not good either for productivity or for living standards among low and middle income earners. By making labour cheap, it removes a powerful incentive to productivity gain.

これは企業の利益にとって良いことかもしれないしそうじゃないかもしれませんが、生産性やら低中所得者層の生活水準にとってロクでもないことなのは確かですね。

労働を買い叩くことで、生産性を向上させよう!っていう強力なインセンティブをなくしちゃうんですから。

To see why this is the case, look at what's happened since the crisis began six years ago. During this period, more than 1m private sector jobs have been created, a remarkable achievement given the collapse in output. This has helped keep unemployment much lower than it would otherwise be, which is plainly to be applauded, but it has come at the expense of real incomes.

どうしてこうなっちゃうのか?

危機が起こった6年前からどんなことが起こったか、考えてみてください。

この期間、民間で働く人100万人以上が失業して、生産を見事なまでに減らしてくれました。

おかげさまで、さもなければ大変なことになっていた失業率も大いに低くなりましたし、まあ、これは率直にめでたいんですが、でも、実質所得を犠牲にしてそうなったわけです。

Much of the job creation has been in low-income or part-time employment. Real incomes have experienced their worst squeeze since the 1920s. Yet this is not just a recent phenomenon. The squeeze on real incomes, particularly at the lower end of the scale, pre-dates the crisis.

出てきた求人だって殆どが低所得だかパートタイム。

実質所得は1920年代以来最悪の締め上げを経験したわけです。

それでも、これはつい最近の現象じゃありませんから。

実質所得の締め上げ、特に低所得者層は、危機の前からの話ですよ。

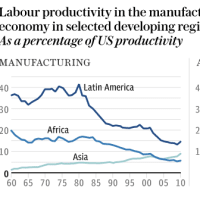

Foreign competition, both in the form of immigration and imported goods and services, has been a big constraint on wage growth. This, in turn, has limited the incentive for efficiency gain. Cheap labour has become a substitute for investment in plant, machinery, training and research and development.

移民と輸入品・サービスという形での海外との競争は、賃金の上昇を大いに邪魔しています。

そしてこれは、効率化のインセンティブを制限しています。

安価な労働力は工場、機械、トレーニング、R&Dの代替品になってしまいました。

When the last administration boasted of the umpteenth successive quarter of successive growth, it neglected to say that this was largely the result of population growth. Income per head was becoming progressively becalmed.

前政権は、連続四半期成長の連発を自慢していた頃、これが主に人口増加の結果だとは言いませんでした。

国民一人あたりの所得は徐々に増えなくなりました。

Britain is an open economy that certainly needs to be in the market for top international talent. Yet high levels of low-end immigration have been, at best, a zero sum game and, by holding back necessary investment in the future, possibly quite a negative economic influence.

英国は、優秀な国際的人材を得るために、確実に市場になければならないオープン・エコノミーです。

にも拘らず、大量の低技能移民は良くいってもゼロ・サム・ゲームですし、将来のために必要な投資を抑制することによる、相当な経済的悪影響である可能性があります。

No free market liberal would argue the case for preventing employers from hiring foreign labour but there are other forms of state intervention that might indeed be appropriate were it not for the fact that the European Union makes them unlawful – for instance, imposing levies on use of cheap foreign labour.

会社が外国人労働者採用の阻止を擁護する自由市場リベラル派などいませんが、EUがこれを非合法としていなければ本当に適切かもしれない他の形での政府の介入はあります(安価な外国人労働力の使用に対する課税など)。

By making low skill employment more expensive, the levy system would provide a powerful incentive for productivity gain in construction, retail, social care and other largely domestically bound industries. These levies could then be channelled back into tax incentives for training and other forms of business investment.

低技能労働者の雇用をもっと高くつくものにすることで、課税制度は建設、小売り、ソーシャルケア、その他主に国内で行われる産業での生産性改善に強力なインセンティブを与えるでしょう。

これらの税金は、トレーニングなどの企業投資に対する税優遇措置として還元することが可能です。

In any case, if living standards are to start growing again, employers must relearn the virtues of doing more with fewer workers. Productivity gain can only properly occur if more efficient and innovative companies are allowed to put poorly performing ones out of business. Relying on population growth, and the falling unit labour costs it brings about, to stay competitive is a road to nowhere.

いずれにせよ、生活水準がまた改善し始めれば、会社はより少ない人数でより大きな生産性を出すという美徳を再度学ばなければなりません。

生産性の向上は、より効率的かつ技術革新的な企業がそうではない企業を廃業に追い込めなければ、きちんと実現し得ないわけです。

競争力の維持を、人口の増加だの、それがもたらす単位労働コストの低減だのに頼ることは、行き止まりの道です。

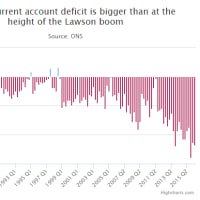

The second issue with productivity is that of an economy which has become unduly reliant on domestic demand. Why chase foreign markets, which require world class levels of competitiveness, when there is the easy option of credit-fuelled domestic demand to fall back on?

2つ目の生産性問題は、内需に過度に依存するようになってしまった経済の生産性です。

信用ジャブジャブになった内需なんてカモがいるのに、世界レベルの競争力を要する海外市場なんて狙うわけないでしょ?

Time and again, the UK has ducked difficult supply side reform in favour of the palliative of demand stimulus. Such measures were plainly important in the early stages of the crisis, when they helped prevent a depression from becoming entrenched, but their continuation five years after the event is now very likely doing more harm than good.

英国は何度も繰り返し、一時しのぎの需要刺激策を好んで、難しい供給側の改革を回避してきました。

そんな対策も、不況が根付かないようにするのを助けてくれた危機の初期段階では当然必要でしたが、5年経っても続けてるってのは、今や薬よりも毒って感じです。

The Juncker curse (after the Luxembourg prime minister) has it that Western politicians know what needs to be done, they just don't know how to get re-elected after doing it.

ユンケルの呪い(ルクセンブルク首相にちなんだ名前です)は、西側の政治家はすべきことを知っているが、それをやらかした後で再選するすべを知らないだけだ、と言っています。

By the same token, everyone knows that productivity-led growth is the only form of growth worth having, they just can't seem to make the long term decisions necessary to achieve it.

同じように、みんな生産性主導型の成長のみが価値ある成長だとわかっていますが、とにもかくにも、それを達成するために必要な長期的な決断を出来ないだけみたいですね。