Depression Denial Syndrome

(不況じゃないもんシンドローム)

Paul Krugman

NYT:OCT. 2, 2014

(不況じゃないもんシンドローム)

Paul Krugman

NYT:OCT. 2, 2014

Last week, Bill Gross, the so-called bond king, abruptly left Pimco, the investment firm he had managed for decades. People who follow the financial industry were shocked but not exactly surprised; tales of internal troubles at Pimco had been all over the papers. But why should you care?

先週、いわゆる債券王のビル・グロスが、彼が何十年も経営してきた投資会社ピムコを電撃辞任しました。

金融業界ウォッチャーは衝撃を受けましたが、必ずしもサプライズというわけではありませんでした。

ピムコの内紛はマスコミがずーっと伝えてきましたからね。

でも、だからどうしたって感じ?

The answer is that Mr. Gross's fall is a symptom of a malady that continues to afflict major decision-makers, public and private. Call it depression denial syndrome: the refusal to acknowledge that the rules are different in a persistently depressed economy.

どうかしてる理由は、グロス氏の失墜は、官民両方の主要意思決定者に影響し続けている病気の一症状だからです。

これを不況じゃないもんシンドロームと呼びましょうか。

つまり、長期的に不況に陥っている経済ではルールが異なると認めることを認めないってこと。

Mr. Gross is, by all accounts, a man with a towering ego and very difficult to work with. That description, however, fits a lot of financial players, and even the most lurid personality conflicts wouldn't have mattered if Pimco had continued to do well. But it didn't, largely thanks to a spectacularly bad call Mr. Gross made in 2011, which continues to haunt the firm. And here's the thing: Lots of other influential people made the same bad call ― and are still making it, over and over again.

グロス氏は根っからのエゴの塊で一緒に働き辛い人だ、と皆が口を揃えます。

でも、それって沢山のファイナンシャル・プレーヤーに当てはまるし、ピムコが上手くやり続けていたらどんだけヤバい性格だって関係なかったでしょうよ。

だけど、グロス氏が2011年にやらかして未だにピムコを脅かし続けている超ど級の大ポカが一番の原因となって、上手くやり続けられなくなってたんですね。

問題はですね、他にも沢山の影響力のある人が同じ大ポカをやらかしました…その上、何度も何度も何度も未だにやからし続けているんです。

The story here really starts years earlier, when an immense housing bubble popped. Spending on new houses collapsed, and broader consumer spending also took a hit, as families that had borrowed heavily to buy houses saw the value of those homes plunge. Businesses cut back, too. Why add capacity in the face of weak consumer demand?

この話の始まりは実は、ものすっごい住宅バブルがぶっ飛んだ数年前に遡ります。

家を買うために借金しまくった家計が住宅価格の大暴落を目にする中で、新規住宅への支出はなくなり、もっと一般的な消費者支出もやられました。

事業も縮小されました。

消費者需要が細ってるのに何だって増産するっての?

The result was an economy in which everyone wanted to save more and invest less. Since everyone can't do that at the same time, something else had to give ― and, in fact, two things gave. First, the economy went into a slump, from which it has not yet fully emerged. Second, the government began running a deficit, as the economic downturn caused a sharp fall in revenue and a surge in some kinds of spending, like food stamps and unemployment benefits.

その結果が、どいつもこいつも貯金にいそしみ投資を渋る経済ですよ。

誰も彼もが同時にそれを出来ないもんだから、何かが折れなきゃいけなかった…で、実は、2つのものが折れました。

先ず、経済が不況入りしまして、未だに完全脱出は成っていません。

次に、政府が赤字を出し始めました。

景気後退で税収は激減し、フードスタンプやら失業給付金なんかの支出が急増したからです。

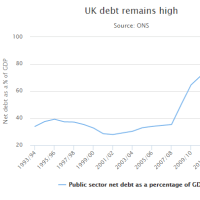

Now, we normally think of deficits as a bad thing ― government borrowing competes with private borrowing, driving up interest rates, hurting investment, and possibly setting the stage for higher inflation. But, since 2008, we have, to use the economics jargon, been stuck in a liquidity trap, which is basically a situation in which the economy is awash in desired saving with no place to go. In this situation, government borrowing doesn't compete with private demand because the private sector doesn't want to spend. And because they aren't competing with the private sector, deficits needn't cause interest rates to rise.

さて、赤字は普通は悪いことだと思いますよね。

政府の借入が民間の借入と競争して、金利を押し上げて、投資の負担を増大して、もしかしたらインフレの足場まで作っちゃうかも。

でも僕らは2008年以降、経済用語で言う「流動性の罠」にはまっている、簡単に言えば経済の中に行き場のない貯金がジャブジャブしまくる状況にあるわけです。

この状況では、民間部門は金を使いたくないんですから、政府の借入は民間の借入需要と競争しません。

それに政府が民間と競争していないから、赤字が必ずしも金利を上昇させるってことにはならないわけです。

All this may sound strange and counterintuitive, but it's what basic macroeconomic analysis tells you. And that's not 20/20 hindsight either. In 2008-9, a number of economists ― yes, myself included ― tried to explain the special circumstances of a depressed economy, in which deficits wouldn't cause soaring rates and the Federal Reserve's policy of "printing money" (not really what it was doing, but never mind) wouldn't cause inflation. It wasn't just theory, either; we had the experience of the 1930s and Japan since the 1990s to draw on. But many, perhaps most, influential people in the alleged real world refused to believe us.

これって一見直観に反した奇天烈話に聞こえるかもしれません。

でも、基本的なマクロ経済分析なんですね。

それに後付講釈でもありませんから。

2008-9年には沢山のエコノミスト(そう、僕も含めて)が、赤字が金利を急上昇させずFRBの「紙幣増刷」政策(本当に刷るわけじゃありませんが、それはさておき)もインフレを引き起こさない、この特殊な不景気について説明しようとしました。

でも理論だけってわけでもなかったんですよ。

1930年代の出来事だとか1990年代以降の日本っていう参考にする経験もありましたから。

とはいえ、現実世界とやらにおられる沢山…多分ほとんどの人は、僕らを信じようとしませんでした。

For a time, Pimco ― where Paul McCulley, a managing director at the time, was one of the leading voices explaining the logic of the liquidity trap ― seemed admirably calm about deficits, and did very well as a result. In late 2009, many Wall Street analysts warned of a looming surge in U.S. borrowing costs; Morgan Stanley predicted that the interest rate on 10-year bonds would soar to 5.5 percent in 2010. But Pimco bet, correctly, that rates would stay low.

しばらくの間、ピムコ(当時のマネジング・ディレクター、ポール・マッカリーは流動性の罠のロジックを解く指導的発言者の一人でした)は、赤字について見事に落ち着いているようでしたし、その結果非常に良くやりました。

2009年下旬、ウォール街アナリストの多くが米国の借入コストが今にも急増するぞとワーニングを出し、モルガン・スタンレーは10年債の金利が2010年には5.5%まで急上昇するだろうと予測しました。

でも、ピムコは、正しくも、金利は低いままだろうと予測しました。

Then something changed. Mr. McCulley left Pimco at the end of 2010 (he recently returned as chief economist), and Mr. Gross joined the deficit hysterics, declaring that low interest rates were "robbing" investors and selling off all his holdings of U.S. debt. In particular, he predicted a spike in interest rates when the Fed ended a program of debt purchases in June 2011. He was completely wrong, and neither he nor Pimco ever recovered.

そして、何かが変わったのです。

マッカリー氏は2010年末にピムコを去りました(最近、チーフ・エコノミストとして復帰したようですが)。

また、グロス氏が赤字ヒステリーに加わって、低金利は投資家を「強盗している」と断言して米国債を全て売り払いました。

具体的に言いますと、FRBが2011年6月に債券買入プログラムを止めたら金利は急上昇するであろう、と予言しました。

彼は完全に間違っていましたし、彼もピムコも二度と回復しませんでした。

So is this an edifying tale in which bad ideas were proved wrong by experience, people's eyes were opened, and truth prevailed? Sorry, no. In fact, it's very hard to find any examples of people who have changed their minds. People who were predicting soaring inflation and interest rates five years ago are still predicting soaring inflation and interest rates today, vigorously rejecting any suggestion that they should reconsider their views in light of experience.

ってことで、これは悪いアイデアは経験によって間違いを証明され、人々の目は開かれ、真実が勝つという教訓的お話なんでしょうか?

なんじゃないんですね。

実際、考えを変えた人を見つけるのは本当に大変なんでしょ。

5年前にハイパーインフレやら金利急上昇を予測した人は今でもハイパーインフレや金利急上昇を予測していて、経験に基づいてお考えを改めるべきじゃなかろうかという提案を猛烈に蹴飛ばしています。

And that's what makes the Bill Gross story interesting. He's pretty much the only major deficit hysteric to pay a price for getting it wrong (even though he remains, of course, immensely rich). Pimco has taken a hit, but everywhere else the reign of error continues undisturbed.

で、ビル・グロス物語を面白くしてるのはそこなんですよぅ。

間違いの代償を払った赤字ヒステリー大物信者って彼だけでしょ(まあ、確かにね、それでも今でも超大金持ちのままだけど)。

ピムコはやられちゃいましたが、それ以外、エラー時代は何事もなく続くのでありました。