本声明発表の発起人の一人、青山学院大学の申教授。

兵器に過度に偏重した国家運営は、このような学生たちの学ぶ権利も侵害する。

防衛費の膨大な増加に抗議し、教育と社会保障への優先的な公的支出を求める声明

2018年12月20日 研究者・実務家有志一同

声明の趣旨

世界的にも最悪の水準の債務を抱える中、巨額の兵器購入を続け、他方では生活保護や年金を引き下げ教育への公的支出を怠る日本政府の政策は、憲法と国際人権法に違反し、早急に是正されるべきである。

1.安倍政権は一般予算で史上最高規模の防衛予算を支出しているだけでなく、補填として補正予算も使い、しかも後年度予算(ローン)で米国から巨額の兵器を購入しており、これは日本国憲法の財政民主主義に反する。

2.米国の対日貿易赤字削減をも目的とした米国からの兵器「爆買い」で、国際的にも最悪の状態にある我が国の財政赤字はさらにひっ迫している。

3.他方で、生活保護費や年金の相次ぐ切り下げなど、福祉予算の大幅削減により、国民生活は圧迫され貧困が広がっている。

4.また、学生が多額の借金を負う奨学金問題や大学交付金削減に象徴されるように、我が国の教育予算は先進国の中でも最も貧弱なままである。

5.このように福祉を切り捨て教育予算を削減する一方で、巨額の予算を兵器購入に充てる政策は、憲法の社会権規定に反するだけでなく、国際人権社会権規約にも反する。

以下、具体的に理由を述べる。

1 膨大な防衛費増加と予算の使い込み

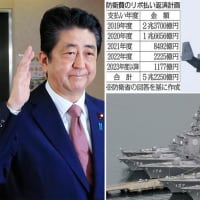

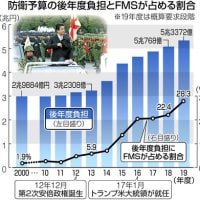

現在、安倍政権の下で防衛費は顕著に増加し続け(2013年度から6年連続増加)、2016年度予算からは、本予算単独でも5兆円を突破している。加えて、防衛省は、本来は自然災害や不況対策などに使われる補正予算を、本予算だけでは賄いきれない高額な米国製兵器購入の抜け道に使い、2014年度以降は毎年2,000億円前後の補正予算を計上して、戦闘機や輸送機オスプレイ、ミサイルなどを、米側の提示する法外な価格で購入している。

しかも、これには後年度負担つまり次年度以降へのつけ回しの「ローン」で買っているものが含まれ、国産兵器購入の分も合わせると、国が抱えている兵器ローンの残高は2018年度予算で約5兆800億円と、防衛予算そのものに匹敵する額に膨れ上がっている(2019年度は5兆3,000億円)。米国へのローン支払いが嵩む結果、防衛省が国内の防衛企業に対する装備品代金の支払いの延期を要請するという異例の事態まで起きている(「兵器ローン残高5兆円突破」「兵器予算 補正で穴埋め 兵器購入『第二の財布』」「膨らむ予算『裏技』駆使」「防衛省 支払い延期要請 防衛業界 戸惑い、反発」東京新聞2018年10月29日、11月1日、24日、29日記事参照)。毎会計年度の予算は国会の議決を経なければならないとしている財政民主主義の大原則(憲法86条)を空洞化する事態である。

防衛省の試算によれば、米国から購入し又は購入を予定している5種の兵器(戦闘機「F35」42機、オスプレイ17機、イージス・アショア2基など)だけで、廃棄までの20~30年間の維持整備費は2兆7,000億円を超える(「米製兵器維持費2兆7000億円」東京新聞11月2日)。一昨日、12月18日には政府は、今後5年間の「中期防衛力整備計画」(中期防)を決定し、過去最高となる27兆4,700億円もの防衛予算を盛り込んだ。戦闘機「F35」追加購入も、11月末には、1機100億円超のものを100機購入して計1兆円以上の見込みとされていた(2018年11月27日日本経済新聞)ものが、12月18日には、105機購入し総額は1兆2千億円以上の見込みと、金額がさらに膨れ上がっている(12月19日朝日新聞)。

2 米国のための高額兵器購入による財政逼迫

このような防衛費の異常な膨張について、根源的な問題の一つは、米国からの高額の兵器購入が、トランプ政権の要請も受け、米国の対日貿易赤字を解消する一助として行われていることである。

歳入のうち国債依存度が約35%を占め、国と地方の抱える長期債務残高が2018年度末で1,107兆円(対GDP比で約2倍の196%)に達するという、「主要先進国の中で最悪の水準」(財務省「日本の財政関係資料」2018年3月)の財政状況にある日本にとって、他国の赤字解消のために、さらなる借金を重ねてまで兵器購入に巨額の予算を費やすことは、国政の基盤をなす財政の運営として常軌を逸したものと言わざるを得ない。

また、導入されている兵器の中には、最新鋭ステルス戦闘機「F35」のような攻撃型兵器が多数含まれている。戦闘機が離着陸できるよう海上自衛隊の護衛艦「いずも」を事実上「空母化」することも、12月18日に閣議決定された新防衛大綱に含まれた。これらは、専守防衛の原則を逸脱する恐れがきわめて強い。

政府は北朝鮮情勢や中国の軍備増強を防衛力増強の理由として挙げるが、朝鮮半島ではむしろ緊張緩和の動きが活発化しているし、近隣国を仮想敵国として際限なく軍拡に走ることも、武力による威嚇を禁じ紛争の平和的解決を旨とする現代の国際法の大原則に合致せず、それ自体が近隣国の警戒感を高める、かえって危険な政策というべきである。

3 福祉切り捨ての現状

このように防衛費が破格の扱いで膨張する一方、政府は、生活保護費や年金の受給額を相次いで引き下げている。

生活保護については、2013年からの大幅引き下げに続き、今年10月からは新たに、食費など生活費にあてる生活扶助を最大で5%、3年間かけて引き下げることとされ、これにより、生活保護世帯の約7割の生活扶助費が減額となる。

しかし、削減にあたっては、減額された保護費が最低限の生活保障の基準を満たすのかどうかについての十分な検討がされておらず、厚生労働省の生活保護基準部会の報告書がこの点で提起した疑問は反映されていない。特に大きな影響を受ける母子世帯や高齢者世帯を含め、受給当事者の意見を聴取することも一切されていない。

生活保護基準は、最低賃金や住民税非課税限度額など様々な制度の基準になっているため、引き下げによる国民生活への悪影響は多方面にわたる。

また、年金については、2013年からの老齢基礎年金・厚生年金支給額の減額に続き、長期にわたり自動的に支給額が削減される「マクロ経済スライド」が2015年から発動されており、高齢者世帯の貧困状況は悪化している。

政府は生活保護減額によって160億円の予算削減を見込んでいるが、そもそも、国家財政を全体としてみた場合、この削減は、青天井に増加している防衛費の増加、とりわけ米国からの野放図な兵器購入を抑えれば、全く必要がなかったものである。

日本の国家財政は、米国の兵器産業における雇用の創出と維持のために用いられるべきものではない。国民の生存権よりも同盟国からの兵器購入を優先するような財政運営は根本的に間違っている。

4 主要国で最も貧弱な日本の教育予算

日本は、GDPに占める教育への公的支出割合が、主要国の中で例年最下位である。特に、日本は「高等教育の授業料が、データのあるOECD加盟国の中で最も高い国の一つであり、過去10年、授業料は上がり続けている」。「高等教育機関は多くを私費負担に頼っている。日本では、高等教育段階では68%の支出が家計によって負担されており、この割合は、OECD加盟国平均30%の2倍を超える」(OECD, Education at a Glance 2018)。

給付型奨学金は2017年にようやく導入されたものの、対象は住民税非課税世帯に限られ、学生数は各学年わずか2万人、給付額は月2~4万円にすぎない。大学生の約75%は私立大学で学んでいるが、国の私学助成が少ないため家計の負担が大きいところ、私大新入生のうち無利子奨学金を借りられるのは15%にすぎず(東京私大教連調査)、多くの卒業生は奨学金という名のローン返済に苦しんでいる。「卒業時に抱える平均負債額は32,170ドルで、返済には学士課程の学生で最大15年を要する。これは、データのあるOECD加盟国の中で最も多い負債の一つである」(OECD, supra)。2011年から2016年の5年間で延べ15,338人が、奨学金にからんで自己破産している(「奨学金破産、過去5年で延べ1万5千人 親子連鎖広がる」朝日新聞デジタル2018年2月12日)。

国立大学法人化後、その基盤経費となる運営費交付金も年々削減され(2004年から2016年までで実質1,000億円以上。文部科学省調査)、任期付き教員の増加など大学の教育・研究に支障をきたしている(「土台から崩れゆく日本の科学、疲弊する若手研究者たち これが『科学技術立国』の足元」Wedge Infinity 2017年11月27日)。

高等教育だけではない。教育予算が全体としてきわめて貧弱であり人員が少ないため、公立の小・中・高等学校では半数以上の教員が過労死レベルで働いている(「過労死ライン超えの教員、公立校で半数 仕事持ち帰りも」朝日新聞デジタル2018年10月18日)。

教育に予算を支出しない国に未来はあるだろうか。納税者から託された税金を何にどう用いるかという財政政策において、教育を受ける権利の実現は最優先事項の一つでなければならない。

5 日本は社会権規約に違反している

憲法25条は国民の生存権を保障している。また、日本が批准している「経済的、社会的及び文化的権利に関する国際規約」(社会権規約)は、社会保障についての権利(9条)、適切な生活水準についての権利(11条1項)を認め、国はこれらの権利の実現のために、利用可能な資源を最大限に用いて措置を取る義務があるとしている(2条1項)。

権利を認め、その実現に向けて措置を取る義務を負った以上は、権利の実現を後退させる措置を取ることは規約の趣旨に反する(後退禁止原則)。社会権規約委員会は「一般的意見」で、「いかなる意図的な後退的措置が取られる場合にも、国は、それがすべての選択肢を最大限慎重に検討した後に導入されたものであること、及び、国の利用可能な最大限の資源の完全な利用に照らして、規約に規定された権利全体との関連によってそれが正当化されること、を証明する責任を負う」としている。

このような観点から委員会は、日本に対する2013年の「総括所見」で、社会保障予算の大幅な削減に懸念を示している。また、日本の最低賃金の平均水準が最低生存水準及び生活保護水準を下回っていることや、無年金又は低年金の高齢者の間で貧困が広がっていることにも懸念を表明した(外務省ウェブサイト「国際人権規約」参照)。

今年(2018年)5月には、10月からの生活保護引き下げについて、「極度の貧困に関する特別報告者」を含む国連人権理事会の特別報告者ら4名が連名で、引き下げは日本の国際法上の義務に違反するという声明を発表し政府に送る事態となった。「日本のような豊かな先進国におけるこのような措置は、貧困層の人々が尊厳をもって生きる権利を直接に掘り崩す、意図的な政治的決定を反映している。」「貧困層の人権に与える影響を慎重に検討しないで取られたこのような緊縮措置は、日本が国際的に負っている義務に違反している」。

また社会権規約は、国はすべての者に教育の権利を認め、中等教育と高等教育については、無償教育を漸進的に導入することにより、すべての人に均等に機会が与えられるようにすることと規定している。適切な奨学金制度を設立することも定めている(13条2項)。教育に対する日本の公的支出の貧弱さはこれらを遵守したものになっていない。なお政府は2017年12月に閣議決定した「新しい政策パッケージ」で「高等教育の無償化」を打ち出したが、対象となる大学を選別する不当な要件を付しており問題が大きい。

**************************

後年度負担まで組んで莫大な額の兵器を買い込み国家財政を逼迫させる一方で、十分な検討も経ずに生活保護を引き下げることや、きわめて貧弱な教育予算を放置し又は削減することは、憲法の平和主義、人権保障及び財政上の原則のみならず、国際法上の義務である社会権規約(及び、同様の規定をもつ子どもの権利条約や障害者権利条約など)に違反している。我々は、安倍政権による防衛予算の異常な運営に抗議し反対の意を表明するとともに、教育と社会保障の分野に適切に予算を振り向けることを強く求めるものである。

<呼びかけ人>(五十音順、*発起人)

荒牧 重人(山梨学院大学教授、憲法学・子ども法)

井上 英夫(金沢大学名誉教授・佛教大学客員教授、人権論・社会保障法学)

大久保 賢一(弁護士、日本反核法律家協会事務局長)

小久保 哲郎(弁護士、生活保護問題対策全国会議事務局長)

今野 久子(弁護士)

澤藤 統一郎(弁護士、日本民主法律家協会元事務局長・日本弁護士連合会元消費者委員会委員長)

*申 惠丰(青山学院大学教授、国際人権法学会前理事長、国際人権法学)

田中 俊(弁護士)

谷口 真由美(大阪国際大学准教授、国際人権法学)

角田 由紀子(弁護士)

*徳岡 宏一朗(弁護士、日本反核法律家協会理事)

戸室 健作(千葉商科大学専任講師、社会政策論)

根森 健(神奈川大学特任教授、新潟大学・埼玉大学名誉教授、憲法学)

浜 矩子(同志社大学教授、経済学)

尾藤 廣喜(弁護士、生活保護問題対策全国会議代表幹事)

藤田 早苗(エセックス大学研究員、国際人権法学)

藤原 精吾(弁護士・日本反核法律家協会副会長・日本弁護士連合会元副会長)

吉田 雄大(弁護士)

以上 計18名

<賛同者>(五十音順)

青井 未帆(学習院大学教授、憲法学)

阿部 信行(白鴎大学法学部教授、法哲学・総合人間学)

浅倉 むつ子(早稲田大学教授、労働法学)

浅見 輝男(茨城大学名誉教授、土壌学)

麻生 多聞(鳴門教育大学准教授、憲法学)

阿部 浩己(明治学院大学教授、国際人権法学会元理事長、国際人権法学)

五十嵐 二葉(弁護士)

池内 了(名古屋大学名誉教授、宇宙物理学)

石井 まこと(大分大学教授、社会政策)

石塚 伸一(龍谷大学教授、刑事法学)

石川 裕一郎(聖学院大学教授、憲法学)

石口 俊一(弁護士)

市川 須美子(獨協大学教授、教育法学)

伊藤 周平(鹿児島大学教授、社会保障法学)

伊藤 真(伊藤塾塾長、弁護士)

伊藤 誠(東京大学名誉教授、経済学)

伊藤 芳朗(弁護士)

稲 正樹(国際基督教大学元教授、憲法学)

井上 啓(弁護士)

井上 幸夫(弁護士)

井口 克郎(神戸大学准教授、社会保障・経済学)

井原 聰(東北大学名誉教授、科学史・技術史)

今井 直(宇都宮大学名誉教授、国際人権法学)

今泉 義竜(弁護士)

今川 正章(弁護士)

岩井 信(弁護士)

岩崎 晋也(法政大学教授、社会福祉学)

上西 充子(法政大学教授、労働問題)

上野 千鶴子(東京大学名誉教授、社会学)

上柳 敏郎(弁護士)

内田 樹(神戸女学院大学名誉教授、哲学)

内田 博文(九州大学名誉教授、刑事法学)

梅田 康夫(元金沢大学教授、日本法制史)

浦田 賢治(早稲田大学名誉教授、憲法学)

江夏 大樹(弁護士)

江森 民夫(弁護士)

大久保 佐和子(弁護士)

大竹 寿幸(弁護士)

大西連(NPO法人「もやい」理事長)

大藤 紀子(獨協大学教授、憲法学)

岡崎 敬(弁護士・伊藤塾講師)

岡田 正則(早稲田大学教授、行政法学)

岡田 行雄(熊本大学教授、刑事法学)

岡野 八代(同志社大学教授、政治思想・フェミニズム思想)

小川 隆太郎(弁護士)

小木 和夫(弁護士)

尾﨑 恭一(東京薬科大学客員教授、医療倫理・哲学)

小沢 隆一(東京慈恵会医科大学教授、憲法学)

戒能 通厚(名古屋大学・早稲田大学名誉教授、法学)

垣内 国光(明星大学名誉教授、子ども家庭福祉論)

覚正 豊和 (敬愛大学教授、 刑事法学)

嘉指 信雄(神戸大学教授、哲学)

笠松 健一(弁護士)

加藤 健次(弁護士)

加藤 節(成蹊大学名誉教授、政治哲学)

金子 匡良(法政大学教授、憲法学)

上条 貞夫((弁護士)

上脇 博之(神戸学院大学教授、憲法学)

川口 智也(弁護士)

川島 聡(岡山理科大学准教授、国際人権法学・障害法学)

河合 正雄(弘前大学講師、憲法学)

菊地 洋(岩手大学准教授、憲法学)

岸 朋弘(弁護士)

木島 紗千恵(弁護士)

北見 秀司(津田塾大学教授、哲学・社会思想史)

北村 泰三(中央大学教授、国際法学)

北澤 貞男(弁護士)

君和田 伸仁(弁護士)

木村 康則(弁護士)

清末 愛砂(室蘭工業大学大学院准教授、憲法学)

草場 裕之(弁護士)

楠 晋一(弁護士)

葛野 尋之(一橋大学教授、刑事法学)

楠本 敏行(弁護士)

窪 誠(大阪産業大学教授、国際法学)

黒岩 哲彦(弁護士)

合田 公計(大分大学名誉教授、経済学)

河野 善一郎(弁護士)

伍賀 一道(金沢大学名誉教授、社会政策)

小部 正治(弁護士)

後藤 弘子(千葉大学教授、刑事法学)

児玉 勇二(弁護士)

後藤 道夫(都留文科大学名誉教授、社会哲学・現代社会論)

小林 譲二(弁護士、早稲田大学大学院教授)

小林 節(慶應義塾大学名誉教授、憲法学)

小林 武(沖縄大学客員教授、憲法学)

駒井 重忠(弁護士、鳥取県弁護士会会長)

小森 陽一(東京大学教授、日本近代文学)

小森田 秋夫(神奈川大学教授、比較法学)

齊藤 純一(早稲田大学教授、政治学)

坂本 修(弁護士)

坂本 雅弥(弁護士)

佐々木 光明(神戸学院大学教授、刑事法学・少年司法)

笹沼 弘志(静岡大学教授、憲法学・生活保護法学)

佐藤 潤一(大阪産業大学教授、憲法学)

佐藤 博文(弁護士)

佐藤 学(学習院大学特任教授、教育学)

佐藤 安信(東京大学教授、人間の安全保障)

佐藤 由紀子(弁護士)

志田 陽子(武蔵野美術大学教授、憲法学)

芝池 俊輝(弁護士)

芝田 英昭(立教大学教授、社会保障論)

清水 雅彦(日本体育大学教授、憲法学)

島岡 まな(大阪大学法科大学院教授、刑法)

島袋 純(琉球大学教授、地方自治論・行政学)

志村 新(弁護士)

白井 邦彦(青山学院大学教授、労働経済学)

白藤 博行(専修大学教授、行政法)

須網 隆夫(早稲田大学教授、EU法学・国際経済法学)

菅 俊治(弁護士)

菅原 絵美(大阪経済法科大学准教授、国際人権法学)

菅原 真(南山大学教授、憲法学)

杉浦 ひとみ(弁護士)

鈴木 靜(愛媛大学教授、社会保障法学)

鈴木 亜英(弁護士)

鈴木 勉(佛教大学教授、福祉政策論)

鈴木 博人(中央大学法学部教授、家族法)

青龍 美和子(弁護士)

芹澤 齊(青山学院大学名誉教授、憲法学)

曽我 千春(金沢星稜大学教授、社会保障・社会福祉政策)

空野 佳弘(弁護士)

髙木 和美(岐阜大学教授、社会福祉学、労働・生活問題)

高木 博史(岐阜経済大学教授、社会福祉学)

髙崎 暢(弁護士)

高田 清恵(琉球大学教授、社会保障法学)

高橋 哲哉(東京大学教授、哲学)

髙山 佳奈子(京都大学教授、刑事法学)

滝沢 香(弁護士)

武井 寛(甲南大学教授、労働法)

武村 二三夫(弁護士)

建石 真公子(法政大学教授、憲法学)

田中 明彦(龍谷大学教授、社会保障法学)

谷口 洋幸(金沢大学准教授、国際人権法学・ジェンダー法学)

千葉 眞(国際基督教大学特任教授、政治思想)

津田 玄児(弁護士)

土屋 仁美(金沢星稜大学講師、憲法学)

坪井 節子(弁護士)

寺中 誠(東京経済大学講師、人権論・刑事政策論)

登坂 真人(弁護士)

中川 明(弁護士)

中川 勝之(弁護士)

中川 武夫(中京大学名誉教授、公衆衛生学)

中塚 明(奈良女子大学名誉教授、日本近代史)

中谷 雄二(弁護士)

長友 薫輝(三重短期大学教授、社会保障論)

中野 晃一(上智大学教授、政治学)

中森 俊久(弁護士)

並木 陽介(弁護士)

新倉 修(青山学院大学名誉教授、刑事法学、弁護士)

成嶋 隆(獨協大学教授、憲法学)

新井田 智幸(東京経済大学専任講師、経済思想)

丹生 淳郷(日本科学者会議埼玉支部事務局長、薬学)

西海 真樹(中央大学教授、国際法学)

西崎 文子(東京大学教授、歴史学)

西谷 修(立教大学特任教授、哲学・思想史)

西山 明行(弁護士・日本反核法律家協会理事)

二宮 孝富(大分大学名誉教授、民法学・法社会学)

野澤 裕昭(弁護士)

橋本 佳子(弁護士)

長谷川 悠美(弁護士)

原口 暁美(弁護士)

林 治(弁護士)

半田 久之(司法書士)

秀嶋 ゆかり(弁護士)

平井 康太(弁護士)

平井 哲史(弁護士)

広瀬 訓(長崎大学教授、国際法学)

藤岡 毅(弁護士)

渕上 隆(弁護士)

淵脇 みどり(弁護士)

古橋 エツ子(花園大学名誉教授、社会保障法学)

星野 圭(弁護士)

堀尾 輝久(東京大学名誉教授、教育学)

本庄 十喜(北海道教育大学准教授、日本史)

本田 伊孝(弁護士)

本間 照光(青山学院大学名誉教授、保険論・社会保障論)

牧野 忠康(日本福祉大学名誉教授、保健学)

正木 みどり(弁護士)

益川 敏英(京都大学名誉教授、物理学/ノーベル賞受賞者)

松下 一世(佐賀大学教授、教育学・人権教育学)

松村 高夫(慶應義塾大学名誉教授、社会史)

松山 秀樹(弁護士)

間宮 陽介(青山学院大学特任教授、経済学)

三浦 永光(津田塾大学名誉教授、哲学・社会思想史)

三上 昭彦(明治大学元教授、教育学)

三島 憲一(大阪大学名誉教授、哲学・思想史)

水島 朝穂(早稲田大学教授、憲法学)

水野 和夫(法政大学教授、経済学)

水口 洋介(弁護士)

簑田 孝行(弁護士)

宮本 憲一(大阪市立大学名誉教授、経済学)

武藤 達夫(関東学院大学准教授、国際法学・国際人権法学)

村井 敏邦(一橋大学・龍谷大学名誉教授・弁護士、刑事法学)

村山 裕(弁護士)

元 百合子(大阪経済法科大学客員研究員・大阪女学院大学元教授、国際人権法学)

望月 彰(名古屋経済大学教授、教育学)

本 秀紀(名古屋大学教授、憲法学)

安原 陽平(沖縄国際大学講師、憲法学・教育法学)

柳澤 繁孝(大分大学名誉教授、口腔外科学)

山田 麻紗子(人間環境大学特任教授、司法・犯罪心理学)

山田 由紀子(弁護士)

山本 忠(立命館大学教授、社会保障法学)

雪田 樹理(弁護士)

横湯 園子(中央大学元教授、臨床心理学)

吉田 裕(一橋大学特任教授、日本史)

世取山 洋介(新潟大学教授、教育法学)

脇田 滋(龍谷大学名誉教授、労働法・社会保障法学)

鷲谷 いづみ(中央大学教授、保全生態学)

鷲谷 徹(中央大学教授、経済政策)

渡辺 治(一橋大学名誉教授、政治学・憲法学)

和田 肇(名古屋大学教授、労働法学)

以上 計 209名

【研究者・法曹実務家以外の賛同者】

赤羽根 巖(医師)

莇 昭三(医師、全日本民医連名誉会長)

武田 さち子(一般社団法人ここから未来 理事、教育評論)

藤野 興一(前全国児童養護施設協議会会長・子どもの虐待防止ネットワーク鳥取理事、ソーシャルワーカー)

松本 文六(医師)

みわよしこ(フリーライター)

横川 和夫(ジャーナリスト)

Statement of Protest against the Massive Increase of the Defense Budget: An Urgent Call for Prioritized Public Expenditure on Education and Social Security

[Full text with citations; For distribution in the press conference]

Group of Scholars and Lawyers, 20 December 2018

The Japanese government’s policy of continuing to purchase an exorbitant amount of weapons in order to reduce the trade deficit of the US with Japan, in spite of the fact that Japan has the highest national debt in the world, while cutting social security benefits and neglecting public expenditure on education, is contrary to the Constitution as well as international human rights law, and thus needs to be urgently corrected.

Summary:

1. The Abe administration is not only spending an unprecedented amount on defense under the main budget, but has also resorted to the supplementary national budget to buy an exorbitant number of weapons from the US on loan. This is contrary to the principle of fiscal democracy in the Japanese Constitution.

2. As a consequence of this massive purchase of weapons from the US, designed partly to reduce the US trade deficit with Japan, the fiscal condition of Japan, which has the worst national debt in the world, has become even more constrained.

3. On the other hand, the social security budget has been greatly reduced in recent years, with continuing cuts being made to public assistance benefits and pension benefits, widening the spread of poverty of citizens.

4. In addition, the amount spent on education as a percentage of GDP remains the lowest among industrialized countries, a situation exemplified by the problem of student loans (“scholarships”) and the reduction of management expenses grants to national universities.

5. The government’s policy of allocating massive amounts of money for the purchase of weapons, while cutting down on social security and reducing the education budget, not only runs counter to the social rights provisions in the Constitution but also the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

These five points are explained in greater detail below.

1. Massive Increase in Defense Expenditure and Abusive Use of the National Budget

Under the Abe administration, the defense budget has continued to rise steeply (for six years in a row since 2013), and since fiscal year 2016, it has exceeded 5 trillion yen ($ 44 billion) under the main budget alone. In addition, the Ministry of Defense has resorted to the supplementary national budget, designed originally to be used for natural disasters and measures in response to economic depression, as a loophole to buy expensive US weapons that the main budget cannot cover. Since 2014, the Ministry has piled up supplementary budget requests of approximately 200 billion yen ($ 17.6 billion) each year, and has purchased fighter planes, Ospreys and missiles at an exorbitant price presented by the US.

Furthermore, these purchases include those charged to subsequent years, i.e. made “on loan”. Combined with the purchase of domestic defense products, the bill for loans for weapons charged to the government amounts to 5.08 trillion yen ($ 44.7 billion) for fiscal year 2018 (5.3 trillion yen for 2019), equal to the whole defense budget for the year. This situation seriously undermines the basic principle by which the budget for every fiscal year must be approved by the Diet (Article 86 of the Constitution).

As a consequence of costly payment of loans to the US, an unprecedented situation occurred recently: the Ministry of Defense requested the deferral of payment for defense products from domestic defense industries (see articles in the Tokyo Shimbun, “Heiki Loun Zandaka Go Cho-en Toppa [the Bill for Weapon Loan Exceeds 5 Trillion Yen]”, “Heiki Yosan Hosei-de Anaume: Heiki Kounyu Daini-no Saifu [Filling up the Spending on Weapons with Supplementary Budget: ‘Second Wallet’ for Weapons]”, “Fukuramu Yosan: ‘Urawaza’ Kushi [Mushrooming Budget: Use of a ‘Trick’]”, “Boueisho Shiharai Enki Yousei: Bouei Gyokai Tomadoi Hampatsu [The Ministry of Defense Asks for Deferral of Payment: Embarrassment and Resistance of Defense Industries], 29 October, 1, 24 and 29 November 2018).

According to a calculation by the Ministry of Defense, the cost of maintenance and support for five kinds of weapons purchased or to be purchased from the US (such as forty-two “F35” fighter planes, seventeen Ospreys, and two sets of the Aegis Ashore missile defense system) over twenty to thirty years of usage before being discarded will exceed 2.7 trillion yen ($ 238 billion) (Tokyo Shimbun, 2 November 2018). On top of that, the government is considering an additional purchase of a maximum of 100 F35 stealth fighter planes at a cost of over 10 billion yen each, totaling over 1 trillion yen ($ 8.8 billion) (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 27 November 2018). On December 18th, the government approved the new five-year defense plan assuming record spending of 27.47 trillion yen ($ 242 billion). It was also announced that the number of F35 fighter planes to be purchased would be 105, with the total amount swelling to at least 1.2 trillion yen ($ 8.9 billion) (Asahi Shimbun, 18 December 2018).

2. Constraint on the National Budget Due to the Purchase of Expensive Weapons for the Sake of the US

One of the fundamental questions posed by such an abnormal increase in defense expenditure is that the purchase of expensive weapons from the US is conducted, under pressure from the Trump Administration, as a means of alleviating the U.S. trade deficit with Japan.

As the Ministry of Finance admits (the Ministry of Finance, “Nihon-no Zaisei Kankei Shiryo [Materials Concerning Japan’s Finance]”, March 2018), the financial situation of Japan is “at the worst level among major industrialized countries”, with the amount of long-term debt reaching 1.1 trillion yen ($ 9.7 billion) at the end of fiscal year 2018 (196 percent of the national GDP). Under such conditions, it is totally unacceptable, in terms of administration of the national budget, which represents essential resources for public policies, to spend such a large amount of public money on armaments and increase the national debt even further.

It is to be noted that the weapons thus purchased include numerous products, such as cutting-edge F35 stealth fighter planes, that are utilized for attacks rather than defense. The government also approved transforming the escort ships “Izumo” of the Self Defense Force into an aircraft carrier so that fighter planes may take off and land. There is a serious concern that the use of these armaments will deviate from the principle of self-defense adhered to by previous administrations.

While the government invokes the situation related to North Korea and China’s extension of its military power as justifications for increased defense expenditure, we are, as a matter of fact, witnessing an active movement towards détente on the Korean Peninsula. Resorting to unlimited expansion of military power, assuming that neighboring countries are virtual enemy States, is not consistent with the basic principles of international law prohibiting the threat of force and obliging peaceful settlement of disputes. It is also a dangerous policy in itself that aggravates the sense of wariness held by those countries.

3. Reduction of Social Security Benefits by the Government

At the same time that it is expanding the defense budget to an exceptional degree, the government has also sharply cut down social security benefits one after another.

As regards public assistance, the last safety net for the right to subsistence, it has been decided that the amount of livelihood assistance intended for food and other basic living expenses is to be lowered by a maximum of five percent for the next three years starting from October this year.

However, this cut was carried out without reflecting on those voices questioning whether the reduced amount would meet the minimum level of social protection raised in the reports of the Committee on the Standard of Public Assistance under the Ministry of Welfare and Labor. A process of public consultation for those concerned, including most-affected households such as single-mother households and households of the elderly, was also nonexistent.

As the standard of public assistance benefits is used as a standard in other systems, such as the minimum wage and exemption from the payment of resident tax, a lowering of this standard has a negative impact on the general population in many ways.

As regards pension benefits, following the cuts to the basic old-age pension as well as the employee pension in 2013, a “macro-economic slide” mechanism, which will automatically keep increases in pension benefits below the rate of inflation over the long term, has been implemented since 2015, aggravating the poverty of the elderly.

The government intends to make a budgetary cut of 16 billion yen ($ 140 million) by reducing expenditure on public assistance from this year. However, if we take the national budget as a whole, this measure was far from necessary in light of the sharp rise in defense expenditure, particularly the reckless purchase of expensive weapons from the US.

The national budget of Japan is not to be used for the creation and maintenance of employment in the defense industry of the US. Administering the national budget in a way that prioritizes the purchase of weapons from an ally over the right to subsistence of citizens is fundamentally wrong and unjustifiable.

4. Japan’s Most Inadequate Public Expenditure on Education

Japan ranks the lowest among the major industrialized countries in terms of its public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP. In particular, “Japan has some of the highest tertiary tuition fees among OECD countries with available data, and they have been increasing in the past decade”. “Tertiary educational institutions… rely heavily on private funding: 68 percent of the expenditure is privately funded at this level in Japan, over twice the OECD average of 30%” (OECD, Education at a Glance 2018).

Although a grant-type scholarship was belatedly introduced in 2017, only those who live in households with the lowest income, exempt from the payment of resident tax, are eligible. Barely 20,000 students are chosen among them, and the amount given is only 20,000 to 40,000 yen per month. While nearly 75 percent of university students are enrolled in private universities, only a handful of freshmen (15 percent) may avail themselves of loan-type but interest-free “scholarships”. Many graduates and their families are plagued with the reimbursement of such loans in the name of “scholarships”. “The average debt on graduation is $ 32,170 and repayment can take up to 15 years for students graduating with a bachelor’s degree, one of the highest debt burdens on tertiary graduates across OECD countries with available data” (OECD, supra). A total of 15,338 people were compelled to file for bankruptcy deriving from the problem of “scholarship” between 2011 and 2016 (“Shogakukin Hasan, Kako Gonen-de Nobe Ichiman Gosen-nin: Oyako Rensa HIrogaru [A Total of 15,338 People Went Bankrupt Due to Scholarship: Spread of Chain Reaction from Children to Parents]”, Asahi Shimbun Digital, 12 February 2018).

Since the modification of the status of national universities into national university corporations in 2004, the amount of management expenses grants allotted for basic expenditure of those universities has significantly dropped (more than 100 billion yen from 2004 to 2016 according to a survey by the Ministry of Education and Science), placing the educational and research activities of the universities in jeopardy for reasons such as the increase of teaching staff on limited-term contracts (“Dodai-kara Kuzureyuku Nihon-no Kagaku, Hihei-suru Wakate Kenkyuushatachi, Korega Kagaku Gijutsu Rikkoku-no Ashimoto [Japan’s Science Crumbling from Its Foundation, Fatigued Young Researchers: This is the Bottom Line of the ‘Country Based on Science and Technology’]”, Wedge Infinity, 27 November 2017).

The problem is not limited to higher education. As the budget for education is so scarce and the personnel limited, it is reported that over half of the teachers in public elementary, junior high and high schools are working for long hours that exceed the threshold for risk of karoshi (death from overwork) (“Karoshi Lain Goe-no Kyouin, Kouritsuko-de Hansuu, Shigoto Mochikaeri-mo [Half of the Teachers in Public Schools are Working for Longer Hours than the Karoshi Line: Some Even Take Their Work Home]”, Asahi Shimbun Digital, 18 October 2018).

What will be the future of a country that does not devote money to education? In financial policies on how to spend taxpayers’ money, the realization of the right to education must be a matter of utmost priority.

5. Japan Violates the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Article 25 of the Japanese Constitution guarantees the right to subsistence. In addition, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Japan has ratified, recognizes the right to social security (Article 9) and the right to an adequate standard of living (Article 11, para.1), and obliges each State party to take steps to achieve these rights to the maximum of its available resources.

Given that State parties have recognized the rights guaranteed by this treaty and accepted their obligations to take steps for the realization of such rights, it would run counter to the object and purpose of the Covenant for a State party to take intentional retrogressive measures (the principle of non-retrogression). The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states, in its General Comment 3, that “any deliberately retrogressive measures … would require the most careful consideration and would need to be fully justified by reference to the totality of the rights provided for in the Covenant and in the context of the full use of the maximum available resources”.

In the light of such an understanding, the Committee, in its concluding observations to Japan in 2013, noted with concern that significant cuts to budget allocations for social assistance have negatively impacted the enjoyment of economic and social rights. The Committee also stated its concern that the average level of minimum wage in Japan falls short of the minimum subsistence level and the public assistance benefits, and that there is a growing rate of poverty among the elderly who have no or low-level pensions benefits (UN Doc. E/C.12/JPN/CO/3, paras.9, 18 and 22).

In May this year, four mandate holders in the UN Human Rights Council, including the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and the Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, adopted a joint statement sent to the Japanese government which declared that the cuts to livelihood assistance to be introduced from October violate Japan’s obligations under international human rights law. “In an affluent, developed country like Japan, these measures reflect a conscious political decision which directly undermines the rights of the poor to live with dignity”. “Austerity measures of this nature, adopted without careful consideration of their impact on the human rights of the poor, are in violation of Japan’s international obligations”.

The Covenant also recognizes the right to education, and states with regard to secondary and higher education that it shall be made generally available and accessible to all by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education. It also stipulates that an adequate fellowship system shall be established (Article 13, para.2). However, the meagerness of Japan’s public expenditure on education does not comply with these commitments.

************************************

Constraining the national budget by purchasing an exorbitant amount of weapons, including those charged to subsequent fiscal years, while cutting down public assistance benefits without proper examination and neglecting or even reducing the completely inadequate public expenditure on education, is contrary to the principles of pacifism, human rights protection and fiscal democracy in the Constitution as well as international legal obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (and other human rights instruments with similar obligations, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities).

We hereby strongly protest against the abnormal use of the defense budget under the Abe administration, and urge the government to allocate adequate funds to the areas of education and social security.

以上 総計233名(12月19日現在)

兵器に過度に偏重した国家運営は、このような学生たちの学ぶ権利も侵害する。

防衛費の膨大な増加に抗議し、教育と社会保障への優先的な公的支出を求める声明

2018年12月20日 研究者・実務家有志一同

声明の趣旨

世界的にも最悪の水準の債務を抱える中、巨額の兵器購入を続け、他方では生活保護や年金を引き下げ教育への公的支出を怠る日本政府の政策は、憲法と国際人権法に違反し、早急に是正されるべきである。

1.安倍政権は一般予算で史上最高規模の防衛予算を支出しているだけでなく、補填として補正予算も使い、しかも後年度予算(ローン)で米国から巨額の兵器を購入しており、これは日本国憲法の財政民主主義に反する。

2.米国の対日貿易赤字削減をも目的とした米国からの兵器「爆買い」で、国際的にも最悪の状態にある我が国の財政赤字はさらにひっ迫している。

3.他方で、生活保護費や年金の相次ぐ切り下げなど、福祉予算の大幅削減により、国民生活は圧迫され貧困が広がっている。

4.また、学生が多額の借金を負う奨学金問題や大学交付金削減に象徴されるように、我が国の教育予算は先進国の中でも最も貧弱なままである。

5.このように福祉を切り捨て教育予算を削減する一方で、巨額の予算を兵器購入に充てる政策は、憲法の社会権規定に反するだけでなく、国際人権社会権規約にも反する。

以下、具体的に理由を述べる。

1 膨大な防衛費増加と予算の使い込み

現在、安倍政権の下で防衛費は顕著に増加し続け(2013年度から6年連続増加)、2016年度予算からは、本予算単独でも5兆円を突破している。加えて、防衛省は、本来は自然災害や不況対策などに使われる補正予算を、本予算だけでは賄いきれない高額な米国製兵器購入の抜け道に使い、2014年度以降は毎年2,000億円前後の補正予算を計上して、戦闘機や輸送機オスプレイ、ミサイルなどを、米側の提示する法外な価格で購入している。

しかも、これには後年度負担つまり次年度以降へのつけ回しの「ローン」で買っているものが含まれ、国産兵器購入の分も合わせると、国が抱えている兵器ローンの残高は2018年度予算で約5兆800億円と、防衛予算そのものに匹敵する額に膨れ上がっている(2019年度は5兆3,000億円)。米国へのローン支払いが嵩む結果、防衛省が国内の防衛企業に対する装備品代金の支払いの延期を要請するという異例の事態まで起きている(「兵器ローン残高5兆円突破」「兵器予算 補正で穴埋め 兵器購入『第二の財布』」「膨らむ予算『裏技』駆使」「防衛省 支払い延期要請 防衛業界 戸惑い、反発」東京新聞2018年10月29日、11月1日、24日、29日記事参照)。毎会計年度の予算は国会の議決を経なければならないとしている財政民主主義の大原則(憲法86条)を空洞化する事態である。

防衛省の試算によれば、米国から購入し又は購入を予定している5種の兵器(戦闘機「F35」42機、オスプレイ17機、イージス・アショア2基など)だけで、廃棄までの20~30年間の維持整備費は2兆7,000億円を超える(「米製兵器維持費2兆7000億円」東京新聞11月2日)。一昨日、12月18日には政府は、今後5年間の「中期防衛力整備計画」(中期防)を決定し、過去最高となる27兆4,700億円もの防衛予算を盛り込んだ。戦闘機「F35」追加購入も、11月末には、1機100億円超のものを100機購入して計1兆円以上の見込みとされていた(2018年11月27日日本経済新聞)ものが、12月18日には、105機購入し総額は1兆2千億円以上の見込みと、金額がさらに膨れ上がっている(12月19日朝日新聞)。

2 米国のための高額兵器購入による財政逼迫

このような防衛費の異常な膨張について、根源的な問題の一つは、米国からの高額の兵器購入が、トランプ政権の要請も受け、米国の対日貿易赤字を解消する一助として行われていることである。

歳入のうち国債依存度が約35%を占め、国と地方の抱える長期債務残高が2018年度末で1,107兆円(対GDP比で約2倍の196%)に達するという、「主要先進国の中で最悪の水準」(財務省「日本の財政関係資料」2018年3月)の財政状況にある日本にとって、他国の赤字解消のために、さらなる借金を重ねてまで兵器購入に巨額の予算を費やすことは、国政の基盤をなす財政の運営として常軌を逸したものと言わざるを得ない。

また、導入されている兵器の中には、最新鋭ステルス戦闘機「F35」のような攻撃型兵器が多数含まれている。戦闘機が離着陸できるよう海上自衛隊の護衛艦「いずも」を事実上「空母化」することも、12月18日に閣議決定された新防衛大綱に含まれた。これらは、専守防衛の原則を逸脱する恐れがきわめて強い。

政府は北朝鮮情勢や中国の軍備増強を防衛力増強の理由として挙げるが、朝鮮半島ではむしろ緊張緩和の動きが活発化しているし、近隣国を仮想敵国として際限なく軍拡に走ることも、武力による威嚇を禁じ紛争の平和的解決を旨とする現代の国際法の大原則に合致せず、それ自体が近隣国の警戒感を高める、かえって危険な政策というべきである。

3 福祉切り捨ての現状

このように防衛費が破格の扱いで膨張する一方、政府は、生活保護費や年金の受給額を相次いで引き下げている。

生活保護については、2013年からの大幅引き下げに続き、今年10月からは新たに、食費など生活費にあてる生活扶助を最大で5%、3年間かけて引き下げることとされ、これにより、生活保護世帯の約7割の生活扶助費が減額となる。

しかし、削減にあたっては、減額された保護費が最低限の生活保障の基準を満たすのかどうかについての十分な検討がされておらず、厚生労働省の生活保護基準部会の報告書がこの点で提起した疑問は反映されていない。特に大きな影響を受ける母子世帯や高齢者世帯を含め、受給当事者の意見を聴取することも一切されていない。

生活保護基準は、最低賃金や住民税非課税限度額など様々な制度の基準になっているため、引き下げによる国民生活への悪影響は多方面にわたる。

また、年金については、2013年からの老齢基礎年金・厚生年金支給額の減額に続き、長期にわたり自動的に支給額が削減される「マクロ経済スライド」が2015年から発動されており、高齢者世帯の貧困状況は悪化している。

政府は生活保護減額によって160億円の予算削減を見込んでいるが、そもそも、国家財政を全体としてみた場合、この削減は、青天井に増加している防衛費の増加、とりわけ米国からの野放図な兵器購入を抑えれば、全く必要がなかったものである。

日本の国家財政は、米国の兵器産業における雇用の創出と維持のために用いられるべきものではない。国民の生存権よりも同盟国からの兵器購入を優先するような財政運営は根本的に間違っている。

4 主要国で最も貧弱な日本の教育予算

日本は、GDPに占める教育への公的支出割合が、主要国の中で例年最下位である。特に、日本は「高等教育の授業料が、データのあるOECD加盟国の中で最も高い国の一つであり、過去10年、授業料は上がり続けている」。「高等教育機関は多くを私費負担に頼っている。日本では、高等教育段階では68%の支出が家計によって負担されており、この割合は、OECD加盟国平均30%の2倍を超える」(OECD, Education at a Glance 2018)。

給付型奨学金は2017年にようやく導入されたものの、対象は住民税非課税世帯に限られ、学生数は各学年わずか2万人、給付額は月2~4万円にすぎない。大学生の約75%は私立大学で学んでいるが、国の私学助成が少ないため家計の負担が大きいところ、私大新入生のうち無利子奨学金を借りられるのは15%にすぎず(東京私大教連調査)、多くの卒業生は奨学金という名のローン返済に苦しんでいる。「卒業時に抱える平均負債額は32,170ドルで、返済には学士課程の学生で最大15年を要する。これは、データのあるOECD加盟国の中で最も多い負債の一つである」(OECD, supra)。2011年から2016年の5年間で延べ15,338人が、奨学金にからんで自己破産している(「奨学金破産、過去5年で延べ1万5千人 親子連鎖広がる」朝日新聞デジタル2018年2月12日)。

国立大学法人化後、その基盤経費となる運営費交付金も年々削減され(2004年から2016年までで実質1,000億円以上。文部科学省調査)、任期付き教員の増加など大学の教育・研究に支障をきたしている(「土台から崩れゆく日本の科学、疲弊する若手研究者たち これが『科学技術立国』の足元」Wedge Infinity 2017年11月27日)。

高等教育だけではない。教育予算が全体としてきわめて貧弱であり人員が少ないため、公立の小・中・高等学校では半数以上の教員が過労死レベルで働いている(「過労死ライン超えの教員、公立校で半数 仕事持ち帰りも」朝日新聞デジタル2018年10月18日)。

教育に予算を支出しない国に未来はあるだろうか。納税者から託された税金を何にどう用いるかという財政政策において、教育を受ける権利の実現は最優先事項の一つでなければならない。

5 日本は社会権規約に違反している

憲法25条は国民の生存権を保障している。また、日本が批准している「経済的、社会的及び文化的権利に関する国際規約」(社会権規約)は、社会保障についての権利(9条)、適切な生活水準についての権利(11条1項)を認め、国はこれらの権利の実現のために、利用可能な資源を最大限に用いて措置を取る義務があるとしている(2条1項)。

権利を認め、その実現に向けて措置を取る義務を負った以上は、権利の実現を後退させる措置を取ることは規約の趣旨に反する(後退禁止原則)。社会権規約委員会は「一般的意見」で、「いかなる意図的な後退的措置が取られる場合にも、国は、それがすべての選択肢を最大限慎重に検討した後に導入されたものであること、及び、国の利用可能な最大限の資源の完全な利用に照らして、規約に規定された権利全体との関連によってそれが正当化されること、を証明する責任を負う」としている。

このような観点から委員会は、日本に対する2013年の「総括所見」で、社会保障予算の大幅な削減に懸念を示している。また、日本の最低賃金の平均水準が最低生存水準及び生活保護水準を下回っていることや、無年金又は低年金の高齢者の間で貧困が広がっていることにも懸念を表明した(外務省ウェブサイト「国際人権規約」参照)。

今年(2018年)5月には、10月からの生活保護引き下げについて、「極度の貧困に関する特別報告者」を含む国連人権理事会の特別報告者ら4名が連名で、引き下げは日本の国際法上の義務に違反するという声明を発表し政府に送る事態となった。「日本のような豊かな先進国におけるこのような措置は、貧困層の人々が尊厳をもって生きる権利を直接に掘り崩す、意図的な政治的決定を反映している。」「貧困層の人権に与える影響を慎重に検討しないで取られたこのような緊縮措置は、日本が国際的に負っている義務に違反している」。

また社会権規約は、国はすべての者に教育の権利を認め、中等教育と高等教育については、無償教育を漸進的に導入することにより、すべての人に均等に機会が与えられるようにすることと規定している。適切な奨学金制度を設立することも定めている(13条2項)。教育に対する日本の公的支出の貧弱さはこれらを遵守したものになっていない。なお政府は2017年12月に閣議決定した「新しい政策パッケージ」で「高等教育の無償化」を打ち出したが、対象となる大学を選別する不当な要件を付しており問題が大きい。

**************************

後年度負担まで組んで莫大な額の兵器を買い込み国家財政を逼迫させる一方で、十分な検討も経ずに生活保護を引き下げることや、きわめて貧弱な教育予算を放置し又は削減することは、憲法の平和主義、人権保障及び財政上の原則のみならず、国際法上の義務である社会権規約(及び、同様の規定をもつ子どもの権利条約や障害者権利条約など)に違反している。我々は、安倍政権による防衛予算の異常な運営に抗議し反対の意を表明するとともに、教育と社会保障の分野に適切に予算を振り向けることを強く求めるものである。

<呼びかけ人>(五十音順、*発起人)

荒牧 重人(山梨学院大学教授、憲法学・子ども法)

井上 英夫(金沢大学名誉教授・佛教大学客員教授、人権論・社会保障法学)

大久保 賢一(弁護士、日本反核法律家協会事務局長)

小久保 哲郎(弁護士、生活保護問題対策全国会議事務局長)

今野 久子(弁護士)

澤藤 統一郎(弁護士、日本民主法律家協会元事務局長・日本弁護士連合会元消費者委員会委員長)

*申 惠丰(青山学院大学教授、国際人権法学会前理事長、国際人権法学)

田中 俊(弁護士)

谷口 真由美(大阪国際大学准教授、国際人権法学)

角田 由紀子(弁護士)

*徳岡 宏一朗(弁護士、日本反核法律家協会理事)

戸室 健作(千葉商科大学専任講師、社会政策論)

根森 健(神奈川大学特任教授、新潟大学・埼玉大学名誉教授、憲法学)

浜 矩子(同志社大学教授、経済学)

尾藤 廣喜(弁護士、生活保護問題対策全国会議代表幹事)

藤田 早苗(エセックス大学研究員、国際人権法学)

藤原 精吾(弁護士・日本反核法律家協会副会長・日本弁護士連合会元副会長)

吉田 雄大(弁護士)

以上 計18名

<賛同者>(五十音順)

青井 未帆(学習院大学教授、憲法学)

阿部 信行(白鴎大学法学部教授、法哲学・総合人間学)

浅倉 むつ子(早稲田大学教授、労働法学)

浅見 輝男(茨城大学名誉教授、土壌学)

麻生 多聞(鳴門教育大学准教授、憲法学)

阿部 浩己(明治学院大学教授、国際人権法学会元理事長、国際人権法学)

五十嵐 二葉(弁護士)

池内 了(名古屋大学名誉教授、宇宙物理学)

石井 まこと(大分大学教授、社会政策)

石塚 伸一(龍谷大学教授、刑事法学)

石川 裕一郎(聖学院大学教授、憲法学)

石口 俊一(弁護士)

市川 須美子(獨協大学教授、教育法学)

伊藤 周平(鹿児島大学教授、社会保障法学)

伊藤 真(伊藤塾塾長、弁護士)

伊藤 誠(東京大学名誉教授、経済学)

伊藤 芳朗(弁護士)

稲 正樹(国際基督教大学元教授、憲法学)

井上 啓(弁護士)

井上 幸夫(弁護士)

井口 克郎(神戸大学准教授、社会保障・経済学)

井原 聰(東北大学名誉教授、科学史・技術史)

今井 直(宇都宮大学名誉教授、国際人権法学)

今泉 義竜(弁護士)

今川 正章(弁護士)

岩井 信(弁護士)

岩崎 晋也(法政大学教授、社会福祉学)

上西 充子(法政大学教授、労働問題)

上野 千鶴子(東京大学名誉教授、社会学)

上柳 敏郎(弁護士)

内田 樹(神戸女学院大学名誉教授、哲学)

内田 博文(九州大学名誉教授、刑事法学)

梅田 康夫(元金沢大学教授、日本法制史)

浦田 賢治(早稲田大学名誉教授、憲法学)

江夏 大樹(弁護士)

江森 民夫(弁護士)

大久保 佐和子(弁護士)

大竹 寿幸(弁護士)

大西連(NPO法人「もやい」理事長)

大藤 紀子(獨協大学教授、憲法学)

岡崎 敬(弁護士・伊藤塾講師)

岡田 正則(早稲田大学教授、行政法学)

岡田 行雄(熊本大学教授、刑事法学)

岡野 八代(同志社大学教授、政治思想・フェミニズム思想)

小川 隆太郎(弁護士)

小木 和夫(弁護士)

尾﨑 恭一(東京薬科大学客員教授、医療倫理・哲学)

小沢 隆一(東京慈恵会医科大学教授、憲法学)

戒能 通厚(名古屋大学・早稲田大学名誉教授、法学)

垣内 国光(明星大学名誉教授、子ども家庭福祉論)

覚正 豊和 (敬愛大学教授、 刑事法学)

嘉指 信雄(神戸大学教授、哲学)

笠松 健一(弁護士)

加藤 健次(弁護士)

加藤 節(成蹊大学名誉教授、政治哲学)

金子 匡良(法政大学教授、憲法学)

上条 貞夫((弁護士)

上脇 博之(神戸学院大学教授、憲法学)

川口 智也(弁護士)

川島 聡(岡山理科大学准教授、国際人権法学・障害法学)

河合 正雄(弘前大学講師、憲法学)

菊地 洋(岩手大学准教授、憲法学)

岸 朋弘(弁護士)

木島 紗千恵(弁護士)

北見 秀司(津田塾大学教授、哲学・社会思想史)

北村 泰三(中央大学教授、国際法学)

北澤 貞男(弁護士)

君和田 伸仁(弁護士)

木村 康則(弁護士)

清末 愛砂(室蘭工業大学大学院准教授、憲法学)

草場 裕之(弁護士)

楠 晋一(弁護士)

葛野 尋之(一橋大学教授、刑事法学)

楠本 敏行(弁護士)

窪 誠(大阪産業大学教授、国際法学)

黒岩 哲彦(弁護士)

合田 公計(大分大学名誉教授、経済学)

河野 善一郎(弁護士)

伍賀 一道(金沢大学名誉教授、社会政策)

小部 正治(弁護士)

後藤 弘子(千葉大学教授、刑事法学)

児玉 勇二(弁護士)

後藤 道夫(都留文科大学名誉教授、社会哲学・現代社会論)

小林 譲二(弁護士、早稲田大学大学院教授)

小林 節(慶應義塾大学名誉教授、憲法学)

小林 武(沖縄大学客員教授、憲法学)

駒井 重忠(弁護士、鳥取県弁護士会会長)

小森 陽一(東京大学教授、日本近代文学)

小森田 秋夫(神奈川大学教授、比較法学)

齊藤 純一(早稲田大学教授、政治学)

坂本 修(弁護士)

坂本 雅弥(弁護士)

佐々木 光明(神戸学院大学教授、刑事法学・少年司法)

笹沼 弘志(静岡大学教授、憲法学・生活保護法学)

佐藤 潤一(大阪産業大学教授、憲法学)

佐藤 博文(弁護士)

佐藤 学(学習院大学特任教授、教育学)

佐藤 安信(東京大学教授、人間の安全保障)

佐藤 由紀子(弁護士)

志田 陽子(武蔵野美術大学教授、憲法学)

芝池 俊輝(弁護士)

芝田 英昭(立教大学教授、社会保障論)

清水 雅彦(日本体育大学教授、憲法学)

島岡 まな(大阪大学法科大学院教授、刑法)

島袋 純(琉球大学教授、地方自治論・行政学)

志村 新(弁護士)

白井 邦彦(青山学院大学教授、労働経済学)

白藤 博行(専修大学教授、行政法)

須網 隆夫(早稲田大学教授、EU法学・国際経済法学)

菅 俊治(弁護士)

菅原 絵美(大阪経済法科大学准教授、国際人権法学)

菅原 真(南山大学教授、憲法学)

杉浦 ひとみ(弁護士)

鈴木 靜(愛媛大学教授、社会保障法学)

鈴木 亜英(弁護士)

鈴木 勉(佛教大学教授、福祉政策論)

鈴木 博人(中央大学法学部教授、家族法)

青龍 美和子(弁護士)

芹澤 齊(青山学院大学名誉教授、憲法学)

曽我 千春(金沢星稜大学教授、社会保障・社会福祉政策)

空野 佳弘(弁護士)

髙木 和美(岐阜大学教授、社会福祉学、労働・生活問題)

高木 博史(岐阜経済大学教授、社会福祉学)

髙崎 暢(弁護士)

高田 清恵(琉球大学教授、社会保障法学)

高橋 哲哉(東京大学教授、哲学)

髙山 佳奈子(京都大学教授、刑事法学)

滝沢 香(弁護士)

武井 寛(甲南大学教授、労働法)

武村 二三夫(弁護士)

建石 真公子(法政大学教授、憲法学)

田中 明彦(龍谷大学教授、社会保障法学)

谷口 洋幸(金沢大学准教授、国際人権法学・ジェンダー法学)

千葉 眞(国際基督教大学特任教授、政治思想)

津田 玄児(弁護士)

土屋 仁美(金沢星稜大学講師、憲法学)

坪井 節子(弁護士)

寺中 誠(東京経済大学講師、人権論・刑事政策論)

登坂 真人(弁護士)

中川 明(弁護士)

中川 勝之(弁護士)

中川 武夫(中京大学名誉教授、公衆衛生学)

中塚 明(奈良女子大学名誉教授、日本近代史)

中谷 雄二(弁護士)

長友 薫輝(三重短期大学教授、社会保障論)

中野 晃一(上智大学教授、政治学)

中森 俊久(弁護士)

並木 陽介(弁護士)

新倉 修(青山学院大学名誉教授、刑事法学、弁護士)

成嶋 隆(獨協大学教授、憲法学)

新井田 智幸(東京経済大学専任講師、経済思想)

丹生 淳郷(日本科学者会議埼玉支部事務局長、薬学)

西海 真樹(中央大学教授、国際法学)

西崎 文子(東京大学教授、歴史学)

西谷 修(立教大学特任教授、哲学・思想史)

西山 明行(弁護士・日本反核法律家協会理事)

二宮 孝富(大分大学名誉教授、民法学・法社会学)

野澤 裕昭(弁護士)

橋本 佳子(弁護士)

長谷川 悠美(弁護士)

原口 暁美(弁護士)

林 治(弁護士)

半田 久之(司法書士)

秀嶋 ゆかり(弁護士)

平井 康太(弁護士)

平井 哲史(弁護士)

広瀬 訓(長崎大学教授、国際法学)

藤岡 毅(弁護士)

渕上 隆(弁護士)

淵脇 みどり(弁護士)

古橋 エツ子(花園大学名誉教授、社会保障法学)

星野 圭(弁護士)

堀尾 輝久(東京大学名誉教授、教育学)

本庄 十喜(北海道教育大学准教授、日本史)

本田 伊孝(弁護士)

本間 照光(青山学院大学名誉教授、保険論・社会保障論)

牧野 忠康(日本福祉大学名誉教授、保健学)

正木 みどり(弁護士)

益川 敏英(京都大学名誉教授、物理学/ノーベル賞受賞者)

松下 一世(佐賀大学教授、教育学・人権教育学)

松村 高夫(慶應義塾大学名誉教授、社会史)

松山 秀樹(弁護士)

間宮 陽介(青山学院大学特任教授、経済学)

三浦 永光(津田塾大学名誉教授、哲学・社会思想史)

三上 昭彦(明治大学元教授、教育学)

三島 憲一(大阪大学名誉教授、哲学・思想史)

水島 朝穂(早稲田大学教授、憲法学)

水野 和夫(法政大学教授、経済学)

水口 洋介(弁護士)

簑田 孝行(弁護士)

宮本 憲一(大阪市立大学名誉教授、経済学)

武藤 達夫(関東学院大学准教授、国際法学・国際人権法学)

村井 敏邦(一橋大学・龍谷大学名誉教授・弁護士、刑事法学)

村山 裕(弁護士)

元 百合子(大阪経済法科大学客員研究員・大阪女学院大学元教授、国際人権法学)

望月 彰(名古屋経済大学教授、教育学)

本 秀紀(名古屋大学教授、憲法学)

安原 陽平(沖縄国際大学講師、憲法学・教育法学)

柳澤 繁孝(大分大学名誉教授、口腔外科学)

山田 麻紗子(人間環境大学特任教授、司法・犯罪心理学)

山田 由紀子(弁護士)

山本 忠(立命館大学教授、社会保障法学)

雪田 樹理(弁護士)

横湯 園子(中央大学元教授、臨床心理学)

吉田 裕(一橋大学特任教授、日本史)

世取山 洋介(新潟大学教授、教育法学)

脇田 滋(龍谷大学名誉教授、労働法・社会保障法学)

鷲谷 いづみ(中央大学教授、保全生態学)

鷲谷 徹(中央大学教授、経済政策)

渡辺 治(一橋大学名誉教授、政治学・憲法学)

和田 肇(名古屋大学教授、労働法学)

以上 計 209名

【研究者・法曹実務家以外の賛同者】

赤羽根 巖(医師)

莇 昭三(医師、全日本民医連名誉会長)

武田 さち子(一般社団法人ここから未来 理事、教育評論)

藤野 興一(前全国児童養護施設協議会会長・子どもの虐待防止ネットワーク鳥取理事、ソーシャルワーカー)

松本 文六(医師)

みわよしこ(フリーライター)

横川 和夫(ジャーナリスト)

Statement of Protest against the Massive Increase of the Defense Budget: An Urgent Call for Prioritized Public Expenditure on Education and Social Security

[Full text with citations; For distribution in the press conference]

Group of Scholars and Lawyers, 20 December 2018

The Japanese government’s policy of continuing to purchase an exorbitant amount of weapons in order to reduce the trade deficit of the US with Japan, in spite of the fact that Japan has the highest national debt in the world, while cutting social security benefits and neglecting public expenditure on education, is contrary to the Constitution as well as international human rights law, and thus needs to be urgently corrected.

Summary:

1. The Abe administration is not only spending an unprecedented amount on defense under the main budget, but has also resorted to the supplementary national budget to buy an exorbitant number of weapons from the US on loan. This is contrary to the principle of fiscal democracy in the Japanese Constitution.

2. As a consequence of this massive purchase of weapons from the US, designed partly to reduce the US trade deficit with Japan, the fiscal condition of Japan, which has the worst national debt in the world, has become even more constrained.

3. On the other hand, the social security budget has been greatly reduced in recent years, with continuing cuts being made to public assistance benefits and pension benefits, widening the spread of poverty of citizens.

4. In addition, the amount spent on education as a percentage of GDP remains the lowest among industrialized countries, a situation exemplified by the problem of student loans (“scholarships”) and the reduction of management expenses grants to national universities.

5. The government’s policy of allocating massive amounts of money for the purchase of weapons, while cutting down on social security and reducing the education budget, not only runs counter to the social rights provisions in the Constitution but also the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

These five points are explained in greater detail below.

1. Massive Increase in Defense Expenditure and Abusive Use of the National Budget

Under the Abe administration, the defense budget has continued to rise steeply (for six years in a row since 2013), and since fiscal year 2016, it has exceeded 5 trillion yen ($ 44 billion) under the main budget alone. In addition, the Ministry of Defense has resorted to the supplementary national budget, designed originally to be used for natural disasters and measures in response to economic depression, as a loophole to buy expensive US weapons that the main budget cannot cover. Since 2014, the Ministry has piled up supplementary budget requests of approximately 200 billion yen ($ 17.6 billion) each year, and has purchased fighter planes, Ospreys and missiles at an exorbitant price presented by the US.

Furthermore, these purchases include those charged to subsequent years, i.e. made “on loan”. Combined with the purchase of domestic defense products, the bill for loans for weapons charged to the government amounts to 5.08 trillion yen ($ 44.7 billion) for fiscal year 2018 (5.3 trillion yen for 2019), equal to the whole defense budget for the year. This situation seriously undermines the basic principle by which the budget for every fiscal year must be approved by the Diet (Article 86 of the Constitution).

As a consequence of costly payment of loans to the US, an unprecedented situation occurred recently: the Ministry of Defense requested the deferral of payment for defense products from domestic defense industries (see articles in the Tokyo Shimbun, “Heiki Loun Zandaka Go Cho-en Toppa [the Bill for Weapon Loan Exceeds 5 Trillion Yen]”, “Heiki Yosan Hosei-de Anaume: Heiki Kounyu Daini-no Saifu [Filling up the Spending on Weapons with Supplementary Budget: ‘Second Wallet’ for Weapons]”, “Fukuramu Yosan: ‘Urawaza’ Kushi [Mushrooming Budget: Use of a ‘Trick’]”, “Boueisho Shiharai Enki Yousei: Bouei Gyokai Tomadoi Hampatsu [The Ministry of Defense Asks for Deferral of Payment: Embarrassment and Resistance of Defense Industries], 29 October, 1, 24 and 29 November 2018).

According to a calculation by the Ministry of Defense, the cost of maintenance and support for five kinds of weapons purchased or to be purchased from the US (such as forty-two “F35” fighter planes, seventeen Ospreys, and two sets of the Aegis Ashore missile defense system) over twenty to thirty years of usage before being discarded will exceed 2.7 trillion yen ($ 238 billion) (Tokyo Shimbun, 2 November 2018). On top of that, the government is considering an additional purchase of a maximum of 100 F35 stealth fighter planes at a cost of over 10 billion yen each, totaling over 1 trillion yen ($ 8.8 billion) (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 27 November 2018). On December 18th, the government approved the new five-year defense plan assuming record spending of 27.47 trillion yen ($ 242 billion). It was also announced that the number of F35 fighter planes to be purchased would be 105, with the total amount swelling to at least 1.2 trillion yen ($ 8.9 billion) (Asahi Shimbun, 18 December 2018).

2. Constraint on the National Budget Due to the Purchase of Expensive Weapons for the Sake of the US

One of the fundamental questions posed by such an abnormal increase in defense expenditure is that the purchase of expensive weapons from the US is conducted, under pressure from the Trump Administration, as a means of alleviating the U.S. trade deficit with Japan.

As the Ministry of Finance admits (the Ministry of Finance, “Nihon-no Zaisei Kankei Shiryo [Materials Concerning Japan’s Finance]”, March 2018), the financial situation of Japan is “at the worst level among major industrialized countries”, with the amount of long-term debt reaching 1.1 trillion yen ($ 9.7 billion) at the end of fiscal year 2018 (196 percent of the national GDP). Under such conditions, it is totally unacceptable, in terms of administration of the national budget, which represents essential resources for public policies, to spend such a large amount of public money on armaments and increase the national debt even further.

It is to be noted that the weapons thus purchased include numerous products, such as cutting-edge F35 stealth fighter planes, that are utilized for attacks rather than defense. The government also approved transforming the escort ships “Izumo” of the Self Defense Force into an aircraft carrier so that fighter planes may take off and land. There is a serious concern that the use of these armaments will deviate from the principle of self-defense adhered to by previous administrations.

While the government invokes the situation related to North Korea and China’s extension of its military power as justifications for increased defense expenditure, we are, as a matter of fact, witnessing an active movement towards détente on the Korean Peninsula. Resorting to unlimited expansion of military power, assuming that neighboring countries are virtual enemy States, is not consistent with the basic principles of international law prohibiting the threat of force and obliging peaceful settlement of disputes. It is also a dangerous policy in itself that aggravates the sense of wariness held by those countries.

3. Reduction of Social Security Benefits by the Government

At the same time that it is expanding the defense budget to an exceptional degree, the government has also sharply cut down social security benefits one after another.

As regards public assistance, the last safety net for the right to subsistence, it has been decided that the amount of livelihood assistance intended for food and other basic living expenses is to be lowered by a maximum of five percent for the next three years starting from October this year.

However, this cut was carried out without reflecting on those voices questioning whether the reduced amount would meet the minimum level of social protection raised in the reports of the Committee on the Standard of Public Assistance under the Ministry of Welfare and Labor. A process of public consultation for those concerned, including most-affected households such as single-mother households and households of the elderly, was also nonexistent.

As the standard of public assistance benefits is used as a standard in other systems, such as the minimum wage and exemption from the payment of resident tax, a lowering of this standard has a negative impact on the general population in many ways.

As regards pension benefits, following the cuts to the basic old-age pension as well as the employee pension in 2013, a “macro-economic slide” mechanism, which will automatically keep increases in pension benefits below the rate of inflation over the long term, has been implemented since 2015, aggravating the poverty of the elderly.

The government intends to make a budgetary cut of 16 billion yen ($ 140 million) by reducing expenditure on public assistance from this year. However, if we take the national budget as a whole, this measure was far from necessary in light of the sharp rise in defense expenditure, particularly the reckless purchase of expensive weapons from the US.

The national budget of Japan is not to be used for the creation and maintenance of employment in the defense industry of the US. Administering the national budget in a way that prioritizes the purchase of weapons from an ally over the right to subsistence of citizens is fundamentally wrong and unjustifiable.

4. Japan’s Most Inadequate Public Expenditure on Education

Japan ranks the lowest among the major industrialized countries in terms of its public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP. In particular, “Japan has some of the highest tertiary tuition fees among OECD countries with available data, and they have been increasing in the past decade”. “Tertiary educational institutions… rely heavily on private funding: 68 percent of the expenditure is privately funded at this level in Japan, over twice the OECD average of 30%” (OECD, Education at a Glance 2018).

Although a grant-type scholarship was belatedly introduced in 2017, only those who live in households with the lowest income, exempt from the payment of resident tax, are eligible. Barely 20,000 students are chosen among them, and the amount given is only 20,000 to 40,000 yen per month. While nearly 75 percent of university students are enrolled in private universities, only a handful of freshmen (15 percent) may avail themselves of loan-type but interest-free “scholarships”. Many graduates and their families are plagued with the reimbursement of such loans in the name of “scholarships”. “The average debt on graduation is $ 32,170 and repayment can take up to 15 years for students graduating with a bachelor’s degree, one of the highest debt burdens on tertiary graduates across OECD countries with available data” (OECD, supra). A total of 15,338 people were compelled to file for bankruptcy deriving from the problem of “scholarship” between 2011 and 2016 (“Shogakukin Hasan, Kako Gonen-de Nobe Ichiman Gosen-nin: Oyako Rensa HIrogaru [A Total of 15,338 People Went Bankrupt Due to Scholarship: Spread of Chain Reaction from Children to Parents]”, Asahi Shimbun Digital, 12 February 2018).

Since the modification of the status of national universities into national university corporations in 2004, the amount of management expenses grants allotted for basic expenditure of those universities has significantly dropped (more than 100 billion yen from 2004 to 2016 according to a survey by the Ministry of Education and Science), placing the educational and research activities of the universities in jeopardy for reasons such as the increase of teaching staff on limited-term contracts (“Dodai-kara Kuzureyuku Nihon-no Kagaku, Hihei-suru Wakate Kenkyuushatachi, Korega Kagaku Gijutsu Rikkoku-no Ashimoto [Japan’s Science Crumbling from Its Foundation, Fatigued Young Researchers: This is the Bottom Line of the ‘Country Based on Science and Technology’]”, Wedge Infinity, 27 November 2017).

The problem is not limited to higher education. As the budget for education is so scarce and the personnel limited, it is reported that over half of the teachers in public elementary, junior high and high schools are working for long hours that exceed the threshold for risk of karoshi (death from overwork) (“Karoshi Lain Goe-no Kyouin, Kouritsuko-de Hansuu, Shigoto Mochikaeri-mo [Half of the Teachers in Public Schools are Working for Longer Hours than the Karoshi Line: Some Even Take Their Work Home]”, Asahi Shimbun Digital, 18 October 2018).

What will be the future of a country that does not devote money to education? In financial policies on how to spend taxpayers’ money, the realization of the right to education must be a matter of utmost priority.

5. Japan Violates the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Article 25 of the Japanese Constitution guarantees the right to subsistence. In addition, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Japan has ratified, recognizes the right to social security (Article 9) and the right to an adequate standard of living (Article 11, para.1), and obliges each State party to take steps to achieve these rights to the maximum of its available resources.

Given that State parties have recognized the rights guaranteed by this treaty and accepted their obligations to take steps for the realization of such rights, it would run counter to the object and purpose of the Covenant for a State party to take intentional retrogressive measures (the principle of non-retrogression). The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states, in its General Comment 3, that “any deliberately retrogressive measures … would require the most careful consideration and would need to be fully justified by reference to the totality of the rights provided for in the Covenant and in the context of the full use of the maximum available resources”.

In the light of such an understanding, the Committee, in its concluding observations to Japan in 2013, noted with concern that significant cuts to budget allocations for social assistance have negatively impacted the enjoyment of economic and social rights. The Committee also stated its concern that the average level of minimum wage in Japan falls short of the minimum subsistence level and the public assistance benefits, and that there is a growing rate of poverty among the elderly who have no or low-level pensions benefits (UN Doc. E/C.12/JPN/CO/3, paras.9, 18 and 22).

In May this year, four mandate holders in the UN Human Rights Council, including the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and the Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, adopted a joint statement sent to the Japanese government which declared that the cuts to livelihood assistance to be introduced from October violate Japan’s obligations under international human rights law. “In an affluent, developed country like Japan, these measures reflect a conscious political decision which directly undermines the rights of the poor to live with dignity”. “Austerity measures of this nature, adopted without careful consideration of their impact on the human rights of the poor, are in violation of Japan’s international obligations”.

The Covenant also recognizes the right to education, and states with regard to secondary and higher education that it shall be made generally available and accessible to all by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education. It also stipulates that an adequate fellowship system shall be established (Article 13, para.2). However, the meagerness of Japan’s public expenditure on education does not comply with these commitments.

************************************

Constraining the national budget by purchasing an exorbitant amount of weapons, including those charged to subsequent fiscal years, while cutting down public assistance benefits without proper examination and neglecting or even reducing the completely inadequate public expenditure on education, is contrary to the principles of pacifism, human rights protection and fiscal democracy in the Constitution as well as international legal obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (and other human rights instruments with similar obligations, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities).

We hereby strongly protest against the abnormal use of the defense budget under the Abe administration, and urge the government to allocate adequate funds to the areas of education and social security.

以上 総計233名(12月19日現在)