ミラーニューロン - 考えかたは100%他人の影響 - 02 - 1

前の内容:

ミラーニューロン - 考えかたは100%他人の影響 - 01

(2015-02-22 07:07:18 | 心を掘り下げる(内観))

マイナスのミラーニューロンの影響をなくして、

ポジティブなミラーニューロンの影響を増やす。

長期的に総合的にみて、幸せな人をメンターに選ぶ。

どうすれば、さらにこの人たち(メンター)に提供できるかと考える。

以心伝心(天網恢々疎にして漏らさず)

良いものを取り入れることに集中する。

尊敬できる人と一秒でも多くいるように考える。

一人一人を大事にする。

ポジティブなミラーニューロンの人を増やしていく。

長期的に総合的にみて、誰かを幸せにすると、幸せの連鎖が広がる。

ポジティブな環境(個人・グループ)を自分でつくる。

参考サイト:

誰かと同じ現実を持つと、その人と同じ結果を持つことになる。

(2015-02-26 21:58:30 | 心を掘り下げる(内観))

六つのステップ

六つのステップは、セドナメソッドのエッセンスの精髄です。1974年にレスター・レヴェンソンが、解放の全手順を要約するために作りました。

Lester Levenson - the true story (英語です。)

http://www.presentlove.com/lester-levenson/

Lester Levenson’s story

In the hospital.

Lester Levenson

At the end of two weeks, Dr. Schultz arrived for his regular morning visit, and after examining his patient, pulled up a chair and sat down. “I’m discharging you today. Your condition is stable, and there’s no reason to keep you here any longer. Now that doesn’t mean you’re well. Far from it. You need an indefinite period of convalescence as well as checkups at regular intervals. But you don’t need to be in the hospital any longer. You can continue with bed rest and medication at home.” The doctor went on to outline his at-home program of rest, medication, and regular office visits; his diet; social activities (none); even his sex life (also none). Lester was surprised, but determined to follow doctor’s orders. “How long will this go on, Doc?” he asked. “How long do I have to take it easy like this? I realize you can’t tell me exactly, but can you give me some idea?” He watched the doctor carefully as he waited for an answer. It seemed like a long time before Dr. Schultz spoke. “How old are you, son?” That wasn’t what he expected. He wondered what was coming next. There was something in the doctor’s manner he didn’t like. “Forty-two,” he answered and waited. Dr. Schultz looked out the window, his face impassive as he sat lost in thought. After a long moment, during which neither man moved, the doctor nodded his head once, a sharp decisive movement which frightened Lester, and spoke abruptly and with finality. “From now on, I’m afraid.”

“What do you mean, from now on?” A very sick feeling was rising from his gut, up into his stomach. “I mean that you cannot expect to live a normal life from here on.” He went on quickly when he saw Lester’s shocked look. “You’ve just had a very serious coronary; you’re lucky to be alive at all. Anyone else would have been dead by now with the severity of this attack.” The doctor paused, then cleared his throat, “I realize how difficult it must be for you to hear this, but I assure you it isn’t pleasant for me either.” He got up abruptly and walked to the window, his back to Lester. “I wish there were something else I could say; I wish I could tell you that in a few months you’d be back to normal and could pick up your life where you left off,” he paused, turning to face Lester quietly, “but I can’t. In all conscience, I can’t tell you that And I’m sorry.” Lester was angry now. “You’re sorry? Well, so am I! You saved my life … for what? So that I can be an invalid for the rest of it? What the hell kind of life are you giving me back anyway?” Once started, he couldn’t stop. He raved on and on. All his frustration, rage and anger poured out until the sick feeling in the pit of his stomach finally rose to his throat and he began to cough and choke. The doctor held a basin for him while he gagged and heaved and finally fell back exhausted onto the pillows, his hand shaking as he reached up to wipe his mouth. The doctor was shaking too as he carried the soiled basin to the bathroom. He carefully placed it on the floor, then hunched over the sink, one hand on each side of it supporting his weight, his forehead touching the cold mirror of the medicine chest on the wall. In spite of all his years of practice, these situations still affected him. He thought of home and wished he were there now, his day over, relaxing before dinner with a drink or two. With a deep sigh, he pulled himself erect and walked back into the room. “I’ll sign the discharge papers today. but you can stay on if you want,” he said quietly “If you need more time to make your arrangements, I’ll tell the nurse it’s okay.” He didn’t know what else to say. Lester answered, “No, that’s all right, I’ll leave today, this afternoon. There doesn’t seem to be any point in prolonging it” “All right, whatever you decide is all right. But remember that you can change your mind and stay a bit longer if you want.” He stood in silence for a moment, while he closely examined Lester’s ashen face. “Please be sure to take it easy when you get home. I can’t overemphasize the importance of that. You shouldn’t climb any stairs at all. And do you have shoes without laces; you know, loafers?” “Loafers? No, why?” “You might want to have someone buy you a pair. It’s better if you don’t have to bend over to tie your shoes. It puts an additional strain on your heart when you get into that position.” The idea struck Lester as ridiculous but all he said was “Okay, whatever you say.” He’d always hated loafers but it didn’t matter now. Then as he watched the doctor walk toward the door, a question occurred to him. “Doc,” he asked, “I’m not going to die, am I? I mean, I might have to kind of take it easy from here on, but I’m not going to die, right?” Dr. Schultz stopped. “I don’t know,” he answered, then turned to face Lester. “I wish I could give you a positive answer, but I can’t. The truth is that I simply don’t know. You’ve had a massive heart attack and you could live for another year or two, or you could go tomorrow. I just don’t know.” “Thanks for being honest with me, Doc. I’ll be seeing you.”

Lester goes home.

That afternoon, he went home to his penthouse as though to a tomb. “It is a tomb,” he thought, “and I’m a dead man. I guess I’ll just have to get used to it.” His sisters wanted to help and offered to take turns staying with him, to take care of him, but he sent them away. He just wanted to be by himself. He went to bed and mostly slept for three days, waking up only occasionally to eat, or take his medicines, or use the bathroom. Then he’d crawl, like a wounded animal, back to his hole. On the fourth day something changed. After his midday meal he was sitting in a chair, looking out the window at Central Park. There was snow; the trees were sparkling; the park looked like a fairyland. He was thinking of how beautiful it was and then realized that he wasn’t enjoying it at all. He could not respond, even to beauty. He was a virtual invalid, with no hope of ever getting any better. At best, he could look forward to years of sitting in this apartment, nursing a frail corpse that hadn’t the good sense to lie down and get it over with. That thought made him so furious he got up from his chair with the greatest surge of energy he’d had since his attack, went straight to the medicine chest in the bathroom and counted his pills. He found a good supply of the newer medications; sedatives and heart pills. There were also morphine tablets a doctor had prescribed some years before for the pain of kidney stones. There were certainly enough left in the bottle to take him off this planet if he chose to go. And morphine would be such a nice way to go; you just floated off on a warm, cozy cloud, everything rosy. It was certainly better than waiting for another heart attack. Okay. Now he had a choice. For the first time since his illness, he felt he had some control over what happened to him. He considered what to do. Should he take the pills now and get it over with? No, not right now he decided; he could always take them when and if things got too bad. He went back to his chair and began looking the situation over, speaking aloud to himself, “You’re still breathing. No matter what those doctors or anyone else says about the prognosis, you’re still breathing, and that’s what counts. Maybe there’s some hope after all.” “Okay, where do I start?” That question brought on the sinking feeling again, and it occurred to him that perhaps he should go ahead and take the pills at once. At least then he’d be out of his misery and could stop fighting. And what had he been fighting for all his life anyway? Just a little happiness, that was all; and he hadn’t found it, not ever, not in any way that lasted more than a few minutes or hours at a time. Momentary… that’s what life was… momentary… impermanent… always changing… you’d no sooner think you had it made, had everything nailed down and could relax, than the next thing would happen and there you were again … right back where you’d started … clutching, clutching, clutching for something you couldn’t hold even if you got it. What the hell was life all about anyway? What was it all about? What was he doing here on this planet? It didn’t make any sense to him that he should be born; go through all he had gone through in his life; never really get anywhere that really mattered; and end up with nothing, absolutely nothing except a dying body and eventually even that turns to dust. All his possessions and accomplishments felt meaningless and empty. “Like dust,” he thought. “Ashes to ashes and dust to dust… If the war doesn’t get you, the taxes must.” He had to laugh at the truth in that silly rhyme. Life seemed so stupid. But as he thought about taking the pills, he realized that he couldn’t give up yet. There was something stirring in the back of his mind … an elusive thought that there might be an answer if only he knew where to look. Well, he had nothing but time, he figured, and even though his body was half dead, he still had his mind; he could still think. “Should I try?” he wondered aloud. For a moment, he wavered, then decided with a shrug, “Oh, what the hell … I got nothing to lose. If it doesn’t work, I can always take the pills.” And he knew he would if it came to that. There was no doubt in his mind.

That being settled, he didn’t have to think about it again. His mind felt clearer than it had in a long time, and for the first time since his illness, he felt truly hungry. He went to the kitchen and fixed himself a real meal. Still very weak, he took his time and didn’t try to rush. As he ate, his mind was busy exploring new thoughts, questions, ideas of where to look for his answer. The new project was exciting and he felt himself coming alive again. Refreshed and strengthened by the meal, he went back to his chair by the window. “Where to begin?” he wondered, “Well, first, what are the questions?” What is life? What is it all about? Is there a reason for my being here in this world, and if so, what is it?” “What is life? What is it that I’ve been looking for?” “Just a little happiness, that’s all,” he answered himself. “Okay, then, what is happiness? How do you get it? Where do you find it?” “What is life? What is this world all about and what is my relationship to it?” “How did I get into this mess I’m in?” “Is there a way out of this mess?” He already knew the answer to that one. Other than dying, there is no way out, but he thought if he could only get the answers, at least he’d know the reason for his life. He might make some sense out of it all, and that would be something. It would have to do. First, he looked in the dictionary for definitions of happiness and life. They didn’t tell him anything he didn’t already know. Next, he went to his library of books collected over the years. There was Freud; could there be anything useful in that? No, he’d tried Freudian analysis for years, and it hadn’t helped. He’d also read every book Freud had written that had been translated into English and hadn’t found the answers. No, Freud had no answers for him. He went on to others; Watson’s Behaviorism, Jung and Adler, nothing for him in those, either. Then there were the philosophers. He began taking books from the shelves, putting them in a pile. He’d read them all cover to cover more than once, but maybe he’d missed something. After all, he thought, he hadn’t then had specific questions. Taking books to his chair by the window, he began to read. He skimmed through one after the other, stopping to read paragraphs or pages here and there. His head began to feel clogged with information, and his thoughts were spinning. More and more impatient, he went back to the shelves for other books, books on medicine, physics, engineering. He had books on everything and he looked through them all over the next two days. The room was a mess, books piled everywhere, some lying open on the floor where he had thrown them in his frustration. The only ones left on the shelves were a joke book and some biographies, which had been given to him as gifts. Where to look next? “You were always a smart boy” he told himself. “Didn’t you win a full scholarship to Rutgers by competitive exams when there were only three being given? Even though you were a Jew, they couldn’t hold that back from you. You won it! “And in school, weren’t you always on the honor roll? And haven’t you read tons of stuff on man, from engineering and physics to psychiatry and philosophy and medicine? “Well, if you’re so smart, big shot, what did all that study and knowledge and reading get you? Migraines, kidney stones, ulcers, appendicitis, pain, misery, unhappiness, and finally a coronary which should have finished you off and didn’t. What more do you need before you come to your senses? “For a smart boy Lester, you are stupid, stupid, stupid! All that knowledge has availed you nothing. And here you are looking for more, wanting more books written by someone else who hasn’t found the answers either.” “That’s that!” he told himself. “I’m finished with all that crap.” With that decision, he felt a lifetime burden lift from his shoulders. Suddenly he felt light, almost giddy. He realized he had actually been looking for the same answers all his life, but now he knew, without a doubt, that if they were to be found in any of the conventional places, he would have already found them. He would have to look somewhere else. And he thought he knew where. He would put all that useless knowledge aside, disregard everything he’d learned, go back to the lab and start from scratch. The problems were within him, he reasoned. It was his body, his mind, his emotions. The answers must be within him, too. That was his lab and that’s where he would look. It felt good. He went to his chair and began.

Answers begin to emerge.

For a month he sat, relentlessly questioning, probing. At first, he tried to obey doctor’s orders and spend a good part of each day resting in bed but he couldn’t stick with it. His mind was too active, and this new research was the most exciting thing he had ever done. He worked at it as intensely as he had worked on other projects, by trial and experience. He had two-way conversations with himself, first posing a question, then exploring each possible answer until he could either validate it or eliminate it. By doing this, he made his first big breakthrough; got the first real answer. It was about a month after he’d begun his self-search, and he was looking into the question of happiness. He’d already eliminated some answers and once again asked himself, “What is happiness?” The answer that came this time was, “Happiness is when you’re being loved.” That seemed simple enough. He went on. “Okay, would you say you are happy now? Do you feel happy?” The answer was no. “Okay,” was the conclusion, “then that must mean you are not loved!” “Well, that’s not exactly true,” came the rebuttal. “Your family loves you.” That made him stop and think. He saw again their concerned faces when he’d been so sick in the hospital, remembered the pleasure in their eyes when he’d returned home after each lengthy sojourn elsewhere, heard his sister Doris’ sweet voice on the telephone, “How are you, honey?” Oh, yes, he was loved. There was no mistake about that. And there were women, too. He could think of more than one who would marry him in a minute if he asked. He knew it was so because they had asked him, and had broken off the relationship when he refused. There were men who loved him, too, as a friend. These were men he had known all his life, real friends who had stood by him through all kinds of difficulties, who still called regularly just to say hello and see how he was doing, who enjoyed spending time with him. They loved him. It came as a shock that with all that love, he still wasn’t happy. It became obvious that being loved was not the answer to happiness. He threw it out and tried a new approach. “Maybe happiness lies in accomplishments,” he thought. He remembered when he’d won the Rutgers scholarship, when Kelivinator had upped his salary, when he got his first apartment, when he opened the first Hitching Post, when he made the coup in Canadian lumber. Proud of himself, yes. But happy? No, not what he would call happy. “Well, then,” he asked himself, “have I ever been happy and if so, when?” The first part was easy; of course, he’d been happy sometimes. But when, specifically? He began to look at it… there were the summer times years ago when he was camping out with the fellows. He had been happy then. Oh, not every minute, of course, so what were the specific moments? The first thing that flashed into his mind was a picture of him helping his friend, Sy, put up his tent one summer. Sy had arrived late in the afternoon and one of his tent ropes had broken. Lester had helped him, both of them laughing, pleased with their friendship, feeling good about themselves and each other. He had been happy then. He chuckled at the memory. He felt good even now, thinking about it. “What were some other times?” he asked, and the next thing he remembered was how he felt when his friend, Milton, had eloped in college. No one was supposed to know about it, but Milton had told his best friend, Lester. He had been very happy then; was it because he felt special that Milton had told him a secret? Upon reflection he saw that it wasn’t that. No, it was the expression on Milton’s face, talking about his beautiful new bride and how much he loved her; they just didn’t want to wait until after college. Lester had felt a twinge of envy for a moment, but then had looked closely at his friend’s face beaming with love and he knew he had definitely been happy for Milton. He felt the happiness well up in him even now, after all the years, as he sat with eyes closed, reviewing the scene in his mind. Yes, he had been happy then. As he continued to review the past, happy times came faster and faster. He remembered June and driving to pick her up for a date, his heart singing with love, impatient to see her. He had been happy then. And there was Nettie. Oh, God, he hadn’t thought about her for such a long time. He really didn’t want to now, there was so much pain attached to it, but there it was. He’d been running away from that pain all his life it seemed, and he was tired, tired of running. It was the end of the line and he simply couldn’t run any longer. So he forced himself to look and to question. Oh, yes, he had been happy with Nettie. Memories flashed through his mind, moments when he had held her in his arms so tenderly wanting to take her right inside himself. Moments at parties, when he would unexpectedly catch her eye across a room and be flooded with love. Remembering her smile, the sun glinting on her hair, the serious look on her face as they sat studying together, the faint flowery smell of her, the sound of her laughter, her voice soft in the night, “I love you, Lester.” He sat back and let the pictures flood him, wash over him, let it all flow, let the longheld pain flow. His heart ached until his carefully erected, protected dam broke and for the first time, he cried over his lost love, his Nettie, his darling. Grief seemed to come from some bottomless pit of pain and loneliness. It went on for what seemed like hours and when it was over, he felt drained and weak. When he could, he crept from the chair to his bed and slept like a dead man.

What Is happiness?

前の内容:

ミラーニューロン - 考えかたは100%他人の影響 - 01

(2015-02-22 07:07:18 | 心を掘り下げる(内観))

マイナスのミラーニューロンの影響をなくして、

ポジティブなミラーニューロンの影響を増やす。

長期的に総合的にみて、幸せな人をメンターに選ぶ。

どうすれば、さらにこの人たち(メンター)に提供できるかと考える。

以心伝心(天網恢々疎にして漏らさず)

良いものを取り入れることに集中する。

尊敬できる人と一秒でも多くいるように考える。

一人一人を大事にする。

ポジティブなミラーニューロンの人を増やしていく。

長期的に総合的にみて、誰かを幸せにすると、幸せの連鎖が広がる。

ポジティブな環境(個人・グループ)を自分でつくる。

参考サイト:

誰かと同じ現実を持つと、その人と同じ結果を持つことになる。

(2015-02-26 21:58:30 | 心を掘り下げる(内観))

六つのステップ

六つのステップは、セドナメソッドのエッセンスの精髄です。1974年にレスター・レヴェンソンが、解放の全手順を要約するために作りました。

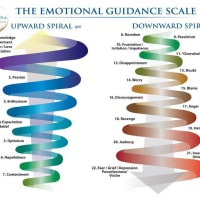

- 承認や制御、安全や分離/一体を求める以上に、自由/不動心を求めます。

- 解放して、自由/不動心を得ることができると心に決めます。

- すべての感情は四つの欲求(承認、制御、安全、分離/一体)から発生していることを認識します。そして、それらの欲求を手放します。

- 常時、解放します。一人でいるときも、誰かと一緒にいるときも、四つの欲求を常に解放します。

- 行き詰まったら、行き詰まった状態を制御したり変えたりしたい気持ちを手放します。

- 解放する度に、より軽く、幸せで、有能だと感じます。開放を続ければ、常にその状態になります。

-----

根本の、一番最初の制限は以下の通りです:

「私はすべてから、分離した個人です。」

それを除去してください。そうすれば、制限、すべての問題、

すべての病気、すべての欠乏をすべて除去します。

The action required to go free is releasing all the obstruction.

自由になることを要求される行動は、すべての障害をリリースしています。

(自由に行くために必要な行動により、すべての障害はリリースされている。)

-----

例:

-----

私が変えたいことは、何ですか?

変えたいことを、書き出します。

(書き出した一つごとに、以下の質問をして手放します。)

例:「私はすべてから、分離した個人です。」

私はそれを変えたいという気持ちを受け入れますか? 「はい」

(認めて受け入れます。受け入れると決めます。)

私はそれを変えたい気持ちを手放しますか? 「はい」

私は自分自身ができるだけそうであるものを受け入れることを許しますか? 「はい」

(私は自分自身がそれを受け入れることを許しますか? 「はい」)

私は自分自身がそれを手放すことを許しますか? 「はい」

六つのステップ

Lester Levenson - the true story (英語です。)

http://www.presentlove.com/lester-levenson/

Lester Levenson’s story

In the hospital.

Lester Levenson

At the end of two weeks, Dr. Schultz arrived for his regular morning visit, and after examining his patient, pulled up a chair and sat down. “I’m discharging you today. Your condition is stable, and there’s no reason to keep you here any longer. Now that doesn’t mean you’re well. Far from it. You need an indefinite period of convalescence as well as checkups at regular intervals. But you don’t need to be in the hospital any longer. You can continue with bed rest and medication at home.” The doctor went on to outline his at-home program of rest, medication, and regular office visits; his diet; social activities (none); even his sex life (also none). Lester was surprised, but determined to follow doctor’s orders. “How long will this go on, Doc?” he asked. “How long do I have to take it easy like this? I realize you can’t tell me exactly, but can you give me some idea?” He watched the doctor carefully as he waited for an answer. It seemed like a long time before Dr. Schultz spoke. “How old are you, son?” That wasn’t what he expected. He wondered what was coming next. There was something in the doctor’s manner he didn’t like. “Forty-two,” he answered and waited. Dr. Schultz looked out the window, his face impassive as he sat lost in thought. After a long moment, during which neither man moved, the doctor nodded his head once, a sharp decisive movement which frightened Lester, and spoke abruptly and with finality. “From now on, I’m afraid.”

“What do you mean, from now on?” A very sick feeling was rising from his gut, up into his stomach. “I mean that you cannot expect to live a normal life from here on.” He went on quickly when he saw Lester’s shocked look. “You’ve just had a very serious coronary; you’re lucky to be alive at all. Anyone else would have been dead by now with the severity of this attack.” The doctor paused, then cleared his throat, “I realize how difficult it must be for you to hear this, but I assure you it isn’t pleasant for me either.” He got up abruptly and walked to the window, his back to Lester. “I wish there were something else I could say; I wish I could tell you that in a few months you’d be back to normal and could pick up your life where you left off,” he paused, turning to face Lester quietly, “but I can’t. In all conscience, I can’t tell you that And I’m sorry.” Lester was angry now. “You’re sorry? Well, so am I! You saved my life … for what? So that I can be an invalid for the rest of it? What the hell kind of life are you giving me back anyway?” Once started, he couldn’t stop. He raved on and on. All his frustration, rage and anger poured out until the sick feeling in the pit of his stomach finally rose to his throat and he began to cough and choke. The doctor held a basin for him while he gagged and heaved and finally fell back exhausted onto the pillows, his hand shaking as he reached up to wipe his mouth. The doctor was shaking too as he carried the soiled basin to the bathroom. He carefully placed it on the floor, then hunched over the sink, one hand on each side of it supporting his weight, his forehead touching the cold mirror of the medicine chest on the wall. In spite of all his years of practice, these situations still affected him. He thought of home and wished he were there now, his day over, relaxing before dinner with a drink or two. With a deep sigh, he pulled himself erect and walked back into the room. “I’ll sign the discharge papers today. but you can stay on if you want,” he said quietly “If you need more time to make your arrangements, I’ll tell the nurse it’s okay.” He didn’t know what else to say. Lester answered, “No, that’s all right, I’ll leave today, this afternoon. There doesn’t seem to be any point in prolonging it” “All right, whatever you decide is all right. But remember that you can change your mind and stay a bit longer if you want.” He stood in silence for a moment, while he closely examined Lester’s ashen face. “Please be sure to take it easy when you get home. I can’t overemphasize the importance of that. You shouldn’t climb any stairs at all. And do you have shoes without laces; you know, loafers?” “Loafers? No, why?” “You might want to have someone buy you a pair. It’s better if you don’t have to bend over to tie your shoes. It puts an additional strain on your heart when you get into that position.” The idea struck Lester as ridiculous but all he said was “Okay, whatever you say.” He’d always hated loafers but it didn’t matter now. Then as he watched the doctor walk toward the door, a question occurred to him. “Doc,” he asked, “I’m not going to die, am I? I mean, I might have to kind of take it easy from here on, but I’m not going to die, right?” Dr. Schultz stopped. “I don’t know,” he answered, then turned to face Lester. “I wish I could give you a positive answer, but I can’t. The truth is that I simply don’t know. You’ve had a massive heart attack and you could live for another year or two, or you could go tomorrow. I just don’t know.” “Thanks for being honest with me, Doc. I’ll be seeing you.”

Lester goes home.

That afternoon, he went home to his penthouse as though to a tomb. “It is a tomb,” he thought, “and I’m a dead man. I guess I’ll just have to get used to it.” His sisters wanted to help and offered to take turns staying with him, to take care of him, but he sent them away. He just wanted to be by himself. He went to bed and mostly slept for three days, waking up only occasionally to eat, or take his medicines, or use the bathroom. Then he’d crawl, like a wounded animal, back to his hole. On the fourth day something changed. After his midday meal he was sitting in a chair, looking out the window at Central Park. There was snow; the trees were sparkling; the park looked like a fairyland. He was thinking of how beautiful it was and then realized that he wasn’t enjoying it at all. He could not respond, even to beauty. He was a virtual invalid, with no hope of ever getting any better. At best, he could look forward to years of sitting in this apartment, nursing a frail corpse that hadn’t the good sense to lie down and get it over with. That thought made him so furious he got up from his chair with the greatest surge of energy he’d had since his attack, went straight to the medicine chest in the bathroom and counted his pills. He found a good supply of the newer medications; sedatives and heart pills. There were also morphine tablets a doctor had prescribed some years before for the pain of kidney stones. There were certainly enough left in the bottle to take him off this planet if he chose to go. And morphine would be such a nice way to go; you just floated off on a warm, cozy cloud, everything rosy. It was certainly better than waiting for another heart attack. Okay. Now he had a choice. For the first time since his illness, he felt he had some control over what happened to him. He considered what to do. Should he take the pills now and get it over with? No, not right now he decided; he could always take them when and if things got too bad. He went back to his chair and began looking the situation over, speaking aloud to himself, “You’re still breathing. No matter what those doctors or anyone else says about the prognosis, you’re still breathing, and that’s what counts. Maybe there’s some hope after all.” “Okay, where do I start?” That question brought on the sinking feeling again, and it occurred to him that perhaps he should go ahead and take the pills at once. At least then he’d be out of his misery and could stop fighting. And what had he been fighting for all his life anyway? Just a little happiness, that was all; and he hadn’t found it, not ever, not in any way that lasted more than a few minutes or hours at a time. Momentary… that’s what life was… momentary… impermanent… always changing… you’d no sooner think you had it made, had everything nailed down and could relax, than the next thing would happen and there you were again … right back where you’d started … clutching, clutching, clutching for something you couldn’t hold even if you got it. What the hell was life all about anyway? What was it all about? What was he doing here on this planet? It didn’t make any sense to him that he should be born; go through all he had gone through in his life; never really get anywhere that really mattered; and end up with nothing, absolutely nothing except a dying body and eventually even that turns to dust. All his possessions and accomplishments felt meaningless and empty. “Like dust,” he thought. “Ashes to ashes and dust to dust… If the war doesn’t get you, the taxes must.” He had to laugh at the truth in that silly rhyme. Life seemed so stupid. But as he thought about taking the pills, he realized that he couldn’t give up yet. There was something stirring in the back of his mind … an elusive thought that there might be an answer if only he knew where to look. Well, he had nothing but time, he figured, and even though his body was half dead, he still had his mind; he could still think. “Should I try?” he wondered aloud. For a moment, he wavered, then decided with a shrug, “Oh, what the hell … I got nothing to lose. If it doesn’t work, I can always take the pills.” And he knew he would if it came to that. There was no doubt in his mind.

That being settled, he didn’t have to think about it again. His mind felt clearer than it had in a long time, and for the first time since his illness, he felt truly hungry. He went to the kitchen and fixed himself a real meal. Still very weak, he took his time and didn’t try to rush. As he ate, his mind was busy exploring new thoughts, questions, ideas of where to look for his answer. The new project was exciting and he felt himself coming alive again. Refreshed and strengthened by the meal, he went back to his chair by the window. “Where to begin?” he wondered, “Well, first, what are the questions?” What is life? What is it all about? Is there a reason for my being here in this world, and if so, what is it?” “What is life? What is it that I’ve been looking for?” “Just a little happiness, that’s all,” he answered himself. “Okay, then, what is happiness? How do you get it? Where do you find it?” “What is life? What is this world all about and what is my relationship to it?” “How did I get into this mess I’m in?” “Is there a way out of this mess?” He already knew the answer to that one. Other than dying, there is no way out, but he thought if he could only get the answers, at least he’d know the reason for his life. He might make some sense out of it all, and that would be something. It would have to do. First, he looked in the dictionary for definitions of happiness and life. They didn’t tell him anything he didn’t already know. Next, he went to his library of books collected over the years. There was Freud; could there be anything useful in that? No, he’d tried Freudian analysis for years, and it hadn’t helped. He’d also read every book Freud had written that had been translated into English and hadn’t found the answers. No, Freud had no answers for him. He went on to others; Watson’s Behaviorism, Jung and Adler, nothing for him in those, either. Then there were the philosophers. He began taking books from the shelves, putting them in a pile. He’d read them all cover to cover more than once, but maybe he’d missed something. After all, he thought, he hadn’t then had specific questions. Taking books to his chair by the window, he began to read. He skimmed through one after the other, stopping to read paragraphs or pages here and there. His head began to feel clogged with information, and his thoughts were spinning. More and more impatient, he went back to the shelves for other books, books on medicine, physics, engineering. He had books on everything and he looked through them all over the next two days. The room was a mess, books piled everywhere, some lying open on the floor where he had thrown them in his frustration. The only ones left on the shelves were a joke book and some biographies, which had been given to him as gifts. Where to look next? “You were always a smart boy” he told himself. “Didn’t you win a full scholarship to Rutgers by competitive exams when there were only three being given? Even though you were a Jew, they couldn’t hold that back from you. You won it! “And in school, weren’t you always on the honor roll? And haven’t you read tons of stuff on man, from engineering and physics to psychiatry and philosophy and medicine? “Well, if you’re so smart, big shot, what did all that study and knowledge and reading get you? Migraines, kidney stones, ulcers, appendicitis, pain, misery, unhappiness, and finally a coronary which should have finished you off and didn’t. What more do you need before you come to your senses? “For a smart boy Lester, you are stupid, stupid, stupid! All that knowledge has availed you nothing. And here you are looking for more, wanting more books written by someone else who hasn’t found the answers either.” “That’s that!” he told himself. “I’m finished with all that crap.” With that decision, he felt a lifetime burden lift from his shoulders. Suddenly he felt light, almost giddy. He realized he had actually been looking for the same answers all his life, but now he knew, without a doubt, that if they were to be found in any of the conventional places, he would have already found them. He would have to look somewhere else. And he thought he knew where. He would put all that useless knowledge aside, disregard everything he’d learned, go back to the lab and start from scratch. The problems were within him, he reasoned. It was his body, his mind, his emotions. The answers must be within him, too. That was his lab and that’s where he would look. It felt good. He went to his chair and began.

Answers begin to emerge.

For a month he sat, relentlessly questioning, probing. At first, he tried to obey doctor’s orders and spend a good part of each day resting in bed but he couldn’t stick with it. His mind was too active, and this new research was the most exciting thing he had ever done. He worked at it as intensely as he had worked on other projects, by trial and experience. He had two-way conversations with himself, first posing a question, then exploring each possible answer until he could either validate it or eliminate it. By doing this, he made his first big breakthrough; got the first real answer. It was about a month after he’d begun his self-search, and he was looking into the question of happiness. He’d already eliminated some answers and once again asked himself, “What is happiness?” The answer that came this time was, “Happiness is when you’re being loved.” That seemed simple enough. He went on. “Okay, would you say you are happy now? Do you feel happy?” The answer was no. “Okay,” was the conclusion, “then that must mean you are not loved!” “Well, that’s not exactly true,” came the rebuttal. “Your family loves you.” That made him stop and think. He saw again their concerned faces when he’d been so sick in the hospital, remembered the pleasure in their eyes when he’d returned home after each lengthy sojourn elsewhere, heard his sister Doris’ sweet voice on the telephone, “How are you, honey?” Oh, yes, he was loved. There was no mistake about that. And there were women, too. He could think of more than one who would marry him in a minute if he asked. He knew it was so because they had asked him, and had broken off the relationship when he refused. There were men who loved him, too, as a friend. These were men he had known all his life, real friends who had stood by him through all kinds of difficulties, who still called regularly just to say hello and see how he was doing, who enjoyed spending time with him. They loved him. It came as a shock that with all that love, he still wasn’t happy. It became obvious that being loved was not the answer to happiness. He threw it out and tried a new approach. “Maybe happiness lies in accomplishments,” he thought. He remembered when he’d won the Rutgers scholarship, when Kelivinator had upped his salary, when he got his first apartment, when he opened the first Hitching Post, when he made the coup in Canadian lumber. Proud of himself, yes. But happy? No, not what he would call happy. “Well, then,” he asked himself, “have I ever been happy and if so, when?” The first part was easy; of course, he’d been happy sometimes. But when, specifically? He began to look at it… there were the summer times years ago when he was camping out with the fellows. He had been happy then. Oh, not every minute, of course, so what were the specific moments? The first thing that flashed into his mind was a picture of him helping his friend, Sy, put up his tent one summer. Sy had arrived late in the afternoon and one of his tent ropes had broken. Lester had helped him, both of them laughing, pleased with their friendship, feeling good about themselves and each other. He had been happy then. He chuckled at the memory. He felt good even now, thinking about it. “What were some other times?” he asked, and the next thing he remembered was how he felt when his friend, Milton, had eloped in college. No one was supposed to know about it, but Milton had told his best friend, Lester. He had been very happy then; was it because he felt special that Milton had told him a secret? Upon reflection he saw that it wasn’t that. No, it was the expression on Milton’s face, talking about his beautiful new bride and how much he loved her; they just didn’t want to wait until after college. Lester had felt a twinge of envy for a moment, but then had looked closely at his friend’s face beaming with love and he knew he had definitely been happy for Milton. He felt the happiness well up in him even now, after all the years, as he sat with eyes closed, reviewing the scene in his mind. Yes, he had been happy then. As he continued to review the past, happy times came faster and faster. He remembered June and driving to pick her up for a date, his heart singing with love, impatient to see her. He had been happy then. And there was Nettie. Oh, God, he hadn’t thought about her for such a long time. He really didn’t want to now, there was so much pain attached to it, but there it was. He’d been running away from that pain all his life it seemed, and he was tired, tired of running. It was the end of the line and he simply couldn’t run any longer. So he forced himself to look and to question. Oh, yes, he had been happy with Nettie. Memories flashed through his mind, moments when he had held her in his arms so tenderly wanting to take her right inside himself. Moments at parties, when he would unexpectedly catch her eye across a room and be flooded with love. Remembering her smile, the sun glinting on her hair, the serious look on her face as they sat studying together, the faint flowery smell of her, the sound of her laughter, her voice soft in the night, “I love you, Lester.” He sat back and let the pictures flood him, wash over him, let it all flow, let the longheld pain flow. His heart ached until his carefully erected, protected dam broke and for the first time, he cried over his lost love, his Nettie, his darling. Grief seemed to come from some bottomless pit of pain and loneliness. It went on for what seemed like hours and when it was over, he felt drained and weak. When he could, he crept from the chair to his bed and slept like a dead man.

What Is happiness?