"しかし、錬金術師は、少なくとも間接的にそれを感じ取っていました。錬金術師は、全体の一部として、自分の中に全体のイメージ、パラケルススが言うところの「天空」または「オリンパス」があることを確実に知っていました。この内部の小宇宙は、知らず知らずのうちに錬金術の研究対象となっていたのです。

今日、私たちはそれを集合的無意識と呼んでいますが、それを客観的と表現するのは、それがすべての個人において同一であり、したがって「一つ」であるからです。

この普遍的なものから、各個人に主観的な意識、すなわち自我が生まれる。

これは大まかに言えば、今日の私たちがドーンの「かつての1つ」と「神の創造行為によって分離された」を理解する方法である。

このような自己に関する客観的な知識は、著者が言う「自分が誰であるかではなく、何であるか、何に依存しているか、誰のものか、何のために作られたかを知らなければ、誰も自分を知ることはできない」という意味である。

'Nemo vero potest cognoscere se, nisi sciat quid, et non quis ipse sit, a quo dependeat, vel cuius sit ... et in quem finem factus sit.".

"quis」と「quid」の区別は非常に重要である。「quis」は紛れもなく個人的な側面を持ち、自我を指しているのに対し、「quid」は中性であり、人格さえ与えられていない対象物以外には何も述語しない。精神の主観的な自我意識ではなく、いまだに調査されなければならない未知の、偏見のない対象としての精神そのものを意味している。自我の知識と自己の知識の違いは、この「quis」と「quid」の区別の中で、これ以上ないほど明確に定式化されています。

16世紀の錬金術師は、ある心理学者(あるいは心理学的な問題で自分の意見を述べることを認めている人たち)が今日もなお躓いている何かを、ここで指差しているのである。"自我は一方で因果的にそれに「依存」または「属する」ものであり、他方で目標のようにそれに向かっているので、「何」は中立的な自己、全体の客観的な事実を指しているのです。これは、イグナチオ・ロヨラの『ファウンデーション』の印象的な冒頭文を思い起こさせる。

Exercitia spiritualia, "Principio y Fundamento":

"Homo creatus est (ad hunc finem), ut laudet Deum Dominem nostrum, ei reverentiam exhibeat, eique serviat, et per haec salvet animam suam."

"人間は我々の主である神を讃え、敬い、仕え、それによって自分の魂を救うために創られた。"

人間は、自分の身体の生理学についてごく限られた知識しか持っていないのと同様に、自分の精神のごく一部しか知らない。

人間の精神的存在を決定する因果関係は、その大部分が意識の外にある無意識のプロセスに存在しており、同じように、人間の中には、同様に無意識に由来する最終的な要因が働いている。

フロイトの心理学は原因的要因を、アドラーの心理学は最終的要因を初歩的に証明している。原因と結果は、過小評価されてはならない程度に意識を超えており、このことは、意識の対象とならない限り、その性質と作用は変えられず、不可逆的であることを意味している。意識的な洞察と道徳的判断によってのみ修正されるのであり、だからこそ自己認識が必要とされ、恐れられているのである。

したがって、「Foundation」の冒頭の文章から神学的な用語を取り除くと、次のようになる。

"人間の意識は、(1)高次の統一体(Deum)からの降臨を認識し(laudet)、(2)この源に十分かつ慎重に敬意を払い(reverentiam exhibeat)、(3)その命令を知的かつ責任を持って実行し(serviat)、(4)それによって精神全体に最適な生命と発展を与える(salvet animam suam)ために創造された」。

この言い換えは、合理主義的に聞こえるだけでなく、そうであることを意味しています。なぜなら、あらゆる努力にもかかわらず、現代人の心は、2000年前の神学的な言葉を、「理性と一致する」場合を除いては、もはや理解できないからです。

その結果、理解の欠如がリップサービスや気取った態度、強制的な信念、さもなければ諦めや無関心に取って代わられてしまうという危険性は、とっくに実現しているのである。"

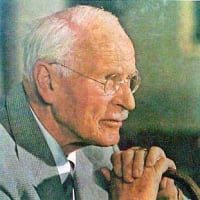

- カール・グスタフ・ユング『アイオン』P.164-165、par. 251-254

アートワーク|Tomasz Alen Kopera

“The alchemist, however, had at the very least an indirect inkling of it: He knew definitely that as a part of the whole he had an image of the whole in himself, the “firmament” or “Olympus”, as Paracelsus calls it. This interior microcosm was the unwitting object of alchemical research.

Today we would call it the collective unconscious, and we would describe it as objective because it is identical in all individuals and is therefore ‘one’.

Out of this universal one there is produced in every individual a subjective consciousness, i.e., the ego.

This is, roughly, how we today would understand Dorn’s “formerly one” and “separated by divine act of creation”.

This objective knowledge of the self is what the author means when he says: ‘No one can know himself unless he knows what, and not who, he is, on what he depends, or whose he is, [or: to whom he belongs] and for what end he was made.

‘Nemo vero potest cognoscere se, nisi sciat quid, et non quis ipse sit, a quo dependeat, vel cuius sit ... et in quem finem factus sit.”

“The distinction between ‘quis’ and ‘quid’ is crucial: whereas ‘quis’ has an unmistakably personal aspect and refers to the ego, ‘quid’ is neuter, predicating nothing except an object which is not endowed even with personality. Not the subjective ego-consciousness of the psyche is meant, but the psyche itself as the unknown, unprejudiced object that still has to be investigated. The difference between knowledge of the ego and knowledge of the self could hardly be formulated more trenchantly then in this distinction between ‘quis’ and ‘quid’.

An alchemist of the 16th century has here put his finger on something that certain psychologists (or those of them who allow themselves an opinion in psychological matters) still stumble over today. “What” refers to the neutral self, the objective fact of totality, since the ego is on the one hand causally ‘dependent on’ or ‘belongs to’ it, and on the other hand is directed towards it as to a goal. This recalls the impressive opening sentence of Ignatius Loyola’s ‘Foundation’:

Exercitia spiritualia, “Principio y Fundamento”:

“Homo creatus est (ad hunc finem), ut laudet Deum Dominem nostrum, ei reverentiam exhibeat, eique serviat, et per haec salvet animam suam.”

“Man was created to praise, do reverence to, and serve God our Lord, and thereby to save his soul.”

Man knows only a small part of his psyche, just as he has only a very limited knowledge of the physiology of his body.

The causal factors determining his psychic existence reside largely in unconscious processes outside consciousness, and in the same way there are final factors at work in him which likewise originate in the unconscious.

Freud’s psychology gives elementary proof of the causal factors, Adler’s of the final ones. Causes and ends thus transcend consciousness to a degree that ought not to be underestimated, and this implies that their nature and action are unalterable and irreversible so long as they have not become objects of consciousness. They can only be corrected through conscious insight and moral determination, which is why self-knowledge, being so necessary, is feared so much.

Accordingly, if we divest the opening sentence of the “Foundation” of its theological terminology, it would run as follows:

“Man’s consciousness was created to the end that it may (1) recognize (laudet) its descent from a higher unity (Deum); (2) pay due and careful regard to this source (reverentiam exhibeat); (3) execute its commands intelligently and responsibly (serviat); and (4) thereby afford the psyche as a whole the optimum degree of life and development (salvet animam suam).”

This paraphrase not only sounds rationalistic but is meant to be so, for despite every effort the modern mind no longer understands our 2000-year-old theological language unless it ‘accords with reason.’

The result, the danger that lack of understanding will be replaced by lip-service, affectation and forced belief, or else by resignation and indifference has long since come to pass.”

— Carl Gustav Jung, Aion, P. 164-165, par. 251-254

Artwork | Tomasz Alen Kopera