Photo Tech Complicates Child-Porn Cases

Each week, about 100,000 sexually explicit images of children arrive on CDs or portable disk drives at Michelle Collins' office.

They are sent by police and prosecutors who hope Collins and her 11 analysts at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children can verify that the graphic pictures are real, not computer-generated. When they can't, officials sometimes turn to outside experts.

All this is being done - at an annual cost in the millions of dollars collectively in child-pornography cases alone - as software like Photoshop makes it easier to fake photos and as juries become more skeptical about what they see.

Although challenges to digital photos come in all types of criminal and civil cases, they are especially pronounced in child-pornography cases because of a 2002 U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down a ban on computer-generated child pornography. Defense attorneys are trying to use the ruling to introduce reasonable doubt in jurors' minds about the images' authenticity.

Prosecutors still generally prevail, but "this has certainly created an additional burden," said Thomas Kerle of the Massachusetts State Police. "I can say that unequivocally, it has made the prosecution of these types of cases more difficult. It takes ... resources I think could be better applied to investigating" more cases.

Drew Oosterbaan, who heads the U.S. Department of Justice's Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section, said prosecutors sometimes submit only photos they can easily verify because outside experts can be expensive - with travel, hotels and consulting fees, along with possible delays.

"This can affect the sentence the defendant gets," he said. "Before (the 2002 ruling) we would generally charge all the images."

Oosterbaan added that although defense lawyers have the right - and duty - to challenge evidence, they are doing so without "any shred of evidence there are wholly computer-generated images being generally circulated and passed off as real children out there."

And many law-enforcement officials worry that the time and money needed to withstand any challenges will only grow as technology improves and makes it more difficult to tell a computer-generated image from a real one.

"I feel that pretty much we can tell the difference right now," said Karl Youngblood of the Alabama Bureau of Investigation. "How much longer that's going to last, I don't know with the technology going at the rate it's going."

Of course, there's a cost to defendants as well - sometimes more so because federal law limits where and when the defense may review images to restrict their distribution, meaning experts must often travel with expensive equipment to a police lab in another city.

"If something becomes more difficult for the government to prove, so be it. They have the burden of proof," said First Amendment lawyer Louis Sirkin, lead counsel in the challenge that led to the 2002 Supreme Court ruling.

Child pornography is illegal in the United States, but the Supreme Court in 2002 struck down on free-speech grounds a 1996 federal ban on material that "appears to be" a child in a sexually explicit situation. That ruling covers computer-generated images, though morphing - such as the grafting of a child's school picture onto a naked body - remains illegal.

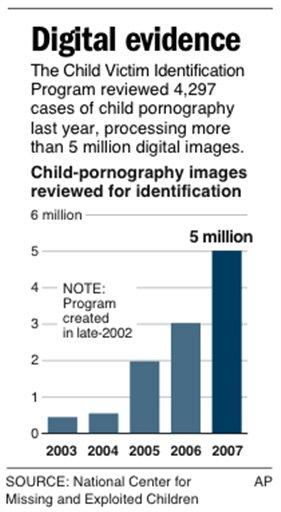

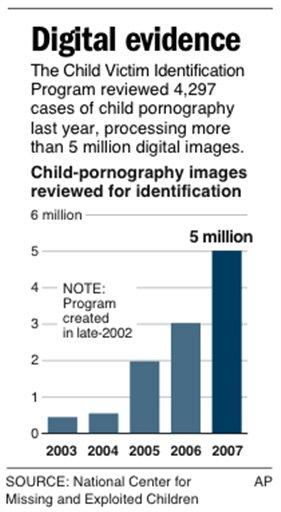

Collins' Child Victim Identification Program in Alexandria, Va., grew out of that ruling. After officials submit seized photos, the center uses software and visual inspections to look for matches. It can usually verify that children in some or all of the images are known and real.

The program, which costs about $1 million a year to run, now has about 1,300 children in its database, up from 20 in 2002. Staff grew from just Collins then to 11 full-time analysts who now work under her. The program reviewed 5 million images last year, up from about 450,000 in 2003, the program's first full year.

Because of the graphic nature of the images, a psychologist visits each week, and analysts must undergo counseling at least quarterly.

"Not everybody can do it," said Raymond Smith, a longtime investigator who oversees child-exploitation cases at the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. "You have to be able to come to grips with seeing children be victimized and abused. It can tear you up, (but) through your efforts you are identifying the people that hurt these children."

When the center cannot make a match, prosecutors can turn to outside experts. Sometimes, it's a pediatrician who can say a real child has characteristics matching those seen in the photo. Other times it's a computer expert who can talk about how difficult it is to produce images and video of that quality.

Hany Farid, a Dartmouth College professor who has testified for the prosecution in some cases, said he has been getting more inquiries about authenticity - not only for child-pornography cases but also civil lawsuits questioning medical images in malpractice cases or signatures in contract disputes. News organizations have also looking for ways to authenticate photos.

"Because so many people get photographic fakes in their (electronic) mailboxes, to the average juror it resonates," he said.

The challenges can be costly, even if a case never goes to trial - the majority end in plea agreements.

Farid said he charges up to $25,000 a year for software he produced to look for signs of tampering, such as inconsistencies in shadows. He also charges as much as tens of thousands of dollars to work on a case.

Even when there is a match and an expert isn't needed, a prosecutor must seek out the detective who initially identified a child for the center. That detective must often be flown in and be ready to testify if the defense raises a challenge. In one case in Portland, Maine, a Russian detective couldn't be reached, so the prosecutor had to spend $5,000 on an expert anyway. Trials get postponed if a key witness has a scheduling conflict.

Sam Guiberson, a defense attorney who specializes in technology and digital evidence, said challenges to evidence are to be expected, digital or not.

"Every good trial lawyer is always going to subject every part of his adversary's exhibits to that sort of scrutiny," Guiberson said.

Kebin Haller, deputy director of the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation, said that in most cases, a large quantity of images are seized such that enough hold up.

How much proof a prosecutor needs in child-pornography cases can vary from region to region and even from judge to judge. Recent federal appellate rulings have eased the burden on prosecutors, essentially saying that in lieu of definitive evidence, they can let jurors make up their own minds about whether an image is real or computer-generated.

Many prosecutors, though, don't want to take that chance and would rather submit proof.

"It's difficult to prove these are real children," said Mary Leary, a Catholic University law professor who previously worked on child-abuse and child-pornography cases. "Is the defense exploiting this? Absolutely they are."

Each week, about 100,000 sexually explicit images of children arrive on CDs or portable disk drives at Michelle Collins' office.

Each week, about 100,000 sexually explicit images of children arrive on CDs or portable disk drives at Michelle Collins' office.